“Grandfathered seawall! … Motivated seller!” a December 2018 sales pitch for the property at 59-175C Ke Nui Road on Oʻahu’s famed Sunset Beach proclaimed.

Motivated, indeed.

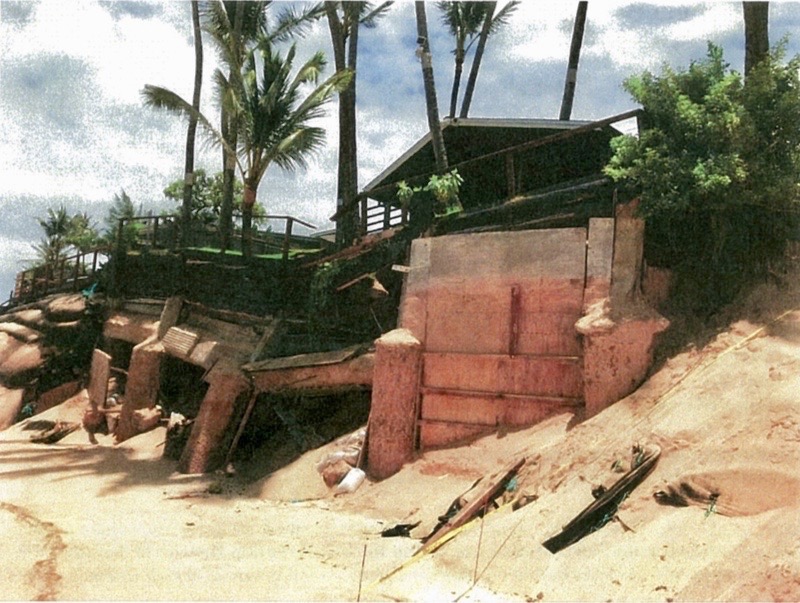

Within three months, the owner sold the lot for about half a million dollars less than the $2.4 million list price. And about a year and a half later, that “grandfathered” seawall — illegally built and on state land, according to officials — buckled after a summer hurricane swell. Further failure threatened not only the home that lay a mere 10 feet inland, but also anyone traversing the beach fronting it.

When a city excavator operator determined that there was not enough sand fronting the property to push into a protective berm, the new owners, Brandee and Liam McNamara, had an estimated 12 cubic yards of concrete poured to prop up and secure the portions of the seawall that had failed.

“What I did was support and keep this existing wall from crumbling and falling. It was a safety issue. There are so many kids in our neighborhood,” Liam McNamara explained. With a public right-of-way running alongside the lot, there is a ton of foot traffic in the area, he added.

The work was done in the state Conservation District without authorization and not long after the McNamaras had been ordered by the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands (OCCL) to remove an illegally constructed walkway and stairs in front of the seawall.

So on January 22, the OCCL recommended that the Board of Land and Natural Resources impose a $35,000 fine and require the seawall’s removal.

After a lengthy discussion, the board voted 5-2 to require the McNamaras to pay a fine of just $5,000 to cover administrative costs, and allow the remaining $30,000 fine to go toward removal expenses, rather than to the state.

OCCL administrator Sam Lemmo had explained that there was no way the concrete could be jackhammered out without destabilizing the wall. “It’s on state land. It was always on state land in my opinion. The only solution would be to demo the entire thing and give them a permit for a big burrito system,” he added.

While he said such systems are expensive to maintain, he added that allowing the McNamaras and the handful of homeowners surrounding them to harden the shoreline would exacerbate erosion of a beach that was too valuable to lose.

“This little area with five seawalls, it’s going to turn into a little peninsula as the shore erodes around it,” Lemmo said.

The McNamaras requested a contested case hearing after the board’s vote, but it was unclear by press time whether they had followed up with the required written petition.

Before the vote, board members recognized the quandary the homeowners in the area are in. The McNamaras’ lot is one of a number of houselots along the beach that have suffered severe erosion for years. The owners have at times received permission from OCCL to push sand to create a protective berm fronting their properties. Some have been allowed to install temporary sand burritos. Others, like the McNamaras, have been subject to enforcement actions for installing protective structures or doing significant seawall repairs without authorization.

“There’s no question that this is a very difficult situation and I do not think there is a solution that will make the homeowners on this area of Sunset Beach happy. The homes are built on a sand dune that nature wants to take away,” said board member Chris Yuen.

