The state and homeowners who built a seawall on Oʻahu’s Sunset Beach in 2017 without any government approvals head into settlement talks this month, following a 1st Circuit Court ruling on October 21 granting in part and denying in part the state’s motion for partial summary judgement.

One of the ruling’s more significant findings: Seawalls cannot, by themselves, be used to determine the boundary separating private property from the state’s coastal lands.

That boundary, also known as the Ashford boundary, is where the highest wash of the waves reaches, usually indicated by the edge of vegetation or the line of debris.

The state’s Coastal Zone Management Act states that “certified” shorelines, which are used to determine shoreline setbacks, shall not be valid for more than a year, “except where the shoreline is fixed by artificial structures that have been approved by appropriate government agencies [emphasis added] and for which engineering drawings exist to locate the interface between the shoreline and the structure.”

The fact that contractors for James and Denise O’Shea built their 13-foot-high seawall without any city or state approvals means that they can’t use the CZMA to argue that their property line extends to the wall’s base. Depending on the outcome of their settlement meeting on November 9, they may be required to remove the wall or, at the very least, be penalized for their unauthorized work in the county setback area.

“At minimum, it appears a variance was required,” Environmental Court Judge Jeffrey Crabtree wrote in his order.

The O’Sheas made clear in their filings that they believe a removal order would be unacceptable.

“If the O’Sheas’ wall is removed and the state is correct that the ocean will immediately move mauka into the O’Shea property, what will happen next? The O’Shea’s remaining yard and slab-on-grade home will be undermined. Again assuming the state is correct, the ocean will immediately flank around the existing [neighboring] Mooney wall and Oberlohr wall, causing the failure of each,” their attorneys state in a brief.

The state, however, argued that despite multiple warnings and a pending lawsuit brought by the state, the O’Sheas “disregarded the property rights of the state, ‘took a chance,’ and completed the wall. Landowners such as the defendants cannot simply erect immense, expensive structures on public land and then complain of the hardships they would suffer in removing their encroachments.”

If the parties fail to settle the case, a jury waived trial has been scheduled to begin on January 18.

Emergency

On September 3, 2017, an old seawall that protected the O’Sheas’ Sunset Beach home collapsed, but not from being undermined by ocean swells.

The O’Sheas argue that their then-neighbor, Rupert Oberlohr, broke the wall when he affixed and tightened cables to parts of the wall fronting his home in an attempt to secure it.

The wall, which spanned multiple properties, appears to have been built in the 1950s. The O’Sheas claim the state built it. The state denies this.

In any case, immediately after the collapse, the O’Sheas began building a new seawall without any authorization from the City and County of Honolulu — which has jurisdiction over activities within the shoreline setback area — or the state Department or Board of Land and Natural Resources — which control activities on public beaches.

After they ignored warnings from the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands to stop work on the wall, the state sought and received a temporary restraining order on September 22, which expired on October 2.

The city also issued the O’Sheas a notice of violation on October 6 for conducting major repairs to an existing seawall in the shoreline setback area without first obtaining a shoreline setback variance and for doing structural work without first obtaining a building permit. The city ordered the O’Sheas to restore the area within 30 days.

Instead, the O’Sheas completed the wall in October, according to OCCL administrator Sam Lemmo.

On October 13, 2017, the Board of Land and Natural Resources discussed a proposal from the OCCL to fine the couple $75,000 for the illegal construction within the Conservation District.

The couple’s attorney, Greg Kugle, asked for a contested case hearing before the board could vote on the matter. That case has been stayed pending the outcome of the lawsuit stemming from the temporary restraining order the state had obtained.

“The state for unexplained reasons allowed the TRO to expire, and the O’Sheas then went ahead and built their new 13-foot high seawall,” Crabtree wrote in his September 14 ruling.

The O’Sheas argue that the seawall was built entirely on their property, which negates the need for any state approvals. The state, however, says that the wall lies within the high wash of the waves and, therefore, encroaches on public land.

In its motion for partial summary judgment, the state pointed out that the only support the O’Sheas offered as proof that the wall was built on their property were shoreline certifications from 1988.

Ashford Boundary

In its motion, the state asked the court to grant a mandatory injunction ordering the removal of the seawall. If the court chose not to grant the injunction, the state asked instead for a declaratory judgment finding that the seawall encroached on state land.

In their briefs, attorneys for the O’Sheas argued that the Ashford boundary and the shoreline as determined by the Land Board in accordance with the CZMA are the same. They also argued that the Land Board alone has the authority to designate where the shoreline is.

They argued that the language of the act incorporates the objective of the Ashford boundary line, “indicating that the determination of the shoreline pursuant to its terms serves a much larger purpose than just defining the shoreline setback area.”

