The Western Pacific Fishery Management Council is wasting no time seeking financial compensation for those in the fishing industry who may claim they have been harmed by President Barack Obama’s expansion of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument in late August.

The Western Pacific Fishery Management Council is wasting no time seeking financial compensation for those in the fishing industry who may claim they have been harmed by President Barack Obama’s expansion of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument in late August.

At its meeting last month — shortly after being advised by counsel of restrictions on lobbying legislatures or the president for funds — the council decided to send a letter to Obama highlighting the expansion’s impacts on Hawai`i fishing and seafood industries and indigenous communities and requesting that the Department of Commerce mitigate those impacts through “direct compensation to fishing sectors.”

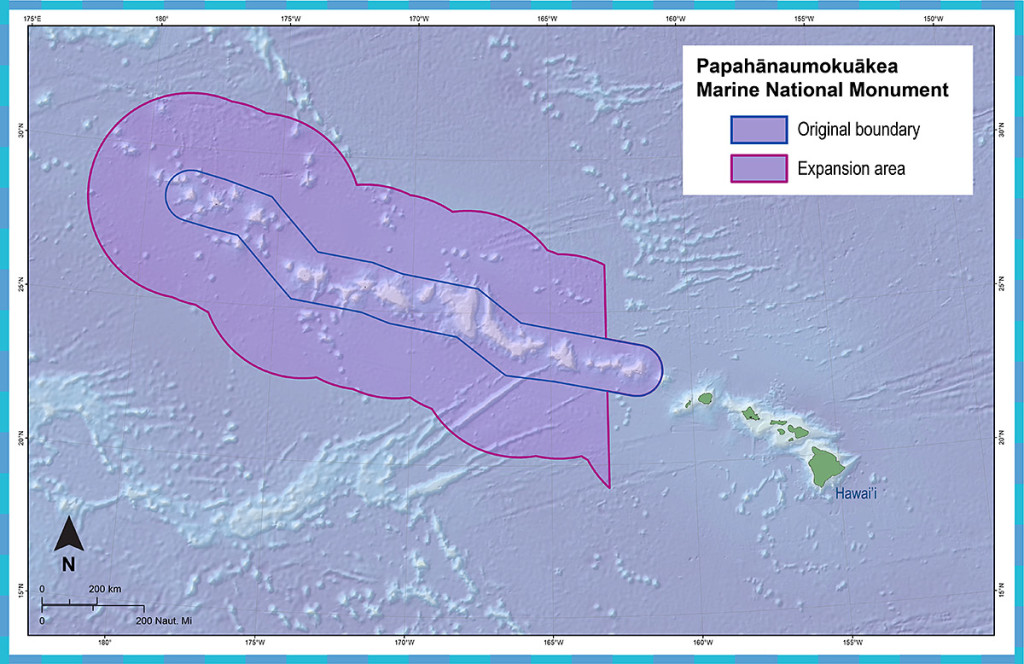

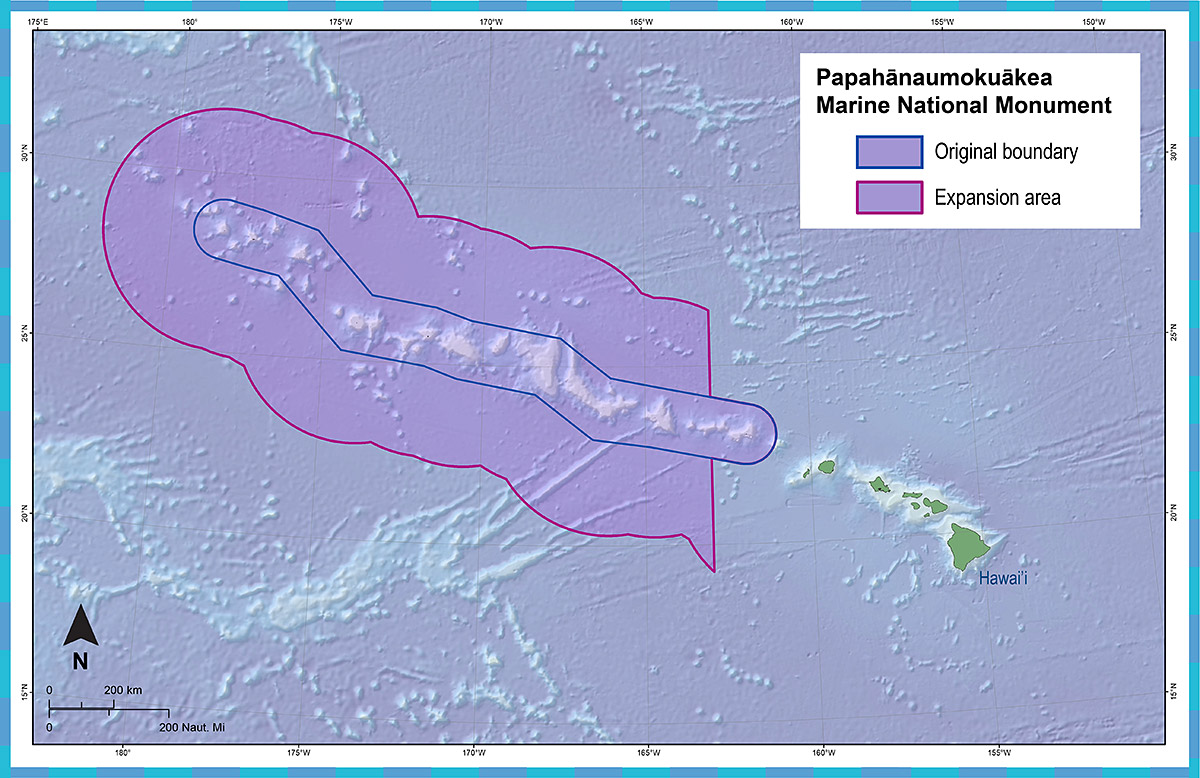

The council’s letter will also include a request that the ban on commercial fishing in the expansion area — which includes the waters between 50 and 200 nautical miles off the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — be phased in. The letter will also ask for “other programs that would directly benefit those impacted from the monument expansion.”

Compensation for fisheries closures in federal waters is not unprecedented. In 2005, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) reimbursed the Hawai`i Longline Association $2.2 million for legal expenses tied to the group’s lawsuit opposing a temporary closure of the swordfish fishery. Also, as part of the same $5 million federal grant that funded the reimbursement, lobster and bottomfish fishers displaced by the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve established by president Bill Clinton also received hundreds of thousands of dollars in direct compensation and funds for fisheries research.

With regard to the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, after it was first established by President George W. Bush in 2006, then-Sen. Daniel Inouye inserted an earmark in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2007 that provided more than $6 million to NMFS for a “capacity reduction program.” That program allowed vessel owners with permits to fish for lobster or bottomfish in the NWHI to be paid the economic value of their permits if they chose to stop fishing well ahead of the date all commercial fishing was to end in the monument, June 15, 2011.

Unlike the bottomfish and lobster fisheries, however, the Hawai`i longline fishery catches the vast majority of its haul in waters outside the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) around the NWHI. And while the reserve and original monument designations permanently closed the door on the former two fisheries, this year’s monument expansion merely forces the longline fleet to shift its effort eastward at a time when it’s already doing that on its own.

Even so, Wespac is pushing for a compensation package for fishers inconvenienced by the monument expansion. Whether or not it’s the council’s place to ask for it is questionable. In his ethics presentation to the council given shortly before it voted to ask Obama for money for the “fishing sector,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) general counsel Fred Tucher advised the council that it cannot use its federal grant to lobby any legislature or the executive branch for more money. The council could be in the clear since it’s asking for money not for itself, but for others. In any case, co-counsel Elena Onaga told the council to run the letter by NOAA’s financial assistance attorneys before sending it out.

Economic Losses

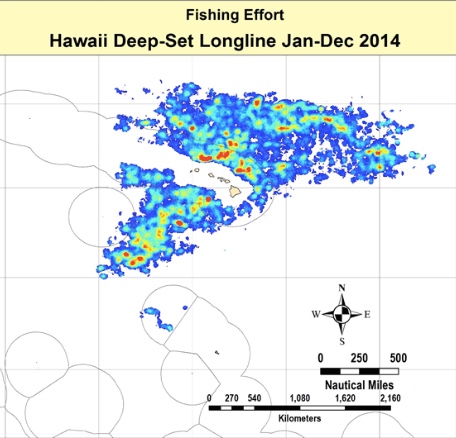

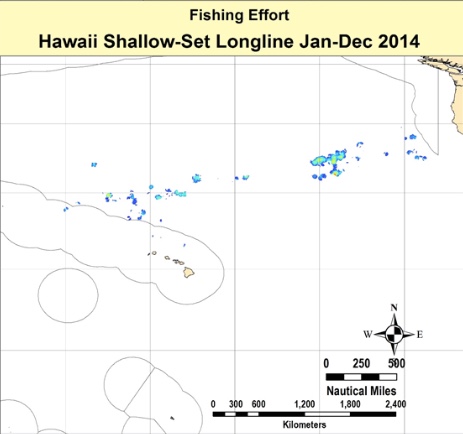

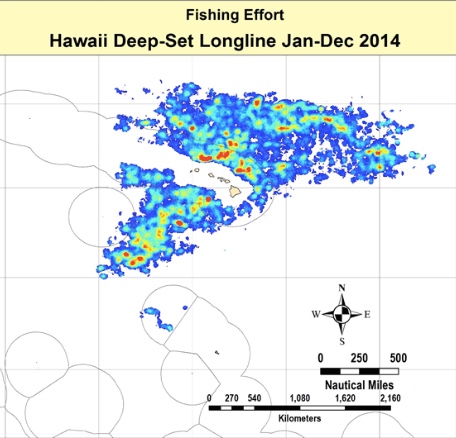

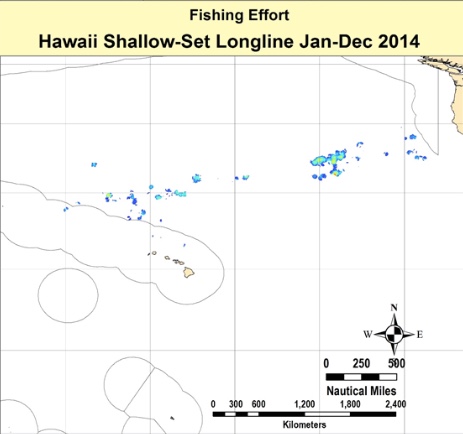

Just how much, if anything, should the federal government shell out to compensate these “fishing sectors”? Justin Hospital, head of the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center’s (PIFSC) socioeconomics program, has done a preliminary analysis of what the economic impacts of the monument expansion might be. In a presentation to the council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee (SSC) last month, he described the maximum direct economic losses likely to be suffered by the Hawai`i deep-set and shallow-set longline fleets.

Between 2010 and 2015, the fleets caught 9.2 percent of their total pounds in the EEZ surrounding the NWHI, he said. In the monument expansion area, the fleets caught less than seven percent of their total pounds.

Hospital’s data suggest that the expansion will affect the shallow-set fleet, which targets swordfish, more than it will the deep-set fleet, which targets bigeye tuna. The swordfish fleet got about 10 percent of its revenue from the expansion area, while the bigeye tuna fleet got about 6.2 percent of its revenue there, he said. In total, the two fleets would lose about $7.8 million in revenue if their effort in the expansion area ended altogether, he said.

With regard to indirect economic losses, he suggested that related industries stood to lose $9 million, household income losses could reach $4.25 million, 75 jobs could be lost, as well as about half a million in tax revenue.

Hospital emphasized that all of his projections should be considered the “upper bounds” of potential economic impacts of the expansion. “To achieve these, we’re to assume this fish is not replaced anywhere else. This is not the case. Fishermen can fish elsewhere, but to move elsewhere, there are costs,” he said.

According to PIFSC, the average cost of a deep-set trip between 2004 and 2014 was $27,842 and an average shallow-set trip cost $53,494. Net revenues per trip were $34,093 and $34,055, respectively.

For the past few years, the Hawai`i longline fleet has had to move its effort outside the U.S. EEZ for nearly half the year because it has hit its international quota for bigeye in the Western and Central Pacific. How much more the monument expansion will increase costs associated with shifting effort remains to be seen.

“These trip costs can be monitored over time to track any added costs [but] could be confounded by quota issues as well,” said Dr. Minling Pan, an SSC member and a colleague of Hospital’s at PIFSC.

Hospital told the SSC that his program will monitor trip costs, revenues, and other economic performance indicators to help discern continuing impacts of the expansion. The full council, however, wanted immediate answers. At its meeting held a week after the SSC met, Wespac asked PIFSC’s socioeconomic program to submit by the end of last month its analysis of the monument expansion’s impact on Hawai`i’s longline fleet and broader fishing and seafood industries.

Concerned that the monument expansion will perhaps increase fishing pressure on yellowfin tuna, the council also asked PIFSC to analyze the change in longline effort around the Main Hawaiian Islands due to the monument expansion in relation to troll-caught yellowfin.

Seth Hostmeyer, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Global Ocean Legacy, told Environment Hawai`i that he’d like to see proof of any economic losses in the fishing sector first. He pointed out that in 2014, Wespac representatives argued that the establishment of the Pacific Remote Island Area Marine National Monument would be devastating to the Hawai`i longline fleet, yet after the monument was created, the fleet had a record catch.

“Their messages aren’t adding up,” he said, adding that he doubted there will be any evidence of economic harm as a result of the Papahanaumokuakea expansion. That the Hawai`i fleet recently hit its bigeye tuna quota in record time and is seeking to increase quota transfers from Pacific island territories proves that it is confident it’s going to continue to catch a lot of fish, he said.

Horstmeyer speculated that even if there were proof of some economic loss, it’s “highly unlikely” the federal government will provide financial compensation. In the past, such funds reached Hawai`i via earmarks, which have since been banned. He said in today’s Congress, getting new money into the budget is challenging. What’s more, arguing for compensation would be “hard to get when you’re paying your crew 70 cents an hour or wages certainly below minimum wage,” he said, citing a recent Associated Press report on poor working conditions suffered by some of the Hawai`i longline fleet’s foreign crew. Paying crews the federal minimum wage might cost more than whatever additional fuel might be required as a result of the monument expansion, Horstmeyer said.

***

Council to Draft

Monument Fishing Rules

About a week before President Obama signed the proclamation establishing the monument expansion area, Wespac had proposed alternative schemes that would fully protect the sea floor and the historic World War II relics, as well as the northern half of the waters surrounding the NWHI. But they would have allowed longlining to continue around Necker, French Frigate Shoals, and Gardner pretty much as it has been. The president ultimately chose to stick with the configuration proposed by Sen. Brian Schatz, making more than 60 percent of the waters around the Hawaiian archipelago off limits to commercial fishing.

“‘This is the darkness and blackness’ was certainly my feeling after the expansion,” Wespac National Environmental Policy Act coordinator Eric Kingma told the council’s SSC last month. Still, he continued, “It’s a new day. The monument happened, the expansion happened, and now we’re moving on.”

As hard as Wespac fought against the expansion, the agency is now responsible for recommending to NOAA fishing regulations for the area. The August 26 proclamation establishing the expansion area gives the secretaries of Commerce and Interior three years to develop regulations implementing its directives. In addition to banning commercial fishing, those directives allow for non-commercial fishing, so long as the fish caught aren’t sold, bartered, or traded. Native Hawaiian traditional, customary, cultural, subsistence, spiritual, and religious practices — which may include some fishing — are also allowed.

At the council’s SSC meeting, member Craig Severance suggested that customary exchange be allowed as it is in other monuments.

“Customary exchange means the non-market exchange of marine resources between fishermen and community residents, including family and friends of community residents, for goods, and/or services for cultural, social, or religious reasons. Customary exchange may include cost recovery through monetary reimbursements and other means for actual trip expenses, including but not limited to ice, bait, fuel, or food, that may be necessary to participate in fisheries in the western Pacific,” according to a NOAA fisheries compliance guide.

In the Marianas Trench, Pacific Remote Islands, and Rose Atoll marine national monuments, customary exchange is allowed under a non-commercial fishing permit. Customary exchange “helps to preserve traditional, indigenous, and cultural fishing practices, on a sustainable basis,” the guide states. Customary exchange by fishermen fishing under a recreational charter permit is prohibited. With regard to the Papahanaumokuakea monument expansion, Severance said the council may need supporting data if the consensus is to employ that concept.

Bartering — which is prohibited — seems similar to customary exchange, which has been criticized by some in the past as a means to subvert commercial fishing bans. Severance, however, argued, “barter implies a negotiated cost. Customary exchange is exchanging with family, friends … It’s not barter, it’s culture.”

Wespac executive director Kitty Simonds, however, seemed more concerned with developing regulations for fishing by native Hawaiians.

“I think where we’ll have a problem is ‘native Hawaiian.’ The Hawaiians won’t like it. They are looking to a government to government agreement. The complexity is with the Hawaiian community,” she said.

At the full council meeting, members voted to direct staff to begin drafting options to amend the Hawai`i and pelagics Fishery Ecosystem Plans that include draft regulations that would:

- prohibit commercial fishing;

- allow non-commercial fishing;

- allow native Hawaiian traditional fishing practices, including subsistence fishing; and

- regulate other activities as appropriate.

Only one member of the public offered testimony on the matter. Hawai`i Fishing News writer Robert Duerr argued in an email that sportfishing is “a priority of the U.S. Congress” and should be allowed in the NWHI.

“Make it a priority to have private contractors provide air transport into Midway. The government should have designated accommodations for fishermen. If government planes are flying, seats should be available to fishermen. At the very least, catch and release should be allowed throughout the NWHI on all species. Depending on stock assessment, catch-to-eat should also be allowed with an allotment for take-away home consumption. If there are government culling programs, sport fishermen should be the first to have access,” Duerr wrote.

Although he didn’t necessarily oppose the idea of recreational fishing in the expansion area, Pew’s Horstmeyer doubted it would ever happen. “Nobody goes up there to recreationally fish,” he said.

With regard to Wespac’s request that the commercial fishing ban be phased in, Horstmeyer said he believed that the ban was supposed to become effective immediately. “When the ink was dry [on the presidential proclamation], the commercial fishing should have ceased,” he said. (The monument expansion proclamation does not specifically include a grace period for commercial fishing, as the original monument proclamation did for commercial bottomfish and pelagic fishing.)

Funding for Co-Managers

In addition to the letter to Obama on the Papahanumokuakea monument expansion, the council voted to send letters to the Secretary of Commerce asking for more funding to help the state of Hawai`i, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa co-manage the Papahanaumokuakea (and expansion area), Marianas Trench, and Rose Atoll monuments, respectively. (Given the lecture from counsel it received earlier about lobbying restrictions, the council chose to address the letter to the Secretary of Commerce rather than President Obama.)

Although the state of Hawai`i does receive some federal funding for the management of the Papahanumokuakea monument, the territories don’t receive any funding for theirs, according to Mike Tosatto, head of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Pacific Islands Regional Office.

— Teresa Dawson

For Further Reading

- “Debate Heats Up Over Potential Impacts of Expanded Monument on Longliners,” “Wespac, Staff Members Fulminate Against Expanded Marine Monument,” “Proponents Argue NWHI Monument Expansion Would Protect Sea Bed, Cultural Resources,” and “NWHI Advisory Council Supports Plan to Keep Middle Bank Open to Fishing,” July 2016.

- “Advisory Council Debates Details of Proposed Monument Expansion,” June 2016.

Leave a Reply