“They can go to the Legislature and ask for some financial relief or some financial assistance. … The only thing that is going to stop the shore from continually eroding is a continuous seawall along the whole length and that’s what you’re going to have instead of Sunset Beach,” he continued.

Board chair Suzanne Case shared Yuen’s view. “Unfortunately, the writing is on the wall here. … This is a difficult situation and you’re in the middle of it. The medium- and long-term situation is it gets worse and not better, from the standpoint of houses on the beach,” she told the couple.

Back to Burritos

The irony of the board’s decision is that it sets the McNamaras up to install a burrito system, which is what they wanted to protect their wall.

Liam McNamara said that the home’s previous owner had a burrito protecting it, but they had to take it out before the property could be sold (likely because it was unauthorized). And because his neighbors on both sides had them, he argued that their systems caused flanking at the beach fronting his house. Flanking happens when a shoreline structure — soft or hard — causes the land or beach at the ends of it to erode.

“Houses to the left and right [have] massive amounts of burritos. … Those definitely compromised my house,” he said, adding, “There is illegal activity with burritos.”

In 2019, Environment Hawaiʻi reported on one of those neighbors, Gary and Cynthia Stanley, who were fined for installing burritos on the beach without permission from OCCL. They sold their property in January for half a million dollars less than what they bought it for in 2018.

According to McNamara, the new owners of the property on his right added several more burritos, all the way to the ocean.

He suggested that, given the flanking that can occur with burritos, when the OCCL gives a permit to a property owner for them, the adjacent owner should automatically be allowed to install their own.

Lemmo pointed out, “The people to your right, they’re in violation.”

Even so, McNamara argued that he should have been given an opportunity to have a burrito. “Our seawall would have been safe,” he said.

That may or may not be true, as the enforcement case involving Ke Nui Road resident Rodney Youman illustrated.

At the same Land Board meeting, Youman faced significant fines for work along the shoreline to protect his house. He testified that his burrito system, which the OCCL approved in 2018, saved his house at least three times, but ultimately failed after the same hurricane swells that damaged the McNamaras’ wall.

The waves tore out a palm tree in his yard, leaving a gaping hole, so in August, he filled it with rocks and covered them with soil, Youman explained. The swells continued into December and “caused the bottom burritos to collapse and empty out completely and the top burritos collapsed, as well. The very top burrito dragged down my property and the rocks,” he said.

OCCL staff first noticed the rocks during an inspection last September and determined that they constituted a revetment on state land. The office also noted in December work being done to bury the fallen rocks with sand and install a new burrito system, without the OCCL’s authorization.

At the Land Board’s January 22 meeting, the OCCL recommended imposing a $32,000 fine for an unauthorized rock revetment and continued work after receiving a violation notice.

Youman argued that he never committed a violation, as he only placed the rocks on his property, not on state land. He also noted that last month he and his neighbor hired a contractor to excavate the fallen rocks off the beach.

“It’s been terrible. I purchased this property in 2016 and I was warned about the erosion. The first summer, basically nothing happened. But in the last three years, it’s been exponentially worse. It’s been catastrophic, especially in the last year. It’s costed me hundreds of thousands of dollars to try and save my property. It reached a point where it was inches from the front of my house. I had a literal precipice, a drop of 20 feet, a couple months ago to the point where I had to literally move my house back and up. Between that and the burrito system, it’s costed me $300,000. … It’s been devastating to me financially,” he said.

The Land Board ultimately chose to defer action in Youman’s case to give OCCL staff time to confirm whether or not all of the fallen rocks had been removed and to determine whether it should pursue a violation case for the new burrito system. Youman admitted that some of the smaller rocks might be buried under the sand, but said he would work to remove what he could as soon as possible.

Youman argued that the old burritos had been torn apart and were merely replaced. But Lemmo stressed that even so, his office needs to be kept in the loop to ensure that what’s being put in is consistent with what had been previously approved.

“This is the problem up there. We give someone an authorization, and then they way over-build things. They add to it. As Mr. McNamara reminded us about his neighbor, he built a gigantic burrito system. We never authorized that. … We have unlicensed contractors doing this in many cases. It’s a real sort of rogue situation with respect to the construction of these systems. I’m sorry if the people that you’re working with are telling you things. Generally, when I hear about it, I don’t seem to be able to verify that what they’ve told you was the truth. I just have a hard time just keeping up with what’s going on up there. We all do,” Lemmo said.

Disclosure

In some violation cases, oceanfront property owners know that the state or county would likely require a permit, but nonetheless proceed with installing protection measures without any authorization. Molokaʻi resident George Peabody is one such owner. On more than one occasion he has characterized the state’s efforts to prevent shoreline hardening as the work of “fascist stooges.” At the Land Board’s January 22 meeting, he and his wife, Susan, were fined $80,000 for constructing a low, rock and concrete wall in the Conservation District and on state submerged land fronting their Kaunakakai home.

But in other cases — including Youman’s, the McNamaras’, the Stanleys’ — the owners appear to want to comply with laws, but seem to have either been misled or lacked clarity regarding what they are and aren’t allowed to do to protect their homes and/or shoreline structures.

The Stanleys said they were told by a contractor that they had a permit to install additional sand burritos when they didn’t. Youman believed he could replace shredded burritos without needing OCCL approval. And the McNamaras were led by real estate agents and the previous property owner to believe that their seawall was legal and could be repaired as long as at least half of it was still intact.

All bought their Sunset Beach homes in recent years and knew of the erosion threats they faced beforehand. But all of them eventually wound up in front of the Land Board facing fines for unauthorized shoreline work.

In discussing the McNamara case, board member Sam Gon noted that with climate change expected to cause sea level to rise, “it is an era where oceanfront property is no longer a benefit, but a major liability. … [Buyers] need to be better informed of what they are getting into by their Realtors and others involved in the transaction.”

In recent years, state legislators have tried and failed to pass bills that would require real estate transactions in coastal areas or areas vulnerable to sea level rise-associated hazards to include some kind of disclosure statement.

The Hawaiʻi Association of Realtors has argued that their oceanfront property disclosure forms suffice.

This year, a number of similar bills have been introduced.

Senate Bill 473 and House Bill 596 would “require that a vulnerable coastal property purchaser statement be provided as a condition of the sale or transfer of any vulnerable coastal real property to ensure that new property owners understand the risks posed by sea level rise and other special hazards, permitting requirements, and limitations that may affect vulnerable coastal property.”

Among other things, that statement would include a recognition of changes made last session to the state’s Coastal Zone Management Act that make it harder to install shoreline protection structures at sandy beaches and in areas that would result in flanking.

“Obtaining permits to repair or install shoreline protection structures may be difficult due to state and federal coastal zone management policies discouraging coastal hardening,” the draft states.

If passed as is, the bill would go into effect at the start of next year.

HB 431 and SB 292 call for something similar, a sea level rise exposure statement for “all vulnerable coastal property sales or transfers.”

Retreat Incentive

For those who already own these vulnerable coastal properties, there is House Bill 1373, which would establish a beach preservation revolving fund (paid for by 100 percent conveyance taxes collected from the sale of oceanfront property) and a pilot low-interest mortgage program to encourage owners “to relocate mauka of expected sea level rise and erosion hazard zones.” The bill would also amend coastal zone management laws to prohibit the “construction of shoreline hardening structures within the shoreline setback area, including seawalls, groins, revetments, and geotextile shore protection projects,” except in certain cases where public infrastructure is imminently threatened by coastal erosion. The bill also proposes to prohibit the alteration, repair or replacement of existing shoreline hardening structures.

— Teresa Dawson

For Further Reading

Environment Hawaiʻi has written extensively over the decades about seawalls, shoreline construction, and sea level rise. The following is a very short list of articles related to this month’s story. These and more are available on our website, www.environment-hawaii.org.

- “State Land Board Grapples with Threat of Coastal Erosion to Infrastructure, Homes,” June 2014;

- “Land Board to Legislature: Please, Consider Shoreline Easement Bills,” February 2018;

- “Bill Would Ensure Land Purchasers Know Of Sea Level Rise Threat,” March 2018;

- “Board Talk: Windward Oahu Seawalls,” November 2018;

- “City, State Planners Explore Solutions To Sea Level Rise Hazards on O’ahu,” November 2019;

- “BOARD TALK: Owners of Sunset Beach Home Contest Proposed Fine, Sand Burrito Removal,” and “City Climate Change Commission Mulls Changes to Shoreline Setback Ordinance,” December 2019.

Leave a Reply