They added that the act “has entirely subsumed, and also supplemented, the definition of the Ashford boundary line, indicating an intent for the BLNR-determined shoreline to replace the Ashford boundary line.”

Under the act, a certified shoreline is determined to be at the highest wash of the waves — excluding those caused by storm or seismic activity — during high tide and in the season when the waves are highest.

“While the CZMA allows for the shoreline to be fixed by an approved and privately-owned structure, the common law makes no such accommodations in regard to the Ashford boundary line. Thus, a court’s determination of the Ashford boundary line could be considerably further mauka than a shoreline that is fixed by an approved and privately-owned structure. Such a determination by a court would leave the privately-owned structure firmly within the boundaries of public land and subject to trespass proceedings brought by the state, despite the structure’s approval by relevant government agencies,” they wrote, calling this an “absurdity.”

Absurd or not, the Land Board has for years been requiring easements from landowners whose seawalls have been found through the shoreline certification process to be makai of the state property line. The state has explained in the past that the Ashford shoreline and the certified shoreline are closely related, but not the same. However, the certified shoreline does serve as a proxy for the property boundary line.

In August 2017, shortly before the O’Sheas’ seawall failed, even Land Board chair and DLNR director Suzanne Case asked the Department of the Attorney General for clarification on aspects of the state’s ownership of coastal lands, specifically with regard to the board’s practice of requiring easements for legally built structures that have come to encroach on state land.

In its December 2017 response, deputy attorney general William Wynhoff assured Case that the state owns additional land when the shoreline moves mauka, that it is not a taking of private land, and that the Land Board can and should charge market rent for any easements obtained to resolve encroachments.

However, in a footnote, he also admitted, “Shoreline and ownership lines are the same where the shoreline is not affected by structures. No Hawaiʻi case or statute address the question of where the ownership line is when the shoreline is affected by a seawall or other man-made structure.”

Although the O’Shea case doesn’t resolve the question of where the shoreline is in those instances, it does speak to where it isn’t.

When Judge Crabtree signed the order finalizing a ruling he made on September 14, he largely adopted the position the state took in its briefs on whether or not an illegal seawall can artificially fix the shoreline. However, Crabtree expanded that position to include not just illegal structures, but all artificial structures.

As the state did, Crabtree cited a 2014 Hawaiʻi Supreme Court decision (Diamond v. Dobbin) that determined that an artificially enhanced vegetation line cannot “usually” set the Ashford boundary. “[N]either can an artificial seawall usually set the Ashford boundary in and of itself,” he wrote.

Crabtree stated that under the CZMA, an artificial structure may be used in a shoreline determination. However, he also noted in his September 14 ruling that the act’s shoreline determination for county setback purposes was not the same “legal event” as determining the highest wash of the waves to establish a property boundary.

And because the certified shoreline under the CZMA and the Ashford boundary are not, as he put it, the same legal event, Crabtree also ruled that the court does have the authority to establish the Ashford boundary.

In his September 14 ruling, he noted that the Ashford boundary could be decided in Land Court, but a trial court is not obliged to have the Land Court make that determination.

Storm Waves

While Crabtree adopted many of the state’s arguments in his ruling, he held back on ruling whether or not the O’Sheas’ seawall encroached onto state land.

Although Crabtree found that the certified shoreline under the CZMA and the Ashford boundary are not the same legal event, they are defined in the same way.

Crabtree determined that the evidence presented showed that waves do hit the O’Sheas’ seawall during the winter, which is when the highest wash of the waves occur on O’ahu’s North Shore.

However, he declined to rule on whether or not those waves are storm waves.

If they are not storm waves, then the seawall encroaches onto state land, he wrote, adding, “[I]f the waves are hitting the seawall, the highest wash is mauka of the seawall.”

The state had introduced a number of exhibits, including video taken in the years following the seawall’s construction, showing waves hitting the wall.

In one exhibit offered by OCCL administrator Sam Lemmo, for example, video taken on October 8, 2019, showed waves hitting the wall before the tide and before expected swells were forecasted to peak.

For all but one of these state exhibits, the O’Sheas have contended that they show waves are washing up against a neighbor’s wall, not theirs.

With regard to the state’s Exhibit 18, however, there is no dispute that drone footage taken by Dr. Shellie Habel of the University of Hawai`i’s Sea Grant program shows waves hitting the O’Shea’s seawall on December 2, 2020. There is, however, a dispute over whether those waves were caused by a storm.

Habel and the state’s attorneys offered evidence showing that neither the Central Pacific Hurricane Center and the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center reported any storms or tsunamis that might have caused the waves on December 2.

Even so, Crabtree explained that he could not, based on the information on the websites of those agencies, find that the wave in Exhibit 18 was not due to a storm. “The court would have to draw inferences from the exhibits. The court is not allowed to make such inferences against the non-moving party on summary judgment,” he wrote.

He added that he was not aware of any requirement that storm waves come from a named storm and also shot down the state’s position that storm waves had to come from a storm visible from shore.

“[T]he argument seems counter-intuitive, since it is well-known that storms cause ocean waves from hundreds and even thousands of miles away,” he wrote.

On this point, Crabtree referenced the declaration of retired University of Hawaiʻi oceanographer Patrick Caldwell, submitted on behalf of the O’Sheas. Attached to Caldwell’s declaration was his NOAA surf forecast for December 2, 2020, the day Habel’s video was taken. That forecast noted that a “hurricane-force” system from the far northwest Pacific had “occluded near 50N, 165W 11/30 with top winds near storm-force. This is the source for the surf arriving locally 12/2.”

“Given what is at stake in this case (on both sides), and given the apparent disagreement between Dr. Habel and Mr. Caldwell’s conclusions, the court declines to make a dispositive ruling at this time, on this record, that the wave in Exhibit 18 is not due to a storm,” Crabtree wrote.

Stalled Enforcement

Whether any portion of the O’Shea’s seawall sits on public land remains to be seen. If any of it lies within their shoreline setback area, the City and County of Honolulu would have a say in the fate of the wall.

The Notice of Violation the city issued in October 2017 gave the O’Sheas 30 days to restore the area. Otherwise it would issue a Notice of Order imposing civil fines. There is no indication that it ever did that.

What’s more, on September 26, 2019, the city actually granted the O’Sheas’ contractor, Uaitemata Ungounga, a building permit for what he claimed were repairs to the O’Sheas’ existing 13-foot high seawall. The work was expected to cost $25,000, according to the permit.

The new seawall had already been built by then.

Shortly after issuing the permit, the city realized its error and revoked it on October 9, 2019.

The city stated in its revocation notice that incorrect information had been provided to obtain the permit. The city gave the O’Sheas 180 days to remove or demolish the structure, revise the building permit, or obtain a new permit to complete the work in accordance with current laws.

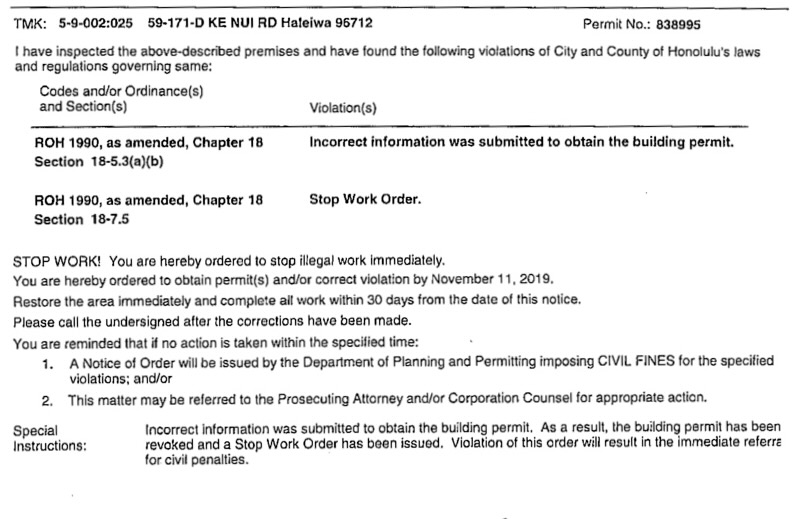

Also on October 9, the city issued a second notice of violation to the O’Sheas, along with Ungounga and IMH Engineering. They were cited for providing incorrect information to obtain a building permit and for violating the city’s 2017 stop work order.

Similar to the 2017 NOV, the notice ordered them to stop work immediately (although it seems to have already been completed), obtain permits or correct the violation by November 11, 2019, and complete restoration of the area within 30 days.

Again, they were warned that the city would issue a Notice of Order imposing fines, but, again, it does not appear that this occurred. The city Department of Planning and Permitting’s online list of outstanding notices of order does not include the O’Sheas’ property.

Under the city’s ordinances, a Notice of Order may include fines of up to $2,000 for each day a violation persists.

According to a February 26, 2021 declaration for the state by Jocelyn Gervacio Godoy, the DPP’s custodian of records, no applications had been submitted for either a shoreline setback variance or a building permit for the seawall.

— Teresa Dawson

Melissa Spectre

The house in the photograph you used in this article is NOT the O’Shea’s house.