When the virtual meeting of the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council opened on September 21, chair Archie Soliai led off with a Christian prayer.

Although the council is a federal body, no one objected. Rather, participants on the WebEx screen duly bowed their heads as Soliai asked his lord to guide the council’s deliberations over the next three days.

With that, the 187th meeting of the council was launched.

Turtles

One of the first items on the council’s agenda was the report of its longtime executive director, Kitty Simonds. Simonds was especially happy to report what she apparently sees as an increase in the population of honu, the green sea turtle.

“I point you to the PIFSC report,” she said, referring to the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, an arm of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “How the numbers have increased – and, actually, I’ll quote, ‘These numbers for basking turtles far exceed numbers seen during previous monitoring seasons.’”

The PIFSC report did note that numbers of basking turtles at Tern Island, in the French Frigate Shoals, “far exceed numbers seen during previous monitoring seasons at that site.” What Simonds did not mention is the fact that one of the primary turtle haul-outs at French Frigate Shoals, East Island, practically disappeared after Hurricane Walaka tore through the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in 2018, resulting in greater use by the turtles of Tern.

“Monitoring includes what’s happening around main Hawaiian islands,” Simonds continued. “The nesting season is still ongoing, with 150 documented nesting events around O‘ahu’s north shore, Moloka‘i, Maui, Kaua‘i.”

When Mike Seki, PIFSC director, made his presentation, he was not as sanguine as Simonds about the recovery of the turtle in Hawai‘i, a distinct population segment listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act. Seki mentioned that the loss of habitat in French Frigate Shoals could be why increased nesting is being seen in the main islands.

Or, as the Science Center’s report states, the nesting in the main islands, “coupled with the major alteration of one of the primary remaining nesting habitats in the NWHIs (East Island), as a result of hurricane Walaka in 2018, have raised the possibility that the MHI may represent increasingly important nesting habitat for green turtles. The islands may offer protection and buffer against threats such as nesting beach loss due to climate change.”

A week earlier, when the council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee was discussing the Science Center’s report, Simonds commented that the situation “looks like it’s not as dire as we all thought it was when the hurricane happened.”

“More kau kau!” she added.

The full council discussion of the status of sea turtles, which usually would take place in the section of the agenda dealing with protected species, was instead shifted to the last day of the three-day meeting.

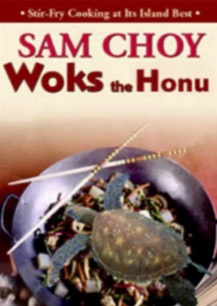

The power-point presentation that led off the council’s deliberations was prepared by council staff and highlighted what it described as the cultural value of the turtle to Native Hawaiians. One slide included a photo-shopped cover of a cookbook by Sam Choy, showing a turtle in a wok.

Josh DeMello, the staffer narrating the presentation, stated that the Hawaiian elders most knowledgeable about how to use the honu – for food and medicinal and cultural purposes – were dying off. “We continue to hear from fishers complaining that kupuna are passing on. We need to be able to pass on knowledge, ecological knowledge … There’s a cultural disconnect,” he said.

Council members from Guam, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa wholeheartedly embraced the idea of cultural take of the turtles.

David Sakoda of the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources and a representative of Suzanne Case, head of the DLNR, chimed in on the subject as well. “It’s important to keep exploring cultural take permits,” he said. “I was in Ha‘ena and talked to an auntie up there. Her grandfather had turtle oil, and when she had a burn, her grandfather applied turtle oil to it. Now you can’t see the scar.

“Lots of medicinal uses are being lost. Cultural practices need to be maintained and rediscovered,” he said.

Matt Ramsey, director of the Hawai‘i program of Conservation International and a newly appointed council member for Hawai‘i, also supported the work. “Any management change will take a while,” he said. “In the meantime, we can’t wait to start that documentation process. We have to interview kupuna, elders. It’s extremely important. We can’t wait too long for that.”

It fell to Mike Tosatto, director of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Pacific Islands Regional Office (PIRO), to inject a discouraging word.

“I want to make sure the council’s expectations are set properly,” he said. The report presented to the council is “an acceptable report, but, to be clear, this is not a fishery resource. It is not under the purview of this fishery management council. The role of the council must be measured and smartly executed. There are boundaries for this council and council staff. … This is a turtle that’s subject to an international agreement the United States has signed.”

Any permit to allow turtle takes, he noted, can be considered “only when it’s in the best interest of the conservation of the species. So our preliminary analysis of this species, including the disappearing islands of French Frigate Shoals, its principal habitat nesting area, makes it a very hard case to see how additional take would benefit conservation.”

Nonetheless, council staff proposed a motion for members to consider, directing staff “to continue working with NMFS to determine the feasibility of a cultural take of green sea turtles for Hawai‘i.” A second motion directed staff “to document the history and tradition of green sea turtle harvest in Hawai‘i to include in future management, including a video capturing interviews of community members that previously held subsistence permits for honu, and/or otherwise hold strong familial cultural connections with the harvest and use of honu.”

Again, Tosatto cast cold water on the proposal. “This is work directly supportive of a petition to NMFS,” he noted. And therefore it would not be within activities supported by the council’s grant, and therefore could not be conducted by staff.”

Simonds proposed a different approach. “Of course, we will speak to [General Counsel] about this document, but you do know that years ago, the council developed – but never finished – a management plan for the honu and we are allowed to develop a management plan for the honu. The only species we can’t develop management plans for are birds and marine mammals … I could say we are developing a management plan for honu and we need to do this. We will have a discussion with GC.”

The motion passed.

False Killer Whales

The capture of false killer whales by Hawai‘i longliners is one of the biggest concerns of the owners and operators of the 148 vessels currently holding permits to operate out of Honolulu harbor. If four false killer whales are observed caught within the U.S. exclusive economic zone, and NMFS determines that the injuries are serious or likely to result in the animal’s death, then a large swath of the ocean south of the Main Hawaiian Islands known as the Southern Exclusion Zone (SEZ) is closed to the fleet for at least the remainder of the year.

As of the end of August, the deep-set (tuna-targeting) longliners on which observers had been placed had caught 12 false killer whales, three of them inside the EEZ. Two were determined to be serious and one was a mortality. At the Wespac meeting, Diana Kramer, with the NMFS PIRO Office of Protected Resources, called out one piece of good news in her otherwise grim report: in one of the hookings last June, the hook straightened, allowing the animal to swim away. A NMFS-sponsored study of the effects of weak hooks, in the works for several years, has finally been completed, Kramer said, and will be presented to the False Killer Whale Take Reduction Team (TRT) by the end of this month.

But Kramer also noted that a thirteenth hooking had been observed more recently. Details on that interaction – whether it was inside or outside the EEZ, whether it was classified as an M&SI or not – were not available at that time.

If that interaction is judged to have resulted in a mortality or serious injury, then it would seem as though the SEZ closure would be triggered.

Getting rid of the threat of that closure, which for most of the last decade has been a critical part of the take reduction plan developed under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, has been a paramount objective of the longliners for years.

Last year, a small subset of members of the council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee undertook a review of the TRT’s false killer whale recovery plan, its metrics, its mitigation measures, and its results. Members of the group were the SSC chair, attorney Jim Lynch, Queensland fisheries scientist Milani Chaloupka, retired professor of social sciences Craig Severance, and Askua Ishikawa, a council staffer.

At the SSC’s June meeting, a draft paper that the sub-group put together was shared and discussed by members of the SSC, a committee that is established under the federal Magnuson-Stevens Act to advise the council on scientific matters. Its members are selected by the council and generally embrace approaches that favor expansion of fishing opportunities. The draft was not available for public review at that time.

At the September SSC meeting, held the week before the full council met, the draft paper was still not available to the public, but again it was discussed at length by the SSC.

Lynch led the discussion. “We wanted to create a marker, a bright line in the sand as to what the SSC believes should occur with respect to false killer whales,” he said, adding that the regulations “had a substantial impact on the operation of longline fisheries.”

The paper was highly critical of the metric known as Potential Biological Removal that is required by the MMPA to be used in determining allowable levels of harm.

“Blindly relying on PBR is not the best approach,” Lynch said. “The agency” — NMFS – “may feel it is constrained by law, but better tools should be considered and used to develop appropriate take reduction measures.”

The group also recommended that the SSC be included on the Take Reduction Team, “so a more rigorous scientific approach can be used,” Lynch said.

The final recommendation in the paper was for the council to undertake a study to assess the economic impacts of mitigation measures, he noted.

Lynch then asked the full committee to adopt the recommendations in the sub-group’s report, “so we can forward these as recommendations to the council.”

“Any objections to indicating the SSC adopts these recommendations as their own?” he then asked.

The group responded with silence, which Lynch then deemed to be approval.

When the full council met, Lynch described the subgroup’s work and the recommendations it had arrived at. Council members’ comments were enthusiastic.

Again, it fell to Tosatto to throw a bit of cold water on the discussion.

“I want to make sure the council, under the Magnuson Stevens Act, knows it has a charge to reduce bycatch of all species and reduce interactions with protected species. This is where there is an overlap with the mandates of the Marine Mammal Protection Act. I need to be cautionary about the SSC, to make sure they focus on efforts that meet the council’s broad charge to reduce bycatch and appropriately support the council’s role as one of the many members of the Take Reduction Team…

“Some of the things the SSC recommends are on target, but a couple of things are not necessary to MSA management and are not capable of entering into the MMPA construct, which requires us to consider PBR. … We have a scientific adviser, and it is not the SSC,” he said, noting that under the MMPA, the Take Reduction Team is advised by the Pacific Review Group.

Notwithstanding Tosatto’s caution, the full council adopted all the recommendations in the SSC report.

Transparency Issues

Wespac lags behind other fishery management councils when it comes to transparency. For years, documents distributed to council members that concern budgetary matters and other administrative concerns have been withheld from the public.

The September meeting was no exception. The council’s Executive Committee met the day before the full council meeting was opened. The agenda had no links to any of the documents provided to council members that related to financial reports or administrative matters.

In the public WebEx meeting, however, those documents were discussed. With regard to the financial reports, Simonds noted that the council “is on track to spend all of our money.”

Simonds called on her staff to elaborate on other aspects of the financial report, including funds spent on coral reef studies, ecosystem modeling, nenue research, shark depredation in the Mariana islands, tori lines, and other issues.

Then, suddenly, Soliai announced that this was the end of the public meeting: “We have a closed session after our agenda.” Simonds elaborated, “This part of the meeting is over. We will go into closed session.” Abruptly, members of the public were removed from the WebEx session.

Tosatto was asked about the closed session, which was not in the Federal Register notice of the meeting. In reply, he said that the NOAA general counsel “was consulted in advance by the council executive director [Simonds] about the potential to close a portion of this meeting so the committee can discuss ‘employment or other administrative matters.’”

He then referred to a portion of the Magnuson Stevens Act that allows the council to, “without the notice required” elsewhere, “briefly close a portion of a meeting to discuss employment or other internal administrative matters.”

Other councils are not nearly as cagey when it comes to financial matters. The public agenda for the September meeting of the Pacific Fishery Management Council, for example, links to a detailed financial report made by its executive director. The Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council discloses the stipends paid to members of its Scientific and Statistical Committee ($300 a day), and also includes the most recent audit of its books.

Wespac members finally got around to the agenda item relating to financial and administrative concerns, in the final hour of the last day of the meeting. “Council members have had the first two documents” – financial and administrative reports – “for more than a week,” Simonds said. “Any comments?”

There were none. The council then, without objection, adopted a motion to “endorse the 1875th council meeting financial and administrative reports as provided by staff.”

Soon after that, chair Soliai closed the meeting with a prayer, solemnly observed by all.

— Patricia Tummons

Leave a Reply