Commission Gives Hui Permit to Rebuild Waiheʻe ʻAuwai Destroyed by 2018 Flood

On February 18, 2018, a massive flood ripped away a 500-year-old ʻawuai that fed dozens of acres of loʻi kalo in North Waiheʻe in Central Maui. Although hundreds of people from across the island gathered in the days that followed to rebuild the stone ʻauwai so that farming could resume, they could only lift and carry so much by hand.

Kapuna Farms owner Mikiʻala Puaʻa-Freitas, who grew up at the foot of the ʻauwai and whose family has been maintaining it for generations, testified at the meeting last month of the state Commission on Water Resource Management that she’s now been growing only dryland kalo, which is “a whole other style of farming. When the flood happened, my world was turned upside down.”

Kalo farmer David Lengkeek, who used to sell to Aloha Poi in Wailuku, said he’s also been without water since the flood.

The native Hawaiian community group Hui o Nā Wai ʻEhā, which has spearheaded efforts to return flows into the streams and loʻi in the region, has been toiling for the past four years to change that. Three months ago, hui president Hōkūao Pellegrino filed a stream diversion works permit application with the Water Commission to allow for the construction of a more formidable ʻauwai and for the diversion of nearly 1.4 million gallons of water a day through it.

The hui has also been working with the state Historic Preservation Division to register the ʻauwai as a historic site.

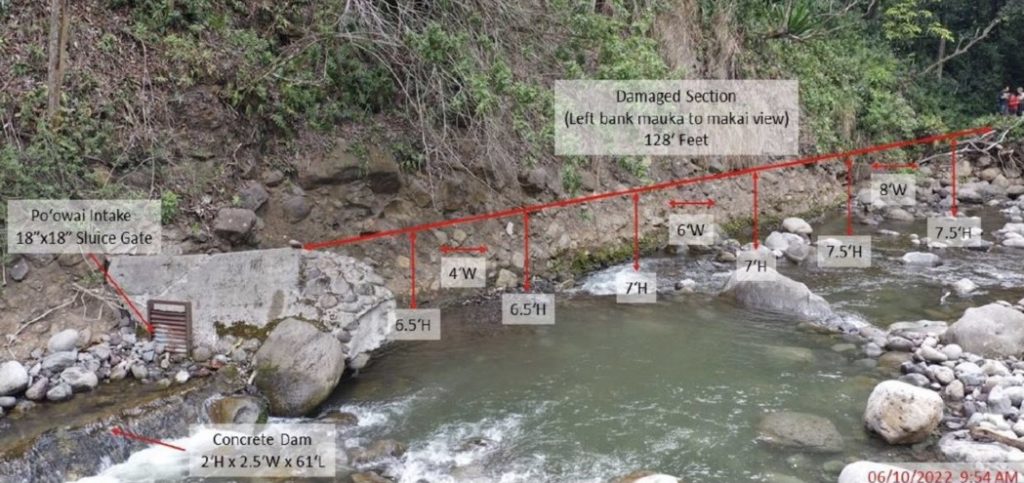

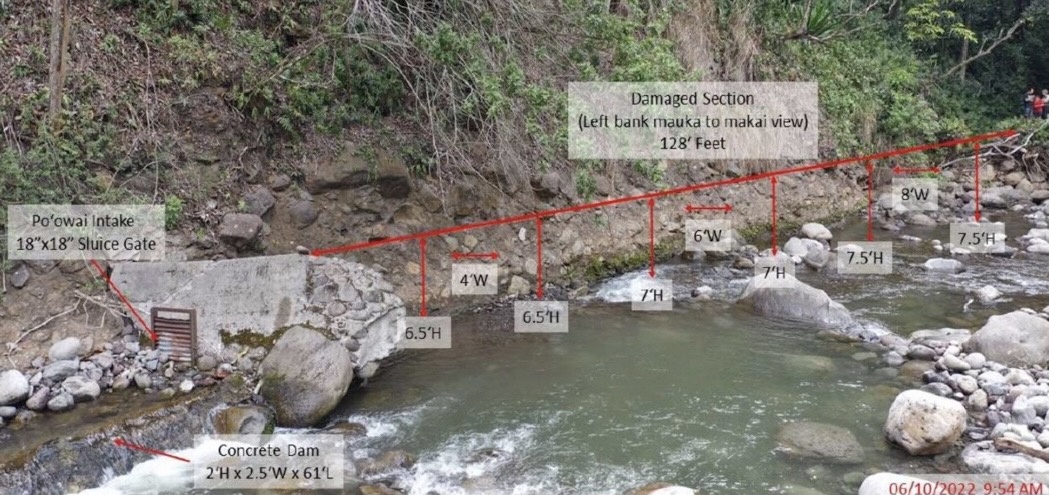

The application described a plan for Mahi Pono, LLC, the company working to expand diversified agriculture on former sugarcane lands in Central Maui, to use an excavator to dry stack a 128-foot long stone ʻauwai along the left bank of Waiheʻe River, on lands owned by Michael and Dana Pastula. The wall’s height would range between 6.5 and 7.5 feet; its width, between 4 and 8 feet.

The diverted water would feed nine acres occupied by farmers who hold surface water use permits granted by the commission in 2018.

At its September 20 meeting, the commission unanimously approved the permit.

Although community members had gotten some water to flow into the ʻauwai after the flood, “Waiheʻe is a very big, strong, powerful river. We need big pohaku to be stacked. That is the whole reason behind this permit. To set something up that will last for years to come,” Puaʻa-Freitas said. She added that it’s been difficult getting enough water to flow to the end of the ʻauwai.

The permit includes a condition that the hui notify the commission at least 48 hours before reconstructing any parts of the new wall that are damaged in the future

“If the rock wall must be relocated or enlarged, a request for determination shall be submitted to the Commission to determine if the reconstruction shall require a Stream Diversion Works Permit,” the condition adds.

Also, within four months, commission staff will work with Wailuku Water Company and North Waiheʻe ʻauwai permittees to address and resolve water distribution and delivery responsibilities in the appropriate proceedings. Currently, the permits incorrectly state that permittees receive their water via WWCʻs Spreckels Ditch.

Pellegrino noted that North Waiheʻe was the largest kalo growing area in the region before the flood and that the loss of the kuleana ʻauwai “caused great pain.” He thanked the landowners, commission and state historic preservation staff, hui members, and Mahi Pono’s director of water resources, Mark Vaught, for all of their work on the project.

“It truly was a collaborative process. It took us four years to get to this point,” Pellegrino said.

“This truly is a shining example and model of community initiative,” added Earthjustice attorney Isaac Moriwake, who represents the hui.

Like Pellegrino and Puaʻa-Freitas, he also recognized Mahi Pono, which he said had committed in a 2019 stipulation and agreement to give back to the Waiheʻe community and assist in the ʻauwai restoration. The company has been often accused by those advocating stream restoration as diverting far more water than it needs and wasting much of it.

Finally, he read testimony given to the Water Commission some 15 years ago by kalo farmer Stanley Faustino, who passed away in October 2018. Faustino, born in 1939, lived at the top of the kuleana ʻauwai, which he said fed 18 loʻi kalo on his property. But in the 1980s, that kuleana ditch was altered so it no longer connected to the loʻi, which then became polluted with weeds and infested with snails.

“Now, instead of our entire land covered in loʻi, there are only three,” he said.

He called for water to be restored to the loʻi, but not before it was restored to the river. The commission did order some water to be returned to the streams in 2010, which allowed some farms to grow, but the 2018 flood erased those gains made by those served by the ʻauwai.

“Rest in power, Uncle Stanley. It’s key we remember you when we bring it full circle,” Moriwake said.

Puaʻa-Freitas noted that the water diverted into the ʻauwai will be returned to the river. She also thanked everyone involved.

“This ʻauwai has been a beacon of strength for my community. … People on different sides of the pendulum came together. … I look forward to growing loʻi kalo once again and feeding my community,” she said,

Kely Rodrigues and his wife, Lindsey, hope to join her. They recently moved onto lands in Waiheʻe once owned by Kely’s late uncle, Mike Rodrigues, one of the water permittees served by the ʻauwai.

“He passed away waiting for the water, too,” Kely Rodriques told the commission. “I feel like it’s our time, our responsibility, to take over and carry his legacy and keep his vision alive for the next generations after us. While he was here, he constantly called and cried about his water not being there and how much he missed it.”

He plans to continue his uncle’s passion as a kalo farmer and “get that ʻauwai working so we can put our footprints in the loʻi and give back to what gave him so much joy and so much happiness while we here on earth. Our goal is to continue to make him happy while he’s watching us and making sure his life was never forgotten,” he said, adding, “We mahalo everybody here for listening to our little saying of what we had to say.”

Commissioner Neil Hannahs corrected him, “It’s not a little thing. It’s a powerful contribution to our work, so thank you for testifying.”

In 2018, the Water Commission issued its decision and order granting water use permits to new and existing users of waters from the Waiheʻe River, Waikapū Stream, Wailuku River, and Waiehu Stream. Since then, the commission has struggled with instances where permittees aren’t getting the water they’re entitled to.

“In our endless hours of deliberation on Nā Wai ʻEhā, we knew there would be challenges in implementation. This is the first Nā Wai ʻEhā item I’ve ever been on with support from everyone. For me there’s hope…,” commissioner Mike Buck said.

The commission unanimously approved Buck’s motion to approve the staff’s recommendation with a few amendments.

After the vote, Hannahs echoed Buck’s comments.

“Just as it takes stacking pohaku one by one to build a wall that fulfills a function, it’s going to take the stacking of collaborative projects, one by one, to build the kind of water community that I think will lead us to [accomplish] the visions that we have for the protection of this resource and fulfillment of its function to provide a way of life for people and so many public trust uses,” he said.

A Draft Plan to Address East Maui Water User Needs

In the near future, the Water Commission will be revisiting the interim instream flow standards (IIFS) for about two dozen East Maui streams that were the subject of a 2018 decision and order, as well as about a dozen that were not.

That order was the culmination of a 2001 petition filed by the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation and Maui Tomorrow and resulted in a significant amount of water, long diverted for sugarcane cultivation, being returned to streams that supported the growing of kalo and gathering by native Hawaiians.

Commission staff indicated in a briefing last month that that order is ripe for some amendments. What’s more, it made clear its intent to recommend amendments to the IIFS streams in the Huelo license area that were not included in the 2001 petition, but are the subject of a 2021 petition filed by the Sierra Club of Hawai’i.

Huelo is one of four license areas across which Alexander & Baldwin and East Maui Irrigation Company are allowed to divert tens of millions of gallons of water a day (mgd) via revocable permits from the state Board of Land and Natural Resources. It’s also the area from which the companies now draw the most water.

For decades, A&B and EMI have sought a long-term disposition for the water, which once served A&B subsidiary Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar’s fields in Central Maui. After the plantation closed in 2016, Mahi Pono, which now co-owns EMI with A&B, has been working toward developing diversified agriculture on the former sugar lands.

Although the Land Board has accepted A&B’s final environmental impact statement for a long-term water lease or license to be sold at public auction, a few obstacles need to be cleared before that can happen.

One of them is the reservation of water for use by the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, which is a public trust use. The DHHL’s development plans for Upcountry Maui would make it the largest Hawaiian homestead in the state. The agency also has plans to develop lands in Central Maui for commercial, light industrial, and agricultural use. The department has requested a little over 11 million gallons of water a day for its Pūlehunui (1.3 mgd) and Kēōkea-Waiohuli (9.8 mgd) lands.

To meet that request, as well as the needs of the county Department of Water Supply and Mahi Pono’s activities on fields designated as Important Agricultural Lands, the Water Commission must reassess how much water needs to remain in East Maui streams. And as staff with the Water Commission revealed during its recent briefing, all of this must be done while in the face of a consistent decline in flow.

Balancing Act

For years, the Sierra Club has argued that with the current IIFS for the Huelo streams, A&B and EMI are free to drain them dry while stream life suffers, as do residents living along the streams who rely on the water for farming and domestic uses, and residents and visitors who recreate in them.

It has fought against the Land Board, which continues to authorize the diversion of more water than Mahi Pono actually uses, although only on the conditions that all of its uses are reasonable and beneficial and that no water is wasted.

The Sierra Club is currently appealing to the state Supreme Court the Land Board’s most recent decision in a contested case over the companies’ permits. A decision by the Water Commission to set new IIFS to protect instream uses may go a long way toward resolving that conflict.

Commission staff have assessed the diversions in the Huelo area and instream uses, ranging from recreation, to ecosystem maintenance, to Hawaiian traditional and customary practices. They have also evaluated trends in rainfall and stream and ditch flows over the past several decades, as well as planned growth in the island’s center that will rely on diversions from East Maui.

Although East Maui receives the most rainfall on the island, CWRM hydrologist Ayron Strauch reported to the commission in August that mean annual rainfall has been decreasing, which has affected the base flows of some streams.

For example, median and low flows for Honopou Stream have dropped about 25 percent between the time periods of 1986-1996 and 2007-2016. For West Wailuaiki stream, median flows have declined 36 percent and low flows have declined 29 percent between those same periods.

The declines have been persistent and acute, and seasonal drought is becoming more intense and severe, Strauch said, adding, “Even in the middle of the wet season, this entire portion of the state is in some form of drought.”

This does not bode well for Upcountry Maui. The Department of Water Supply system there relies 80-90 percent on surface water from East Maui that runs through water treatment facilities at Olinda, Piiholo, and Kamole. Well water use is limited, as some are contaminated with legacy pesticides from old pineapple plantations.

Well water is also expensive compared to high-elevation surface water, as it requires booster pumps to push it uphill, Strauch said, noting that it costs hundreds of dollars per thousand gallons.

The Upcountry population is expected to increase slightly by 2035, and, based on the planned development in the region — including Makawao, Paia, and Haiku — an additional 7.3 mgd will be required to feed it.

With regard to Mahi Pono’s planned Central Maui expansion of diversified agriculture, including row and orchard crops, energy crops, and pasture, commission staff also estimated that the company will have a future surface water requirement of 41.3 to 49 mgd for its 20,000 or so acres.

Non-Mahi Pono agricultural uses will require 3.6-4.2 mgd, commission staff estimated.

Finally, Strauch noted the DHHL’s December 16, 2020, petition to reserve a little over 11 mgd of diverted East Maui stream water to serve the developments planned for Pūlehunui and Keokea-Waiohuli.

Based on commission staff’s assessment of ditch flows available following the 2018 IIFS decision and order, it found that only during median flows would there be enough water to meet all of the identified offstream needs. During times of low flow, there would be a deficit of nearly 49 mgd.

The staff’s report included a caveat that the estimates did not include the possibility that nearly 5 mgd could be provided by recycled water if and when the Kahului wastewater treatment facility is upgraded. Infrastructure to transmit the water to various users would have to be installed, as well.

The estimates also did not account for any future amendments to the IIFS for the Huelo streams.

Draft Proposal

On September 20, commission staff presented its draft recommendations to address the Sierra Club’s petition for the Huelo streams and the smaller portion of the DHHL’s requested reservation.

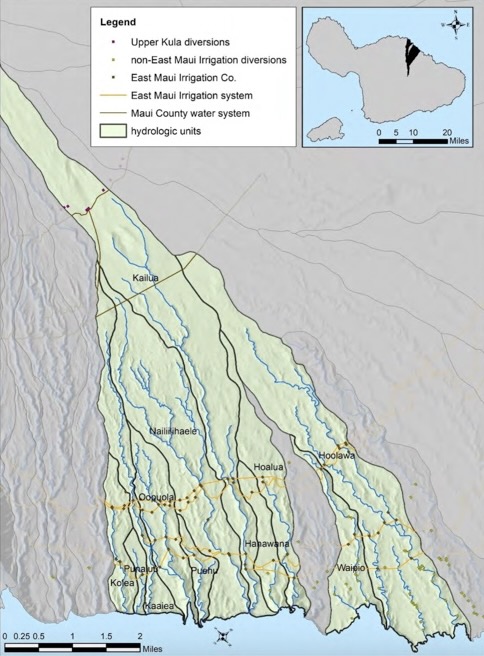

The commission staff made recommendations for 11 hydrologic units/streams: Hoʻolawa, Waipiʻo, Hoalua, Hanawana, Kailua, Nailiilihaele, Puehu, ʻOʻopuola, Kaʻaiea, Punaluʻu, and Kōlea.

For each stream, the staff report described its physical characteristics, biota, diversions, historic rankings, and what, if any, modifications to the diversion system need to be made to help protect instream and public trust uses.

For Punaluʻu Stream, which flows through a very small watershed and ends in a waterfall, staff recommended that its waters be used for non-instream uses and the diversions left as is. No native species were found in the stream during 15 site visits.

Staff made similar recommendations for the Puehu and Hoalua hydrologic units.

For the rest, staff recommended modifications to diversions to provide for better aquatic habitat, recreational uses and/or riparian uses.

Kōlea Stream, for example, runs through a relatively small hydrologic unit, has low flows, is diverted by three ditch systems, and terminates in a waterfall. Although no native species were found in the streams during 16 visits, the endangered damselfly Magalagrion pacificum was seen in East Kōlea Stream above Wailoa Ditch. The damselfly was previously thought to be restricted to East Wailuaiki stream.

Staff aimed to increase the length of stream habitat for the endangered species, while protecting it from non-native predator fish species, the Mexican molly, in particular.

“If we increase connectivity, they will prey on them. The goal is to expand their habitat without expanding habitat of invasive species. It’s tricky. … It’s a nuanced dance,” Strauch said.

To accomplish this, staff proposed modifying two diversion intakes “such that all flows up to 0.08 [cubic feet per second] remain in the stream without providing for connectivity.”

To increase connectivity for native aquatic species such as `o`opu in other streams, even if they terminate in waterfalls, staff sometimes recommended placing 18-inch plates across grate intakes.

In other cases, sometimes in addition to the installation of steel plates, staff recommended that diversions be abandoned, sealed, or otherwise modified so base flows in specified amounts could continue downstream.

Recognizing that these modifications will take years to complete, staff listed its top seven and committed to working with EMI over the next several months to develop an implementation schedule.

What’s Next?

Based on average flows of the Huelo streams between 1984 and 2013 (except for Hanehoi and Honopou, which were part of the 2018 decision and order), staff predicted that the proposed ditch system modifications along Wailoa Ditch — the uppermost of EMI’s ditches — will cause median stream flows to increase by 11.5 cfs (7.4 mgd). Low flows would increase by 2.9 cfs (1.87 mgd).

Modifications will also be made at the Spreckels, Center and Lowrie ditches so groundwater gains between Wailoa and Lowrie ditches remain in the streams.

In median flow situations, there’s 28 cfs (18 mgd) available for non-DHHL offstream uses; at low flows, only about 5.5 cfs (or 3.55 mgd) would be left, Strauch reported.

“There’s not enough water to meet the [full DHHL] reservation as requested,” he said, referring to the Kēōkea-Waiohuli project, which will include about 1,800 parcels on more than 6,000 acres in Upcountry.

The commission has plans to revisit the 2018 D&O for the 27 streams that were part of the 2001 petition to address some concerns. In that process, Strauch said, staff will try to carve out enough water for the Kēōkea-Waiohuli project.

“There’s more water available when we consider more streams,” he said.

Dr. Jonathan Scheuer, representing the DHHL, said the department was initially taken aback when it saw that its entire request was not being taken up that day, but Strauch’s explanation “helps a little bit.”

He questioned whether staff proposals to close some diversions at higher elevations would provide enough water for offstream needs at higher elevations — such as DHHL’s Kēōkea-Waiohuli development — to be met. “Upper elevation diversions are more valuable than lower elevation diversions,” he said.

The Sierra Club’s Lucienne deNaie suggested further modifications for some of the stream diversions to improve flow, but also testified that she was very glad the organization filed the petition for “very, very worthwhile streams … treasured by visitors and residents alike.”

Strauch said the commission can amend the IIFS as necessary in the future. “We have a lot more information now than we did for the 2018 D&O regarding habitat use for particular streams, community needs …”

Commission deputy director Kaleo Manuel requested that commissioners and members of the public relay to Strauch any comments or questions they have on the staff’s proposal.

Water Co. Seeks to Abandon Diversion Infrastructure

At its meeting last month, the Water Commission took up four requests by Wailuku Water Co. (WWC) to abandon ditch intakes that draw water from North Waiehu Stream, Wailuku River, and Waikapū Stream.

The commission approved three of those requests and deferred one.

WWC president Avery Chumbley testified that his company wanted to abandon its intake on North Waiehu stream because it was subject to “vandalism and community self-help.” He said WWC stopped using the intake in 2012.

Michele Ho‘opi‘i, whose family has drawn water from the North Waiehu Ditch for use on its kuleana land, opposed the request.

“For generations, we’ve grown and raised kalo. Mr. Chumbley states that there is no traditional and customary practices being done, which is not true.”

She explained that her family’s water use is not recognized in the commission’s 2018 decision and order for the Nā Wai ʻEha streams because her mother had chosen not to register her use or apply for a Water Use Permit.

Her mother has since passed and Hoʻopiʻi said that she is now the landowner and has applied for a permit.

Hōkūao Pellegrino, president of Hui o Nā Wai ʻEhā, said that there are other kuleana users without registered uses or permits and asked the commission to defer the matter “until we can spend a little more time … ensuring all kuleana users have access to kuleana water.”

Dean Uyeno, head of the commission’s stream protection and management branch, said it would be better not to delay the abandonment, since the intake was part of a “fairly leaky system.”

Chumbley agreed with Uyeno, adding that WWC is no longer the landowner on which a major portion of that ditch sits.

Earthjustice attorney Isaac Moriwake, who represents the hui, noted that a 2014 settlement called for WWC to provide water from the Waiheʻe Ditch, instead of the North Waiehu Ditch, for these kuleana properties.

“WWC was supposed to supply the Hoʻopiʻi’s with water from Waiheʻe Ditch. That is still outstanding. … This is highlighting the need to follow up with that,” he said.

Hoʻopiʻi said that she has no water coming through the property where she does subsistence farming, with her only source being what she trucks in.

“It has been a struggle and it is causing injury,” she said.

Commissioner Mike Buck said that when it finalized its D&O, the commission knew there were potential applicants who chose not to participate in the contested case hearing.

“We didn’t build in extra water, but knew people would come in,” he said. Still, he noted that abandoning the North Waiehu intake would not affect or deter anyone form receiving water from Waiheʻe in the future.

The commission approved the abandonment request, as well as those for the Kama Ditch intake on Wailuku River, and the Everett Ditch intake on Waikapū Stream.

When it came to the request to abandon the Reservoir 6 intake, also on Waikapū Stream, Chumbley argued against the commission’s recommendations regarding what WWC would be required to do.

Staff recommended that WWC remove an overhanging concrete lip at the downstream edge of a concrete apron that spans the stream, seal a tunnel at the control gate, and remove the gate infrastructure.

Chumbley said that being forced to break up the concrete apron to remove the lip could allow for more rocks and debris to flow past and collect around two supports for Honoapiʻilani Highway that sit within the stream. He said he had just recently seen Department of Transportation crews clearing out rubble around the posts.

Chumbley suggested that the concrete be left alone, especially since bringing heavy machinery in the stream could do more harm than good.

There was some discussion about whether or how to remove steel rails embedded in the concrete, and whether if they are left in place there should be some signage to warn people who may be walking in the stream. Chumbley argued that the rails should be left in place.

Uyeno noted that his staff had not consulted with the DOT about the potential effects the concrete removal would have on the highway and said it would be a good idea to do so.

The commission voted to defer the matter to give staff time to work through the issues that had been raised.

—Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply