What is an act?

The question, posed in all seriousness, arose in the course of the state Land Use Commission’s deliberations relating to a 40-year-old planned residential development near Kailua-Kona, in West Hawaiʻi.

The developer, RCFC Kaloko Heights and related companies, had been seeking an extension of time – the sixth – to comply with conditions that needed to be met before the developer could ask for the 195-acre parcel intended for its second phase to be placed into the Urban land use district. Back in 1983, when the LUC approved the project, environmental regulations, affordable housing conditions, and laws respecting Native Hawaiian traditions were much less rigorous than they are today. The developer has argued that the legal and regulatory environment that existed in 1983 is the one that still rules today, regardless of the many changes that have occurred in the intervening four decades.

Commissioner Gary Okuda was wanting to know whether Alison Kato, the deputy attorney general representing the state’s Office of Planning and Sustainable Development, agreed with him that the Supreme Court’s decision in Ka Paʻakai o ka ʻĀina, handed down nearly a quarter century ago, would need to be complied with before the LUC could act on the developer’s time-extension request. The OPSD and the Planning Department of Hawaiʻi County had both signed on to a stipulation prepared by the developer that would have granted the time extension.

Earlier in the April 12 hearing, Okuda had quoted at length the Ka Paʻakai decision, which provides protections for Native Hawaiian rights and customs. He had questioned the developer’s attorney, William W.L. Yuen, whether the commission was bound by that decision in this case. “Isn’t it true that Ka Paʻakai says that the Land Use Commission has an affirmative duty to make the Ka Paʻakai inquiry before the Land Use Commission takes any type of action that might implicate resources protected by the Hawaiʻi State Constitution?” he asked.

The decision was not meant to be retrospective, Yuen replied, adding, “I don’t believe the action being requested at this time requires a re-analysis of the project.”

When it came time for the County of Hawaiʻi to present its position, Okuda posed the same question to the deputy corporation counsel representing the Planning Department, Jean Campbell.

“If we don’t have a Ka Paʻakai analysis here, doesn’t that place this decision at risk if we grant the relief requested by the petitioner?”

Campbell responded that “the spirit of the case is completely addressed” and that the LUC grant of a time extension “just allows the project to move ahead. At every future stage a Ka Paʻakai analysis will take place.”

Okuda pressed on: “Isn’t it true that that’s the point the court made? That the Land Use Commission could not delegate its duty to anybody else, so it’s the Land Use Commission that has to do the Ka Paʻakai analysis.”

“That’s your reading of the case,” Campbell said. “I agree with Mr. Yuen that it was not intended to be retroactive.”

Kato, representing OPSD, had to have known what was coming by the time she was asked to present her client’s position in support of the time extension to the commissioners.

Okuda did not disappoint.

“You heard, when I read from the Ka Paʻakai case, what the Supreme Court said, that agencies such as the Land Use Commission may not act without independently considering the effect of their actions on Hawaiian traditions and practices,” he said.

So, he continued, “my first question is, as that term ‘act’ – A C T – is used in that sentence, are we taking an action or acting as that word is used in the Ka Paʻakai case today? Is what we’re being asked to do is act?”

Kato seemed to be flummoxed. “I’m not sure I know the answer to that,” she replied.

Okuda pressed her: “What is the Office of Planning and Sustainable Development position on this? When we as a government agency take an action which affects land use as we’re being requested to do here today, is that an act or action as that term is used in the Ka Paʻakai case?”

“I don’t know the answer,” Kato said. “I have not researched this issue before.”

Okuda: “Based on your experience as a lawyer, what does the word act mean?”

Kato (puzzled): “What does the word mean?”

Okuda: “Aren’t we being asked to do something? A rule of statutory construction is you just use the plain meaning of the word. Or are you saying that what we are being asked to do isn’t really an action?”

Kato (struggling): “I mean, that has to be taken into context, with a review of the case —”

Okuda: “Are you aware of any legal authority that indicates that what we are being asked to do today is not an act as that word is used in the sentence I read from the Ka Paʻakai case?”

Kato: “I’m not.”

Times Change

The developer, which took over a project initiated by a Japanese firm, Y-O Limited Partnership, and Yuen argued that with respect to Ka Paʻakai and practically every other regulation and court decision made since 1983, the LUC’s hands were tied. By its actions back then, it had established the conditions of the Phase Two redistricting and, so long as the developer met them, the LUC could not impose any new requirements and would have to grant the requested redistricting.

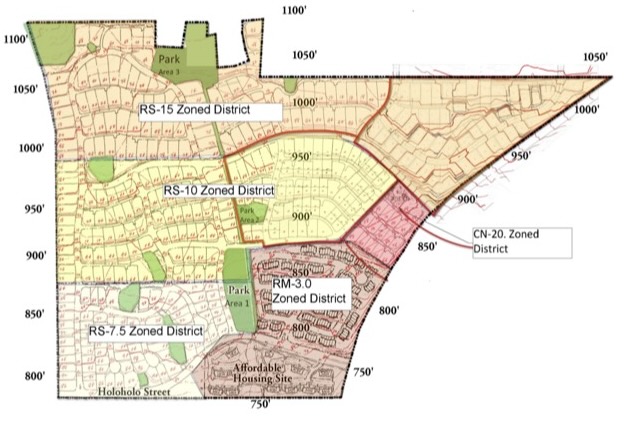

Under that 1983 decision, Y-O Limited Partnership was to have applied for redistricting of the Phase Two land by January 19, 1988. It was anticipated that by that time, the developer would have “made substantial completion of the onsite and offsite improvements,” including construction of a road connecting Queen Kaʻahumanu Highway to the belt road, Mamalahoa Highway, and partial completion of affordable housing requirements. The deadline was shifted to 1993, then 1998, then 2003, then 2013, then 2023.

Last November, Yuen submitted a motion to the LUC seeking to have it grant another 10-year extension to allow the developer to make “substantial completion” of the specified improvements. Yuen wrote that the commission had “pre-approved” the reclassification of the Phase Two land, with reclassification to be granted, no questions asked, when the developer made “a prima facie showing” of “substantial completion.”

The Office of Planning and Sustainable Development was initially agreeable to a time extension – not of 10 years, but of three. The office, wrote then-OPSD director Scott Glenn, was concerned “with the length of time that has passed since the original proposal was approved by the LUC. OPSD finds that another ten-year extension is unnecessary given the representations made by the petitioner that construction can begin once the wastewater line is in place, i.e., 2024. A shorter extension would give the LUC an opportunity to weigh in earlier, if the project is further delayed. …. Finally, OPSD recommends that the Phase II application comply with the state and county’s policies, regulations, and rules pertaining to land development, including, for example, but not limited [to], conformity with current planning documents and subdivision design standards.”

The one-paragraph stipulation that was ironed out among the OPSD, county, and developer, was submitted to the LUC one day before the hearing. It would give RCFC 10 years before it needs to seek redistricting of the Phase Two land, but it also would set a three-year time frame for completing 10 percent of the required affordable housing units built and offsite infrastructure.

Archaeology

Commissioners as well as members of the public who testified in person or who submitted written statements raised other concerns besides Ka Paʻakai issues.

Questions were raised as to the adequacy of the 2005 archaeological inventory survey, given that an AIS completed in 2019 for an 11-acre subset within the larger 213-acre Phase One parcel found several significant archaeological sites that had been overlooked in the earlier survey. The 11-acre parcel had been deeded to the Hawaiʻi Island Community Development Corporation, which is developing an affordable housing complex on the site to comply with affordable housing conditions in the 1983 decision.

Mark Meyer, speaking for the developer, was firm on this point: “There are kind of two different questions at hand. One of them is, are we going to redo the entire archaeological survey up front on the first phase? The other one is, are we going to be respectful of history out here, make sure we abide by the rules and regulations?

As to the first, he said, “we’re not in a position to re-do that entire process. I probably have never done a study of a large-scale property in my entire life that somebody couldn’t go, how do you know you got everything right? And the answer is probably never that we can get everything exactly right the first time.”

But, he continued, “what we are committed to is, there will be no – you find a burial out there and you say, ‘hey, let’s go move it to somewhere else.’ We are a very large firm with a lot at stake in both our reputation and the financial side of our company. We’re not going to risk that by doing some illegal activity.” (RCFC is indeed a large firm, but its reputation in Hawaiʻi – among the Land Use Commission and some Maui residents, at least – has perhaps been tarnished by its actions in relation to the Kehalani subdivision. For details, see the February 2021 edition of Environment Hawaiʻi.)

Chapter 343 Compliance

Commissioners spent a fair amount of time during the six-hour-long meeting questioning whether RCFC should have been or should now be required to comply with the state’s environmental disclosure law, Chapter 343, which would require preparing an environmental impact statement or environmental assessment.

“What would be the practical harm in doing this assessment, which would also take into account the concerns raised in public testimony about whether there could be potential impacts to surrounding areas?” Commissioner Okuda asked Meyer. “Just do that. And would there be any real practical delay in what you’re doing right now? Because you might be able to do that within the same period of time and nothing really slows down. And in the end you have an ironclad – or close to an ironclad – legal situation. Is there a practical problem in just trying to comply with Chapter 343?”

Meyer replied that the project was in compliance. “And,” he added, “there certainly is a huge practical problem” that would accompany preparation of an EA. “The process you go through to the point you’re entitled to build something … is a long and laborious process. We go through all this stuff … to then say, ‘let’s go back and start over again’ – just from a practical standpoint makes no sense.”

Okuda then quoted from a case decided in 2006 by the state Supreme Court, Sierra Club v. Office of Planning. At issue was whether the tunnelling under state roads to accommodate water and sewer lines supporting the development of the Koa Ridge project on Oʻahu required Chapter 343 compliance: “This is what the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court said, in connection with what triggers a Chapter 343 review: ‘Additionally, the project proposes the use of state lands inasmuch as the construction of the sewage and water transmission lines will require tunnelling beneath state highways.’ …

“This is the final sentence: ‘Accordingly, the project is an action that proposes the use of state land and an environmental assessment that addresses the environmental effects of the entire project is required.’

“So this,” Okuda continued, “is the language of the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court kinda staring us in the face with these eyeballs looking at us, telling us this is the law.”

Yuen, who represented one of the parties sued by the Sierra Club in that case, responded: “I believe that the environmental assessment that was prepared by HICDC covering the affordable housing project that also covered their sewer line adequately addressed the environmental assessments of the sewer line.”

“Yeah,” Okuda said, “but that’s not what the Supreme Court said in Sierra Club versus Office of Planning. It says the assessment has to cover the entire project.”

The environmental assessment for the affordable housing project, prepared in 2019, covers just the 11-acre affordable housing project immediately makai of the market-rate development.

“The HICDC property” – 11 acres – “is referred to throughout this EA as the Project Site,” that document states. It mentions the much larger Kaloko Heights market-rate development as one of several “reasonably foreseeable future” projects, along with other residential and light industrial projects near Hina Lani Street and housing in the Villages of Laʻiʻopua in Kealakehe. There is no further mention of impacts from the Kaloko Heights development, either in the brief discussion of projected wastewater generation (22,000 gallons per day from the affordable units) or in the traffic impact analysis report. Other planning documents not included or mentioned in the environmental assessment describe the sewer line as running along the south side of Hina Lani Street (requiring tunneling under that county roadway) and using county-owned rights-of-way along both Hina Lani and Ane Keohokālole Highway.

The 2019 agreement between the county Department of Environmental Management and RCFC allowing for wastewater to be treated at the Kealakehe sewage treatment plant states that the total wastewater generated at full build-out of Phases One and Two, as well as the affordable housing units, will be 364,000 gallons per day. In other words, the affordable housing wastewater flows mentioned in the environmental assessment are about 6 percent of the total flows expected to be generated by the Kaloko Heights development.

Under Chapter 343, environmental review is required for any action that uses state or county funds, including “any form of funding assistance … and use of state or county lands.”

A Denial

In his closing argument, Yuen continued to insist that to the extent the sewer line triggered Chapter 343, that had been taken care of in the 2019 environmental assessment done for the affordable housing parcel.

Now, he said, “the only question in the commissioners’ minds is whether the commission has to make a Ka Paʻakai determination on reclassification” of Phase Two.

“It’s our position that the commission in 1983, when it made the decision, was not bound by the Ka Paʻakai decision because the Ka Paʻakai decision followed after the 1983 decision. If the commission would like a Ka Paʻakai analysis, we would be prepared to say the petitioner would do one before coming to the commission in 2033 for approval of Phase Two. Other than that, we think the statutory scheme is, once the Land Use Commission makes a boundary redistricting determination, all the other studies, drainage, et cetera, in the remainder of Phase One and Phase Two would pass to the county.”

Commission chair Nancy Cabral then asked if any of the few members of the public in attendance wished to testify. Kimberly Crawford and Ruth Aloua, both of whom had testified in favor of placing more requirements on RCFC at the start of the hearing, weighed in once more, repeating their earlier concerns about impacts of the development on water and Hawaiian rights. Both mentioned the need for housing – but housing that the community could afford, and not another gated community that would not address the community’s needs.

Crawford informed the commissioners that she herself was living in a three-generational home, along with her parents and children. “Although we need housing for our people, 100 affordable housing units is barely putting a dent in this. Housing at the market rate isn’t affordable to even the people living here with good-paying jobs. Let’s be real.

“Are we really doing a service to our community by pushing forward this Phase Two or could we do better planning in 2023 than we did in 1983?”

Aloua was even more passionate on the need for housing that was affordable to the community.

“Do we need market homes that are going to be in a gated community?” she asked. “Who in this room can buy a house for a million dollars? That’s the market. That’s what we’re looking at…

“We have our kids living in cars in the Kmart parking lot. We have families living in cars, going to work, hoping they come home and all their mea [things] are still inside their cars parked on the side of the road. This project, it has to be looked at. It has to be reconsidered. We cannot continue to just expand, expand, and grow.”

Tom Yeh, an attorney who has worked for RCFC, then testified.

“RCFC wasn’t responsible for the last 40 years,” he said. “They’ve taken this project and brought it to the point where they can develop Phase One to get to Phase Two.

“You can make sure they comply with the conditions of Ka Paʻakai for Phase Two, comply with all those rules and regulations that they’re going to have to comply with either from a state or county level.”

Okuda asked Yeh, “If you’re saying a Ka Paʻakai analysis is going to have to be done at some point in time, why not just do it now and get the ball rolling? I mean, what is the harm? … What is the practical effect by just making sure these last couple of boxes are checked off so there is not something that happens like the Superferry case later on, where somebody pops out of the woodwork and just grenades this thing?”

“To the extent the applicant is required to follow Ka Paʻakai, it will follow it to the extent the law requires it,” Yeh replied.

Okuda then made a motion that the commission defer a decision on the time extension request “until a date that Mr. Yuen selects. … If you and your clients decide that this is a waste of time to deal with the issues raised today, fine. This will also give us time to consider and digest everything that was said today.”

His motion failed, prompting him to make a motion to deny the request.

“I’ve already stated my reasons why I don’t think we can move forward today,” Okuda said. There was the lack of compliance with Ka Paʻakai, he said. “Secondly, I believe Chapter 343 has been triggered.”

Other commissioners voiced their agreement.

Before the vote, Chair Cabral weighed in: “Denying [the request] at this time does not mean Phase Two disappears. It’s just in limbo until such time as Phase One continues to be developed. Then the petitioner could come back with another request to get Phase Two activated. Hearing the concerns of the community might help the petitioner.”

With that, the commission voted unanimously to deny the time extension.

Following the hearing, Environment Hawaiʻi asked Yuen how his client would respond to the denial. “No comment,” he replied, “as I don’t know what the owner intends to do. It certainly presents some problems, although the easy way out would be to develop agricultural lots.”

With the 193-acre Phase Two parcel zoned for five-acre Ag lots, there would probably be at most around 30 lots, given the need for roads, including the proposed extension of Kealakaʻa Street south from Hina Lani, and the inevitable set-asides for archaeological sites yet to be found and inventoried.

— Patricia Tummons

Leave a Reply