Last month, Environmental Court Judge Jeffrey Crabtree denied a motion by Alexander & Baldwin, Inc., and East Maui Irrigation Company to revert the 31.5 million gallons of water a day cap he set in June on East Maui stream diversions back to 40.49 mgd. That higher number was the limit set by the Board of Land and Natural Resources when it voted last November to continue their water permits for another year.

Judge Crabtree’s cap was part of his decision ordering the Land Board to grant the Sierra Club of Hawaiʻi’s request for a contested case hearing on the permits. The non-profit organization had argued that the Land Board’s limit was too high and that much of that water should be left in the streams. Crabtree agreed, noting in his decision that in addition to the water diverted under the permits, the companies can and do pump millions of gallons of groundwater a day to help meet their needs in Central Maui.

He reduced the board’s limit to reflect the facts that A&B/EMI could pump 4 mgd of groundwater, that a 2.79 mgd ‘cushion’ the board had allotted was not a reasonable or beneficial use, and that the 2.2 mgd the board set aside for reservoir, dust control, fire, etc., could be taken from the unused portion of the 7.5 mgd allocation to Maui County. (Since January 2020, the county has used at most 4.83 mgd and typically uses much less.)

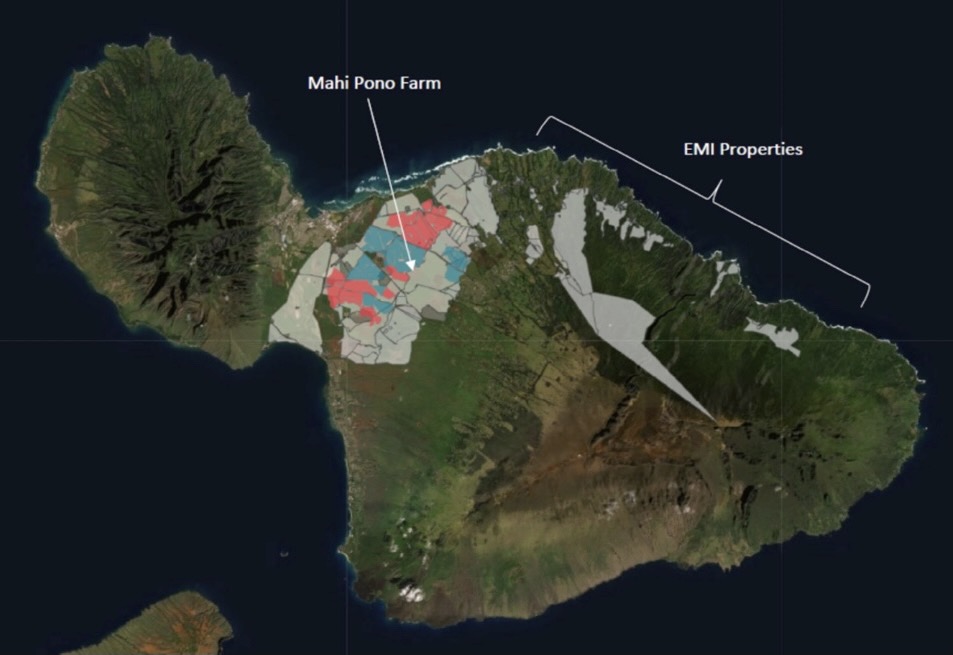

Two weeks after Crabtree’s decision, A&B and EMI sought a revision. Their attorneys — Trisha Akagi, David Schulmeister, and Mallory Martin — argued in a motion to modify the permits that his cap was too low to meet Maui County’s needs and those of Mahi Pono, which co-owns EMI and has been working for years to fill A&B’s former sugarcane fields in Central Maui with diversified agriculture.

They noted that Mahi Pono has 62 more planted acres now than it had when the Land Board voted to continue the permits. What’s more, they stated that Mahi Pono intends to plant an additional 1,568 acres of orchard trees in its East Maui fields this year.

They included a chart prepared by Mahi Pono VP Grant Nakama of anticipated water needs of Mahi Pono’s various crops for 2023, some of which would reportedly require as much as 5,089 gallons per acre per day. In total, he determined that the crops would require 31.53 mgd this year.

With an additional 6 mgd going to the Maui Department of Water Supply, 1.5 mgd going to the county’s Kula Agricultural Park, .07 mgd going to historic/industrial uses, and 2.22 mgd going into reservoirs, or used for fire protection, dust control and/or electricity generation, the attorneys argued that A&B/EMI would need to divert 41.32 mgd from the watersheds in East Maui covered by the permits.

Even though they asked to divert 40.49 mgd, they recognized that that lower amount may still exceed actual need at times. “EMI will only divert what is needed on any given day to deliver sufficient water to meet the needs of the County, historic/industrial uses, and Mahi Pono’s diversified food crops,” they promised.

“Because the cap imposed on the [revocable permits] is defined and calculated on a monthly average, the cap must be able to accommodate the month with the highest anticipated need, even though that amount of water may not, and likely will not, be diverted every month,” their attorneys wrote.

Maintaining a cap that exceeds actual need would give Mahi Pono some flexibility. “EMI must be able to divert up to the amount of the monthly cap to make up for days where there was insufficient surface water. Because EMI has little to no notice when drier weather conditions will abate and more surface water will become available, reducing the cap during drier seasons would eliminate much needed flexibility in EMI/Mahi Pono’s water planning,” they wrote.

They argued that Crabtree had improperly deducted from the Land Board’s cap the amount of groundwater available to Mahi Pono. Although the company has pumped about 4 mgd at times, they pointed out that because the well water is brackish, it has to be mixed with surface water, so it’s not a 1:1 replacement. They added that on average, Mahi Pono pumps only 2.16 mgd of groundwater.

They also argued that “the numbers just do not add up” when system losses are considered. Based on a Commission on Water Resource Management determination that 22.7 percent of water diverted from East Maui is lost to leaks, seepage, evaporation, etc., the attorneys pointed out that system losses alone from a diversion of about 40 mgd would exceed the county’s 7.5 mgd allocation.

Rebuttal

In its response, the Sierra Club began by disputing Nakama’s claimed water requirements for Mahi Pono’s various crops.

“This court should not find Mr. Nakama’s opinion to be reliable given (a) the self-interest involved, (b) his past inaccurate predictions, and (c) the inflated estimate of water demands per crop. In August 2020, Grant Nakama claimed that a cap of 25 mgd ‘would have a high detrimental impact on the expansion of our farming operations.’ Yet, Mahi Pono suffered no hardship from the cap imposed by the court on July 31, 2021,” the Sierra Club’s attorney, David Kimo Frankel, wrote. He added that Nakama had also presented an inaccurate estimate of how much water was needed for historic/industrial uses that year. He estimated that 1.1 mgd was required.

“Yet, when Mahi Pono finally installed meters, the data revealed that Nakama had wildly exaggerated how much water was needed for so-called ‘historic/industrial’ uses. These uses did not require 1.1 mgd. They did not even require 100,000 gallons. They needed less than 50,000 gallons,” Frankel wrote.

The chart Nakama provided to the court estimated that at full maturity, some crops would require 3,392 gallons per acre per day. Most would require 5,089 gpd at first planting AND at full maturity, according to Nakama.

In the second quarter of this year, Mahi Pono’s orchard crops used 1,930 gallons per acre per day and its row crops used only 1,287 crops per acre per day, Frankel noted.

“It is generally understood that in Hawai‘i diversified agriculture requires no more than 2,500 gallons per acre per day,” he stated, noting that A&B’s own executive VP Meredith Ching had basically testified to that in court.

“If Mahi Pono has 10,430 acres in cultivation by the end of 2023 (and those crops required 2,500 gallons per acre per day, which is more than they have ever needed), Mahi Pono would need 26.07 mgd – which is still less than A&B requested for irrigation just a few months ago, and less than what this court allocated,” he continued.

To determine their daily crop water requirements, the companies considered reports prepared by the University of Hawaiʻi, one on growing alfalfa and another that applied the Irrigation Water Requirement Estimation Decision Support System (IWREDSS) to various crops.

The IWREDSS is a GIS-based simulation model that can estimate irrigation requirements for crops grown in different areas throughout the state, using different irrigation methods and practices.

A&B/EMI’s attorneys explained that “the crop coefficients taken from the Producing Alfalfa in Hawaiʻi report were the reference point and then adjusted based on the crop coefficients in the IWREDSS report.” Alfalfa was chosen as the reference crop because its root system is similar to citrus trees and other “permanent-type crops,” according to Mahi Pono’s Ceil Howe III.

Frankel pointed out that the company had stopped short of actually using the model, and chose to just rely on the UH report. “It cherrypicked one set of data,” he argued.

“But,” he continued, “CWRM’s Ayron Strauch actually used the IWREDDS software. CWRM calculated Mahi Pono’s surface water irrigation needs at full build-out. It estimated that citrus would require 2,541 gallons per acre per day, half of what A&B and Mahi Pono claim.”

The crop water requirement numbers Nakama presented, as well as his declaration, contained speculative opinions that were inadmissible under Hawaiʻ Rules of Evidence, he added.

Whatever the requirements are, the Sierra Club argued that Mahi Pono can pump as much as 14.5 million gallons of groundwater a day to help meet its needs: It has a 10 mgd capacity well above the Haʻikū aquifer, and the Water Commission has determined that Mahi Pono could feasibly pump about 4.5 mgd from its wells in the Paia aquifer.

As recently as June, Mahi Pono pumped 7.45 mgd of groundwater, according to A&B’s quarterly reports.

Frankel noted that A&B’s own exhibit on the salinity of the well water showed that it’s relatively fresh. Between the third quarter of last year and the second quarter of this year, the three wells used had chloride levels ranging from 151 mg/L to 300 mg/L. His brief observes in a footnote that water with less than 250 mg/L of chloride is not considered brackish.

“A&B’s [final environmental impact statement for a long-term lease for the water] calls for mixing 1 mgd of groundwater with 2.33 mgd of surface water (essentially a 30:70 mix) based on an assumption that groundwater is composed of 703 mg/L of chlorides. The groundwater is nowhere near that salty. … If Mahi Pono were to use 21 mgd of surface water, it could easily mix in an additional 9 mgd of groundwater for 30 mgd of irrigation water,” Frankel argued.

A&B and EMI also have access to streams that are outside the permit areas but feed into EMI’s diversion system, he wrote, adding that in October 2022, the companies took 4.79 mgd from these streams.

“A&B’s quarterly reports reveal how much water A&B has taken from these streams; they say nothing about how much more water A&B could have taken from them. A&B cannot beg this court for more water while failing to disclose that it has additional surface water available as well,” he argued.

And then there’s the unused water the companies divert to unlined reservoirs.

“In 2022, A&B estimated that 2.22 mgd would remain in the ‘catch-all’ category for ‘reservoir, fire protection, evaporation, dust control and/or hydroelectric uses.’ Far more than that, however, winds up in the reservoirs. … April 2023: 6.36 mgd. May 2023: 5.25 mgd. June 2023: 4.99 mgd. … If there is any shortage of water, A&B can use more than 4 mgd that routinely go unused,” Frankel stated.

The Ruling

After two hearings on the motion, Judge Crabtree issued an informal ruling on September 8. (He had not signed a final order by press time. As of late September, attorneys for A&B/EMI, the Land Board, and the Sierra Club were still in disagreement over the order’s proposed language.)

Crabtree found that A&B and EMI had failed to meet their evidentiary burden to demonstrate their actual stream water needs.

He wrote that the most recent nine months of water use data confirm that Mahi Pono has been using substantially less water than the 27.91 mgd he allocated for diversified agriculture under his cap. Just in the second quarter of this year, the cap allowed for the diversion of 30 mgd more than what Mahi Pono used, he noted.

With regard to the argument by A&B and EMI that the cap needs to be increased to account for water wasted via leaks in the diversion system, Crabtree stated that he would not agree to do so easily.

The well-known need to reduce waste in the irrigation system “must be addressed at some point rather than continuing to kick the can down the road,” he wrote. However, he continued, “increases in water diversion will not automatically be granted for millions of gallons per day of system waste absent evidence that X amount of system waste cannot reasonably be avoided, and absent evidence that the court’s current cap is not working — as opposed to claims that the cap will not work for unscheduled future planting that may not occur for months. The current information provided to the court on system waste does not explain the large gap between the current cap and actual use. In the Second Quarter of 2023 example used above, and even applying CWRM’s estimate of 28 percent in system losses (which does not completely and always apply), the court’s cap is still significantly higher than the combined amount of the water actually used for crops and the estimated water lost to system waste,” he wrote.

Crabtree also found that Mahi Pono’s plans to plant 230,000 trees on 1,568 acres in the third and fourth quarters of this year are not firm enough to warrant the cap increase that A&B and EMI had requested.

“The court is not willing to increase the cap for September, October, and November if the new trees will not be planted until December. That would be an enormous waste of water unless an explanation is given why (and how much) the empty acres need to be watered before the trees are actually planted. Are the new trees ‘in a nursery’ in upcountry Maui being watered from a source the court has already allocated water for? Did the devastating fires on Maui in August push back Mahi Pono’s timetable? The court does not know one way or the other; however, when a party has the burden of proof to justify using a limited public trust resource, this lack of information means the court cannot justify increasing the cap at this time,” he wrote.

He added, “Even if seepage or system loss is as much as A&B argues, there is still no evidence the cap is not high enough now. There are no pictures of wilted trees, there is no filed Declaration that Mahi Pono decided not to plant more crops because of an actual water shortage. There is no evidence that the reservoirs are dry and the ground water is insufficient to sustain the crops until rainfall comes. Bottom line, the evidence in the record supports the court’s conclusion that the court’s cap is sufficient to support Mahi Pono’s diversified agriculture venture to date.”

Nakama’s estimates of daily water requirements for the trees to be planted also confounded Crabtree. Nakama had asserted that the trees would need 5,089 gallons per acre per day (GPAD) in the first six months of planting, then a reduced amount after 18 months, then back up to 5,089 some four and a half years after planting, when the trees should be fully mature.

“Whether or not this information is accurate is material to establishing a reasonable stream diversion cap. No industry standard or other established authoritative source was given for this data. Since the GPAD/[stage of maturity] data would be applicable to hundreds of thousands of new trees and at least 1,630 newly planted acres, it is a significant number.

“As near as the court can tell, Mr. Nakama’s Exhibit A makes no allowance for time of year. It concludes that 5,089 GPAD is necessary per acre for newly planted acres (but varying based on tree maturity), and that amount of water should be allocated every month of the year. …

“The court is no agricultural expert, so if in fact there is a recognized industry standard applicable to Maui showing these newly planted trees need as much water when first planted as when they are 5+ years old, certainly the court will consider such evidence. But it is definitely not proven by Mr. Nakama’s chart or Declaration,” Crabtree wrote.

Despite A&B’s and EMI’s promise that they would only divert the amount of water that will actually be used, even if the cap is set at the maximum amount needed in a given month, Crabtree was not convinced. Setting a static cap that would allow the companies to divert the “high need” amount every month for the entire year “virtually guarantees that millions of gallons per day will be wasted during the wetter months. … Wanting a ‘cushion,’ though understandable, cannot be justified if it means a foreseeable, preventable, and substantial waste of a public trust resource,” he wrote.

He argued that the cap should reflect the reality that water needs vary during the course of a year.

“Allowing the same maximum amount every month ignores this reality. If adjustments cannot be made every month, why not each quarter? Every six months? … A monthly cap may be justified historically, but better strategies are needed to both conserve resources and cover additional beneficial uses. … A sliding cap could be proposed, such as X (a higher) amount can be diverted when the stream is running between stream volumes of A and B (higher stream volume in wetter months), and only Z (a lower amount) can be diverted between specific lower stream volumes in drier months,” he wrote.

Crabtree also agreed with the Sierra Club that alternative sources of water (groundwater, other steams, reservoirs) are available to A&B and EMI (and Mahi Pono).

Despite his denial of A&B’s and EMI’s motion, he invited them to return to court with better data on Mahi Pono’s needs, as well as a proposal for a more adaptive diversion schedule. He also ordered the parties to try to mediate these matters with help from retired Environmental Court Judge Joseph Cardoza, if he was willing.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply