“It’s pretty intense,” says state toxicologist Dr. Diana Felton.

With rising seas and more frequent severe storms expected as a result of the climate crisis, she and Department of Health colleague Dr. Iris van der Zander warn of the increased potential for lead, arsenic and other contaminants at hundreds of polluted sites throughout the state to leach into coastal waters, into drinking water sources, and to spread throughout neighborhoods during floods.

And in areas such as Honolulu Harbor, where the ground has been saturated with petroleum after years of pipeline and fuel storage tank leaks, they say the infiltration of seawater, groundwater, or stormwater may spur the production of explosive and noxious gases.

A June 21 memorandum on climate changes and chemical contamination authored by Felton and van der Zander details these threats and makes several preliminary recommendations on what to do about them.

It notes that many of the 1,000 or so contaminated sites that HEER monitors and regulates are in low-lying areas and along shorelines. “Common chemical classes contaminating shoreline areas include petroleum constituents, heavy metals, solvents, pesticides, and persistent organic pollutants,” the memo states.

These sites are not usually remediated and instead are simply capped and left alone. But that approach may be outdated, the authors suggest.

“These strategies have historically been viewed in the context of a static environment. The increasing impacts from climate change and sea level rise including more frequent flooding, accelerated erosion, and related disruption of contaminated lands due to sea level rise, ground water inundation, and an increase in storms and heavy rain events require an equal progression in the manner in which risk is evaluated and mitigated for these types of sites. Of particular concern are large, current or former industrial sites in coastal areas that are known to be heavily contaminated and are at high risk of climate change-related impacts. This includes many harbors, airports, bulk fuel terminals and former landfills in the islands,” the memo states.

Explosive Gases

At these contaminated sites, “[a]s long as the subsurface is sufficiently aerated and enough oxygen is present, methane oxidizing bacteria can degrade petroleum to CO2. Unfortunately, as these areas become inundated from sea level rise, groundwater inundation or flooding, the oxygen supply decreases, leading to enhanced production of methane,” the memo states.

Monitoring data from wells at Honolulu Harbor have shown that subsurface methane levels often spike during high tides and heavy rains.

The memo notes that the concrete surfaces in the area and the installation of plastic liners at active fuel terminals have hampered oxygen circulation to the underground pollutants.

“Methane can build up in areas under pavement and move along utilities or utility corridors, into confined spaces and accumulate in other subterranean pockets, creating a significant explosive hazard for utility workers and construction crews,” it states, adding that methane vapors appear to be “enhanced during low atmospheric (barometric) pressures. This indicates a heightened risk of high methane concentrations during storm events.”

Felton says that the actual risk increased methane production poses is still being determined, since the gas would have to be concentrated and exposed to a spark to cause an explosion.

In addition to methane, the memo also notes that sea water inundation of petroleum contaminated soil will likely increase production of toxic, and flammable, hydrogen sulfide gas.

“Hydrogen sulfide gas and methane vapors can migrate laterally and vertically and potentially intrude into buildings, creating indoor air quality concerns and flammability/explosive hazards,” it states.

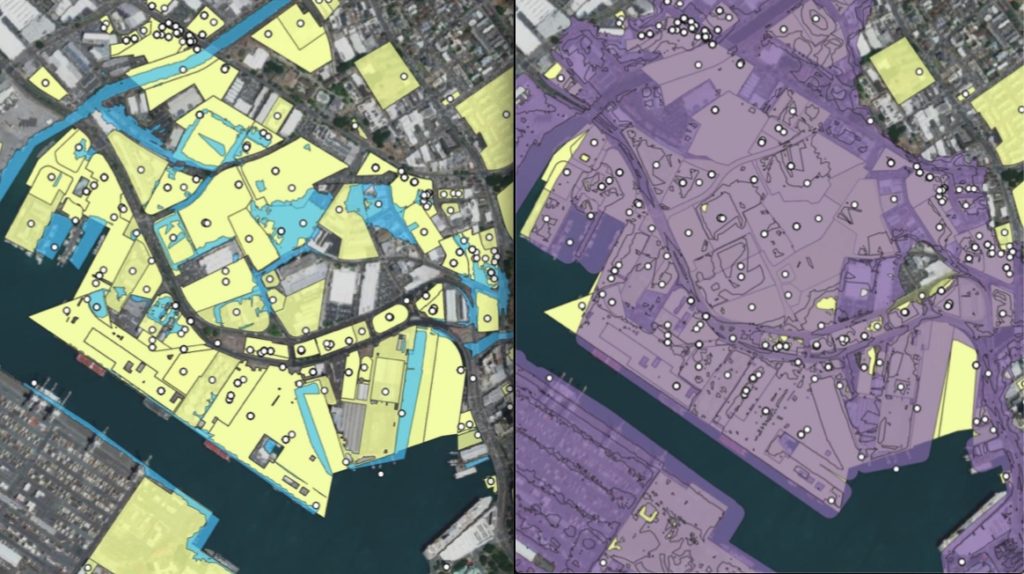

The memo, the content of which was shared at the Hawai‘i Climate Commission meeting last month, showed that there are about 100 HEER-regulated sites in and around Honolulu Harbor.

Only about a dozen of them would fall directly within inundation areas if sea level were to rise 3.2 feet. But add a 100-year flood-type event on top of that, and all of the sites would be vulnerable.

Chemical Catastrophe

As Hakai magazine reported in an article published last November, the chemical contamination in certain parts of downtown Honolulu, combined with tidally induced flooding, already put the public drinking water supply at risk. If a corroded water main in Mapunapuna should break while submerged in polluted water during a high tide, hazardous chemicals could contaminate the pipeline and the drinking water it carries.

With sea level rise, that type of scenario will be an even greater, if not constant, threat.

The office found that more than 448 contaminated sites would be subject to inundation under a 3.2-foot rise in sea level: 307 sites on O‘ahu, 54 on Maui, 42 on Hawai‘i island, 23 on Moloka‘i, 21 on Kaua‘i, and one on Lana‘i.

“When 1 percent annual-chance coastal flood zone and risk from rising groundwater or additional sea level rise up to six-feet is considered, the count of at-risk chemically contaminated sites rises dramatically,” the memo states.

Before they started mapping which sites would be inundated under various scenarios, Felton says they had a fairly good idea that many of them would be impacted by sea level rise.

They were, however, surprised and concerned at the scope of sites vulnerable to extreme floods on top of a 3.2-foot rise in sea level.

“We know that the intensity and frequency of extreme floods is going to go up,” she says.

The memo offers some examples of the kinds of public and environmental health threats these sites pose as sea level rises and extreme storm events become more frequent:

• Large sections of Honolulu’s shoreline are underlain with fill composed, in part, of lead-laden incinerator ash. This includes Kaka‘ako Park and the land extending several hundred yards inland. Thick caps of clean soil and pavement cover the contaminated fill, but sea level rise or storm surges “could disrupt the caps and spread contaminated fill material along the shoreline and onto adjacent coral reefs,” it states.

• Hilo’s Wailoa River State Park was the site of a Canec plant that produced arsenic-infused wallboard from bagasse in the first half of the last century. Sediment in the park’s Waikea Pond and the soil around it are heavily contaminated with arsenic. Tsunamis in 1946 and 1960 further spread the arsenic into the broader park area.

• The Wai‘anae High School Outdoor Air Rifle Range is located less than one meter above sea level and the soil there is highly contaminated with lead.

• Decades ago, the Ke‘ehi Lagoon Canoe Facility Increment II site in Honolulu Harbor was supposed to become a public park, with areas for race spectators and restored salt ponds for birds. Those plans were dropped after a 1994 site investigation discovered lead and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, which cause cancer, in the soil and groundwater. The department suspects the contamination came from a former asphalt plant in the area, as well as dumping of unclassified fill material into the lagoon to create 10 acres of land. The low-elevation site is directly adjacent to the lagoon and receives stormwater run-off.

The Big Question

So what, exactly can be done to prevent the contamination at these sites from migrating or creating explosive hazards?

“That’s sort of the big question. Are we going to have to figure out a way to remove all of this stuff? That’s the tricky part,” Felton says, adding that determining which sites pose a high risk to human health and the environment is key.

“We’re really in the phase of raising awareness of this issue [that’s] relatively unrecognized,” Felton says.

The memo recommends that studies be done to “examine and measure changing contaminant conditions in high-risk areas and explore mitigation approaches to reduce methane risks and potential build-up of methane vapors.”

It also recommends that criteria be developed to identify high-risk sites, with particular attention paid to “former dump sites and landfills, areas with extensive cover of contaminated fill materials, current and former bulk fuel terminals and related pipeline networks with extensive petroleum contamination and other areas of contamination associated with past industrial activity.”

In addition, it calls for developing guidance, policies, and regulations to address and mitigate adverse impacts and for identifying high risk sites for focused attention and resources to mitigate in a timely manner.

Once the high-risk sites are identified, mitigation options can be considered. “Is it barriers to prevent the sea from coming in? Is it removal of that soil? Is it evacuation of the surrounding area? … There’s not a ton of options,” Felton says.

The removal of contaminated soil, which may have to be shipped to the mainland, is so expensive, it’s a non-starter in a lot of cases, she says, adding that methods to clean soils in place are being developed.

“We’re a long way from having the answer,” she says.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply