Board Denies Petition for Contested Case On Mosquito Control Suppression Project

The state Board of Land and Natural Resources’ May 12 meeting began at 9:15 a.m. and stretched well past dinnertime. As the board heard public testimony on one of its last agenda items, board member Aimee Barnes could not let the insulting innuendo from one testifier go without a response.

The Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife had requested that the Land Board deny a petition for a contested case hearing filed in April by the nonprofit Hawaiʻi Unites and its president and founder, Tina Lia of Maui.

Lia is a vocal opponent of plans by state, federal, and private entities to release into the forests of East Maui house mosquitoes carrying a different strain of the Wolbachia bacteria than what’s carried by mosquitoes in the wild. The incompatible bacteria strains will render any offspring inviable, and, hopefully, result in a reduction in the mosquito population and transmission of avian malaria, which has devastated native bird populations.

Specifically on Maui, avian malaria has pushed the kiwikiu and ʻākohekohe to the brink of extinction.

Lia submitted her written request after the Land Board denied her oral request at its March 24 meeting and accepted an environmental assessment for the project.

At the May meeting, Lia testified in opposition to DOFAW’s recommendation. She argued, as she has in the past, that the project was experimental and could cause the extinction of the forest birds and have other devastating consequences. She argued that the Land Board needed to honor constitutional due process and grant a contested case hearing.

In recommending denial of her request, DOFAW noted in its report to the board that neither Lia nor Hawaiʻi Unites asserted a property interest that would trigger a due process analysis.

Among the testifiers who supported Lia’s petition was Juhl Rayne. She argued that the mosquito release will do more harm than good, adding, “We definitely have to have this experimental thing looked into. … It’s quite obvious any decision other than that is, I don’t know, being paid for by someone.”

Before the board moved onto the next testifier, Barnes asked to address Juhl’s last point.

“This is an all-volunteer board. I’ve been here since 9 o’clock this morning. I don’t get paid for this. I have two small children at home. I take my time out of my day to contribute to our state and I take accusations that I or anybody else on this board has been paid to make any decision very personally. So please be thoughtful when you make accusations like that. It’s very offensive,” she said.

The board ultimately voted to accept DOFAW’s recommendation for the reasons given, noting that Lia and Hawaiʻi Unites had already filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in Environmental Court.

The Lawsuit

In their complaint, filed May 8, Lia and Hawaiʻi Unites argue that the Land Board and DLNR violated the Hawai‘i Environmental Policy Act by not requiring an environmental impact statement for the mosquito suppression project.

“Hawaiʻi Unites has repeatedly presented documented, compelling evidence of the risks and impacts of the biopesticide mosquito project to the BLNR. Rather than acknowledge and address the organization’s concerns, the BLNR has acted in a consistently dismissive and disruptive manner towards this testimony,” the complaint states.

“Tropical disease and vector expert Dr. Lorrin Pang, speaking as a private citizen, has expressed concerns about horizontal transmission (ʻhorizontal spread’ or ʻhorizontal transfer’) of the introduced Wolbachia bacteria strain to wild mosquitoes and other insects, including other insect vectors of disease. … Peer-reviewed studies have shown Wolbachia bacteria in mosquitoes to cause increased pathogen infection and to cause mosquitoes to become more capable of spreading diseases such as avian malaria and West Nile virus,” they continue.

“Male mosquitoes transmit bacteria and pathogens to females. Infected females can spread disease to birds (including endangered native birds), other animals, and humans,” they stated.

The complaint also raises concerns over the impacts using drones to drop biodegradable packages of mosquitoes into the forest areas. There could be “up to 134 drone flights per week over the project area for the life of the plan – likely at least 20 years as stated in the final EA. … Drone hovering; risks of breeding birds being flushed from active nests; disturbances of day roosting Hawaiian hoary bats; and risks of disturbing bat pup rearing are all noted impacts,” it states.

The state had not yet filed a response to the complaint as of late May. However, at the March 24 Land Board meeting, DOFAW administrator Dave Smith did address some of the concerns Lia and others have raised.

Smith pointed out that the species of mosquito and the strain of Wolbachia are already found in Hawaiʻi. He also noted that if some females are released along with the males, “even if the female bites you, they have Wolbachia already. It’s not like they’re giving you something. … The other thing with mosquitoes is they only live for a very short period of time. People say, ‘What if a female got out that has this different Wolbachia strain?’ We could just pause and they could be bred out of the population in a very short period of time.”

A scheduling conference for the case has been set for August 3.

Board Approves Public Hearings On New Rules for Uhu, Kala, and More

Last December, the DLNR’s Division of Aquatic Resources asked the Land Board to authorize public hearings on a rules package that would set new limits take of manini (convict tang), kole (goldring surgeronfish), kala (bluespine unicornfish), uhu (parrotfish), and papa pualoa (Kona crab).

Several commercial fishers complained that some of the more restrictive limits — the bag limit of two per person per day for kala and uhu, specifically — would put them out of business. Even though those fish are considered by scientists to be overfished, the Land Board deferred making a decision and directed DAR to craft accommodations to allow commercial fishing to continue, but not expand.

On May 12, DAR returned with a new rules package that would require commercial marine dealers of uhu or kala to register as such to purchase, possess, and sell those species.

For commercial fishers of uhu, the following would apply:

Only uhu palukaluka (initial-phase redlip parrotfish) would be allowed for commercial harvest and sale, and there would be a daily bag limit of 30 per commercial marine license (CML) holder;

Only fish between fourteen and twenty inches in length could be caught and sold, and commercial harvest and sale would be prohibited during the peak spawning months of February through May.

Fishers must obtain a valid Commercial Uhu Fishing Permit, which may be issued to anyone who holds a valid CML, pays a $100 permit fee, provides proper identification, and has caught and sold at least 340 pounds of uhu within the past twelve months as verified through commercial catch reports and/or commercial marine dealer reports.

Commercial fishers of kala would have a daily bag limit of 50 per CML holder and would also have to have a Commercial Kala Fishing Permit. The minimum size of kala caught would be the same as the proposed non-commercial size limit: 14 inches. Commercial harvest or sale would be prohibited during peak spawning months of April through July.

To obtain the commercial kala fishing permit, an applicant would have had to have caught and sold at least 100 pounds of kala within the past twelve months.

Those seeking commercial permits for uhu or kala who did not have documented sales would receive a probationary permit. If probationary permittees did not catch their minimum amount, they could not get a permit for the following season. Fishers who did not sell to dealers would need to report their cash sales to DAR.

DAR also proposed setting commercial annual catch limits for uhu and kala that represent approximately 75 percent of the average annual reported commercial catch over the past five years. For kala, that would be 10,000 pounds. For uhu, it would be 34,000 pounds.

If the ACLs are reached, then DAR would close the fisheries. However, dealers with valid receipts for the fish would still be allowed to sell them if the fisheries closed because ACLs were reached.

Despite all of the accommodations DAR proposed for the commercial fishers, several still testified in opposition. Some argued that the state’s assessment of the abundance of the fish species was wrong, and that both uhu and kala were plentiful. Others testified that the bag limits would result in a lot of discarded, dead and, in their eyes, wasted fish.

DAR biologist David Sakoda countered that the discarded fish aren’t wasted, since they will remain in the ecosystem and get eaten by something.

In addition to the uhu and kala commercial catch provisions, DAR also proposed kole regulations that would allow the harvest by aquarium collectors of kole less than five inches in length “pursuant to the terms and conditions of a valid aquarium fish permit and other aquarium fishing regulations.”

Despite the continued opposition from some commercial fishers, board member Kaiwi Yoon made a motion to approve DAR’s request to send its new rules out to public hearings.

With regard to the opposing characterizations of the populations of the fish targeted by commercial fishers, Yoon said there was “a big delta between choke and not choke. I don’t know what data set to internalize.”

He noted that in the Hawaiian language, kala means “to forgive, to let go, to free. Interestingly enough, uhu means to restrain, to hold back, to pull. … Here we have these two fish trying to talk to us and somewhere in the middle is where the sweet spot is.”

After an executive session, Yoon amended his motion to delete DAR’s proposed rules regarding the commercial aquarium collection of kole. He said that the Land Board would deal with aquarium collection matters at another time.

With that, the board unanimously approved Yoon’s motion.

For more background, see, “Efforts to Accommodate Commercial Fishing Delays Hearings on Proposed Catch Limits,” from our January 2023 issue.

Sandalwood Seed Sharing, Conservation Easement in South Kona

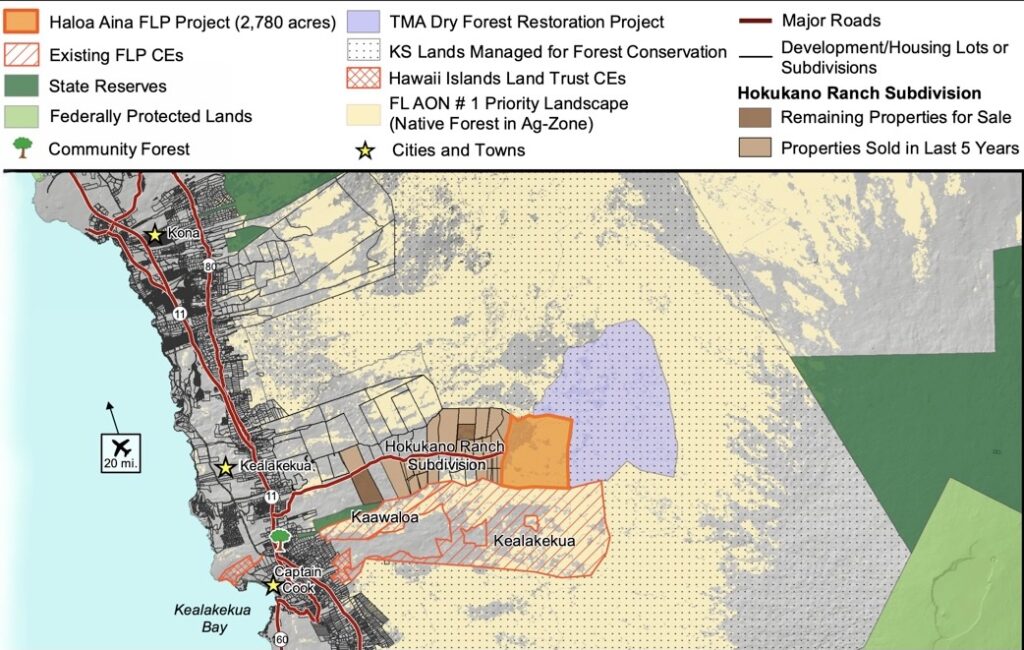

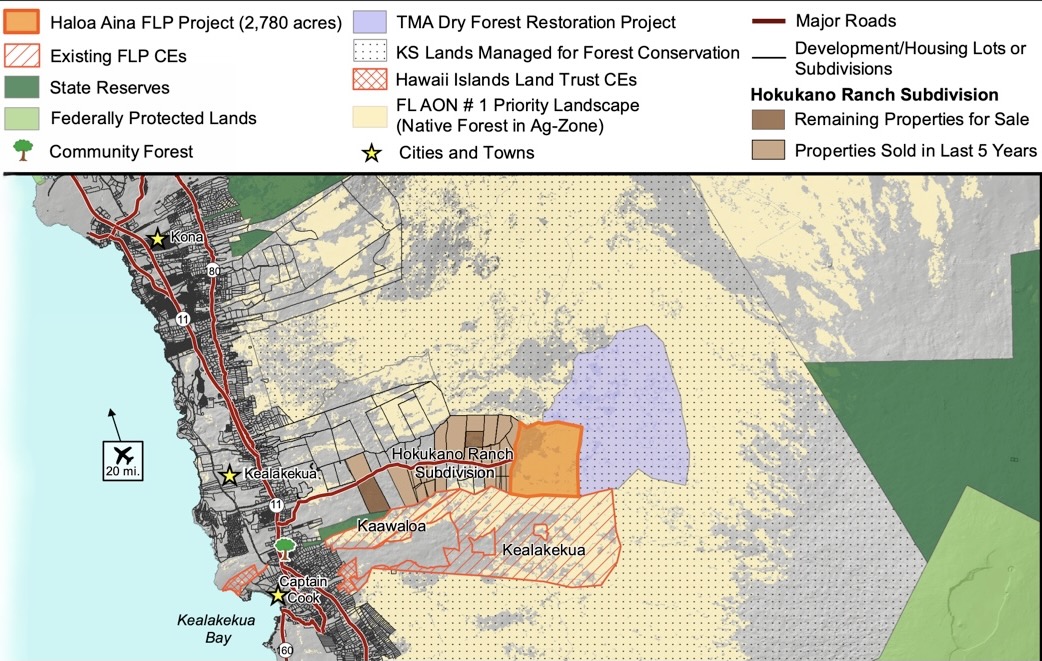

On May 12, the Land Board approved a request by DOFAW to enter into a memorandum of agreement with Haloa Aina LLC regarding the sharing of sandalwood seeds for use in the division’s orchard planting efforts. And on May 26, the board approved the acquisition of a perpetual conservation easement over three parcels owned by the company in Kealakekua, South Kona, totaling 2,733 acres.

DOFAW’s May 12 report to the board noted that Hawaiian sandalwood are “highly valued economically, ecologically, and culturally, and are threatened by habitat loss, predation, fire, and lack of regeneration.”

To protect the trees, the division is establishing a network of sandalwood seed orchards on public and private lands throughout the state under a Landscape Scale Restoration (LSR) Agreement with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USDA-FS).

“The purpose of this project is to produce high quality, eco-region specific seed for native forestry restoration efforts. Haloa Aina LLC, a family-owned company that is dedicated to restoring native dryland forest, has expressed willingness in hosting a seed orchard site on their property,” the report states.

The MOA with Haloa delineates the responsibilities of DLNR and the company with regard to the seed orchard site, Under the agreement, the seeds produced would be split 50-50 between the DLNR and Haloa.

With regard to the purchase of the conservation easement on Haloa’s lands above the Hokukano Ranch subdivision, DOFAW is awaiting the results of an appraisal before it can expend funds received from the federal Forest Legacy program and the County of Hawaiʻi’s Public Access, Open Space, Natural Resources Preservation Fund. Haloa, previously known as Jawmin, LLC, purchased the three properties in 2009 for $9 million.

The easement is needed to “permanently protect 2,733.106 acres, more or less, of dry montane forest (4,500- to 5,500-foot elevation) located in the South Kona region. … The project area’s forest provides essential Hawaiian sandalwood,” a DOFAW report states.

“In addition to historic declines, populations of ʻiliahi in the region continue to decline due to ongoing threats such as unsustainable logging, housing development, cattle grazing, invasive species, and low natural recruitment. With high land value in the region, active subdivision and land sales are happening immediately adjacent to Haloa Aina. The CE will forfeit the right of the landowner to subdivide, protecting the property from development in perpetuity and ensuring this property stays a working and recovering native forest. This forest will increase economic opportunities to rural valuable woods in the world.

“This project will connect over 400,000 contiguous acres of adjacent managed forests including two Forest Legacy project conservation easements also held by the state (Kealakekua Mountain Reserve and Kaʻawaloa), forested lands managed by Kamehameha Schools for forestry and conservation, and Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, creating a large contiguous managed forest landscape,” it continues.

(For more background on the properties, see Environment Hawaiʻi’s October 2010 issue.)

Board Settles Fine For Violations On Duke Kahanamoku Beach

On May 26, the Land Board approved the settlement of a $65,000 fine it had imposed in May of 2021 for violations on Duke Kahanamoku Beach in Waikiki by Chris Sanger and Duke’s Lagoon, LLC.

Sanger and his company had been presetting chairs and storing equipment on the beach, and also conducting commercial activities there.

After some delays in settlement talks due to changes in Sanger’s and the state’s counsel, the DLNR’s Land Division recommended that the board settle the matter for $19,000.

Board member Kaiwi Yoon asked division administrator Russell Tsuji whether $65,000 was not a reasonable fine.

“I wouldn’t say that. We’re settling it … To get the $65,000, you have to file an action, go to court …,” Tsuji said.

Board chair Dawn Chang noted that the department will be seeking greater enforcement of illegal commercial activities. “If you are found in violation, it may be a basis to terminate all other … commercial use permits,” she said.

While the board approved the settlement, Yoon voted in opposition.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply