During the evidentiary portion of the contested case hearing for the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), parties to the proceeding would often attempt to cast doubt on the credibility of witnesses. If successful, this process, known as impeachment, results in the hearing officer having grounds to give little weight to the testimony given by the witness and, in the worst case, to dismiss it from consideration altogether.

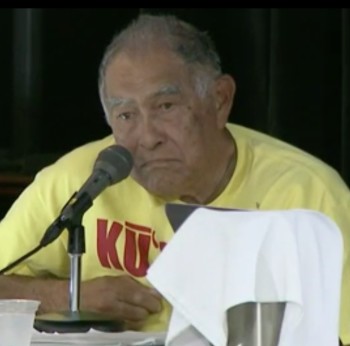

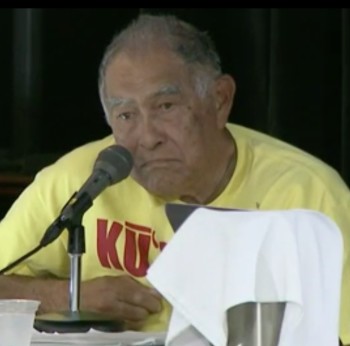

One such case in point: The cross examination of Clarence Fook Tam “Kukauakahi” or “Ku” Ching, a party to the contested case proceeding, by Ross Shinyama, an attorney representing the TMT International Observatory, LLC, which proposes to build the telescope near the summit of Mauna Kea. Ching took the witness stand on his own behalf on January 26.

Shinyama asked Ching, a former attorney who said he had practiced on O`ahu for “at least 14 years,” whether the Hawai`i Supreme Court had ever disciplined him during that time.

Ching: “What do you mean by disciplined?”

Shinyama clarified: “Were you ever suspended for any reason?”

“I was suspended for two years from the practice of law,” Ching replied. When asked the reason for the suspension, Ching said, “I believe the principal reason for that was someone had obtained a judgment against me for not doing what they thought I should do.”

The Supreme Court order required that, should Ching desire to practice law again in Hawai`i, he would need to take the bar exam again following the two-year suspension. He never did.

“[T]he reason is that from that time – actually, from before that time — I had decided to not practice law in the courts, in the state courts, in the fed courts, because I have problems with jurisdiction,” Ching told Shinyama.

During redirect questioning, Dexter Kaiama, attorney for KaHEA, asked Ching for a further explanation of his suspension and his decision to stop practicing law. “Specifically, what happened was, some people approached me about possibly representing them in an auto accident,” Ching said. “I told them I would think about it. I thought about it. And I did not give them a definitive answer that I would represent them. There was no client-attorney agreement made, no down payment made, and all of that, and I didn’t think that I had actually assumed being their attorney on this case. Yet they took me to court. I refused to show up, so I defaulted, and that was used to suspend my license.”

Ching continued that the suspension was something he had actively sought: “What is interesting is that I tried to get them to disbar me because I didn’t want to practice law in the state of Hawai`i or the feds from then on. And it all ended with the suspension from which I have never tried to retake the bar.”

“I believe that Hawai`i is not part of the United States as there has been no treaty of annexation and that presently the situation is that Hawai`i is an occupied country by the United States,” Ching added.

The Order of Suspension

That was the end of Ching’s testimony for the day – but not the end of the matter.

Among the exhibits proffered by the TMT in support of its case were two documents that related to Ching’s suspension: the report, findings and recommendations of the Office of Disciplinary Counsel regarding Ching; and the Hawai`i Supreme Court’s order of suspension. (To read the exhibits, see: Ching Suspension.)

The ODC’s report runs to 17 pages and discusses not one but three cases in which Ching’s actions as an attorney merited disciplinary action. The first one, which dated back to 1982, involved Ching’s representation of Janie and Mung Hong Yee. The Yees had been injured in an accident and had sought Ching’s help in recovering damages from the responsible party. “From March 1982 to approximately September 1989, [Ching] failed and neglected to file a civil complaint on behalf of Janie Yee and failed and neglected to file a claim for excess wage loss on behalf of Mung Hong Yee prior to the expiration of the statute of limitations in each case,” the ODC found. The Yees sued Ching for malpractice and were awarded damages of more than $42,000.

In the second case, Ching represented a mother whose son was killed in an automobile accident. The sole assets of the estate were proceeds from a personal injury lawsuit against the driver at fault. Another attorney involved in the probate proceedings worked out an arrangement for shared responsibilities with Ching. When Ching failed to live up to his duties under the agreement, including the filing of the final accounting of the estate, and the other attorney was unable to get him to respond to repeated demands, she notified the ODC. “[Ching’s] neglect of the foregoing estate matter, including his failure to complete the documentation to close the estate matter over a substantial period of time, and his failure to timely cooperate with [the ODC’s] investigation of the underlying complaint, constitute violations of … the Hawai`i Code of Professional Responsibility,” the ODC determined.

The third case considered by the ODC concerned Ching’s failure to represent a woman accused of child abuse and neglect who was facing the loss of custody of her children. Ching did not appear at the first scheduled court date of May 13, 1992, then also failed to show on three other rescheduled court dates in May and June of that year. According to the ODC, on June 17, the judge’s clerk attempted to reach Ching at the office phone number he had provided to the Hawai`i State Bar Association Directory and also in the telephone directory. “The clerk ascertained that the number had been disconnected,” with no new phone number provided.

On June 30, the ODC report states, the clerk phoned Ching at his residence. Ching “advised her that he was not actively engaged in the practice of law and acknowledged that he had not formally withdrawn from his cases.” That same day, the judge filed a complaint against Ching with the ODC.

In its report, the ODC found that there were aggravating circumstances: “(a) the existence of multiple offenses; (b) a pattern of misconduct; (c) the existence of a prior offense involving similar misconduct (for which [Ching] received an informal admonition in 1987); (d) [Ching’s] failure to cooperate with [the ODC] investigation and/or to appear in these disciplinary proceedings; and (e) his apparent indifference toward making restitution to the Yees under the judgment obtained against him in the malpractice action.”

On April 14, 1993, the Supreme Court ordered Ching to be suspended from the practice of law for two years, as recommended by the ODC. At the end of that time, if he wanted to practice law again, he would have to retake the bar exam, satisfy the judgment against him, and reimburse the ODC for the cost of the proceedings against him.

Ching’s Response

On March 16, Ching filed a motion in opposition to the TIO’s introduction of the order of suspension and the ODC report.

In an effort to amend the statements he made on January 26, Ching said he had “told the ‘full truth to the best of my knowledge’ in response to questions” posed by Shinyama about the “so-called Yees’ cases.” He acknowledged, though, that there could be “a possible conflict,” saying that he did agree to represent Mung Hong Yee in his case but not Jamie [sic] Yee. “I reject the suggestion and the subsequent legal finding that I committed legal malpractice on Mrs. Yee’s case by NOT filing the alleged complaint,” Ching wrote. He did not address the two other cases considered by the ODC.

“I believe that [the TIO exhibits] – as far as my credibility is concerned, and relative to the substantive evidence of the contested case hearing, is not material and not relevant, and should NOT be admitted into evidence,” Ching concluded.

Patricia Tummons

Leave a Reply