Last year, environmentalists and the development community jockeyed over bills aimed at revamping the City & County of Honolulu’s energy code and parking regulations to help mitigate or minimize climate change effects.

In testimony to the City Council, organizations such as Blue Planet Foundation and the Ulupono Initiative lamented that the final versions of these bills lacked features of the originals that would have gone further to encourage the use of renewable energy and electric vehicles, or to get people to eschew traveling by car altogether. They also complained that the parking bill revisions stemmed from closed-door meetings with developers.

Representatives for developers and the construction industry, however, had some complaints of their own. The measures proposed in the energy code bill — even the watered-down version — are expensive and would make it more difficult to keep housing affordable, they argued.

Then-Mayor Kirk Caldwell ultimately signed the bills — Bill 25 and Bill 2 — requiring new homes to be wired to accommodate solar panels and electric vehicles and eliminating off-street parking minimums for new developments, respectively.

No one got everything they wanted, but a valuable lesson was learned: the parties having stakes in these issues should start talking to each other early.

So when Bettina Mehnert, a member of the Honolulu Climate Change Commission and CEO of Architects Hawaiʻi Limited, last month presented a white paper she had drafted on the construction industry’s role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, nearly 90 people tuned in to the commission’s Facebook Live meeting, including representatives from the state’s construction unions.

Mehnert stressed that the paper, which will eventually be adopted by the commission, does not set city policy. It merely informs it. Even so, David Arakawa, executive director of the Land Use Research Foundation, recognized its potential importance: “Policy makers are going to use this document to pass laws,” he said.

Given that, Ryan Kobayashi of the Hawaiʻi Laborer’s Union, Local 368 said the commission needs to engage with a larger scope of people than it usually does. “Sometimes, when things come up in silos, there can be big clashes in the end,” he said.

Nathaniel Kinney, executive director of the Hawaiʻi Construction Alliance — which includes the unions for carpenters, laborers, cement masons, bricklayers, and operating engineers — added, “After going through Bill 25 and Bill 2, what was becoming apparent to the unions was we need to get involved more.”

“The unions are just looking at the overall construction industry. We become kind of the default conscience of what is best for the entire industry, rather than what is best for a single developer or contractor. … We’re the ones, frankly, that are talking to the policy makers more than the contractors or developers,” he said, adding, “We would appreciate being invited to the conversation. Once you get our buy-in, it’s much easier to get the others to buy in. We’re kind of at a critical leverage point.”

At the commission’s December 9 meeting, Mehnert recommended a host of changes to the way the industry operates, from the kind of concrete it should use to the standards to which the state’s architects and new building projects should be held.

The construction industry’s role in climate change is huge, Mehnert said, noting that buildings generate nearly 40 percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions and “the global building stock is expected to double by the year 2060.”

It’s like adding an entire New York City every month for 40 years, she said.

“This growth gives our industry a tremendous opportunity to change the adverse impact on the climate,” she said.

The climate is already getting warmer and the weather is more irregular, requiring more energy for cooling and heating of buildings, so it’s increasingly important to recognize the role of the built environment, she said.

Mehnert recommended that carbon-sequestering concrete, a.k.a. green concrete, be the default product for all buildings and infrastructure. Green concrete is made by taking “waste carbon dioxide from an industrial emitter (usually a gas company or a power plant) and inject[ing] it into a concrete mix, creating a chemical reaction that turns the carbon dioxide into solid calcium carbonate. … The injected mineral replaces some of the cement required for the concrete while maintaining strength requirements. By utilizing the byproduct of a different local manufacturing process, this green concrete decreases the cost of cement, the amount of materials to be transported from the mainland, embeds a polluter into a material, and allows a reduced carbon footprint,” her paper states.

It adds that a 2019 Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation demonstration project, using 150 cubic yards of locally produced green concrete, “will save 1,500 lbs. of carbon dioxide, offsetting the emissions from 1,600 miles of highway driving.”

Although the state doesn’t yet have the capacity to make green concrete the default construction material, “concrete manufacturers will, I am certain, have no objections to fill the demand once it’s there,” she said.

In addition to adopting new standards regarding greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption in new and existing buildings and developments, Mehnert recommended providing developers with incentives to make those projects financially feasible. Eliminating building height limitations was one such incentive.

Doing so would give developers an opportunity to come up with innovative solutions to climate change effects, she argued. She said a developer could increase the height of the ground floor of a building to provide some ability to adapt to increased flooding due to sea level rise.

Increasing the ground floor to allow for some resiliency would force the developer to shave off the top floor to avoid piercing the current building height envelopes. If a developer wants to do the right thing, they should not be penalized by having to eliminate a floor from a building, she said.

One member of the public asked whether building up instead of out would increase air pollution and exacerbate heat island effects.

“Sometimes maybe one has to look at the lesser of two evils,” she replied, posing the question: Is it better to build up in a smaller footprint, and perhaps create a heat island, or does minimizing a heat island footprint justify sprawl?

“I don’t think anything justifies sprawl,” she said, adding that heat island effects could be reduced with green roofs.

Implementing her recommendations will require “a bit of imagination and courage by all of us because business as usual simply will not work,” Mehnert said. “It will require a dialogue that stretches us and that forces us out of our comfort zones. I believe the fact that we have so many people attending this session here is a very good indication that we are ready to have those types of conversations and the intent of this paper is to trigger them,” she said.

She noted that she chose not to specify targets regarding fossil fuel use, greenhouse gas emissions or energy consumption, because stakeholders still need to discuss what those targets should be.

While the rest of the commissioners supported Mehnert’s proposals, they all thought more feedback needed to be gathered, and revisions made accordingly.

“This issue of developer incentives, I think this is a really important point. … There’s this broader question, if you’re pushing infrastructure cost burdens into every individual development project, by definition you’re putting that burden onto the buyer of those units, which has long been a problem. How do we think about this in the context of climate change … when we’re going to ask the industry to be more creative to meet those challenges?” commissioner Makena Coffman said.

With regard to green concrete, Mehnert suggested that transitioning might be one of the easier feats. “This technology has been around for a while,” she said. After reaching out to those in the industry about its use, she added, “what I found incredibly interesting is that it just needed somebody to bring this up. Because the engineers said, ‘Yeah, we can do this.’ And then the contractor said, ‘We can do this.’”

“In the end, we all want to do the right thing. I don’t question this at all. If we put our minds together … we can show the rest of the world how it’s done,” she said.

Climate Action Plan

While the Honolulu Climate Change Commission continues to flesh out and gain broader input for its white paper on the construction industry, the city’s Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resilience has already published several of its own recommendations on energy efficiency in buildings, as part of a draft Climate Action Plan issued late last month and developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi.

The plan is a requirement of a 2018 resolution adopted by the Honolulu City Council, calling for the city to be carbon neutral by 2045.

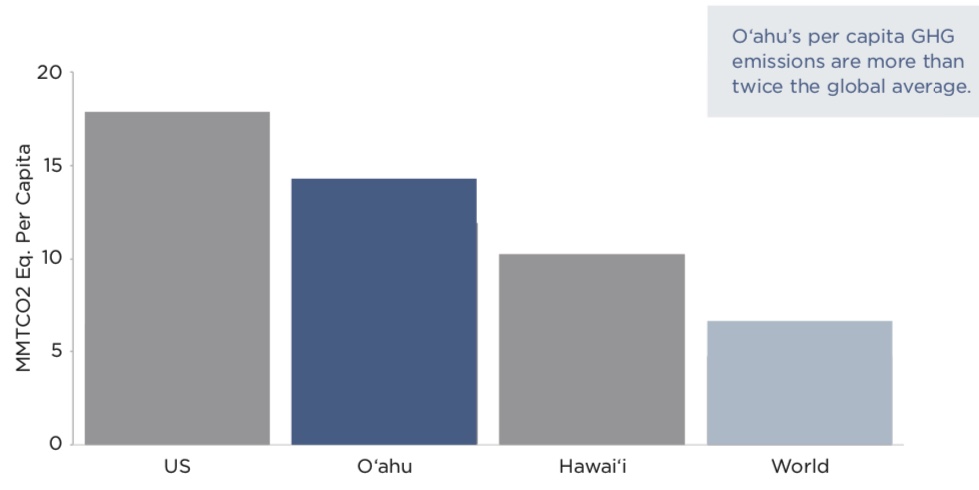

According to the city’s 2020 Annual Sustainability Report, Oʻahu’s building emissions decreased by 21.9 percent since 2005. Even so, as existing buildings account for 35 percent of the island’s greenhouse gas emissions, increased efficiency brings the city a lot closer to its carbon neutrality goal.

The most important long-term way to enable energy efficiency on the island is to “influence new construction by regularly updating building energy codes to the highest national and state standards,” the plan states.

It points out that last year, the city updated its electrical building and energy conservation codes. “However, even in the update of building energy codes, only 2015 standards were adopted rather than the most up-to-date 2018 standards. With the 2021 code on the horizon, the new standards will be quickly outdated,” it states.

The plan recommends adopting a building code ordinance that, at the very least, requires the automatic update of city codes whenever the state adopts new building energy standards. “The city should adopt further standards as appropriate. … Future updates, for example, could address high global-warming potential [greenhouse gases] used within air conditioning systems as there are substitutes,” it states.

With regard to existing buildings, it notes that some U.S. cities have adopted benchmarking and transparency requirements for large commercial and multi-unit residential buildings. Benchmarking, it explains, involves the tracking and public reporting of energy metrics, “which may be particularly useful to inform buyers or renters of commercial space or apartments of their energy costs.”

It notes that commercial and multi-family buildings larger than 30,000 square feet account for 66 percent of the island’s floor space. And by implementing benchmarking standards, it estimates that electricity consumption of buildings could drop nearly by 7 percent by 2030. It also estimates that benchmarking of existing buildings could result in a reduction of 1.7 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent gases between 2020 and 2045. “[There are] potentially large impacts from new buildings over time,” it states.

A third of island residents surveyed by the office supported using public funds to retrofit existing large private buildings, according to the report.

“A growing number of cities including New York, St. Louis, and Washington D.C. have gone beyond by adopting incrementally increasing energy-saving targets for buildings to ensure increasing energy savings over time. The city can begin to replicate these efforts by implementing its own municipal benchmarking program for covered city buildings over 10,000 square feet,” it states.

The plan envisions the development of a benchmarking program, building performance standards, and reporting mechanisms — including the passage of ordinances — to occur in 2022-2023.

“In order to achieve deep decarbonization goals in the existing buildings sector … we need to measure energy usage, evaluate it against peers and other sectors, and then identify opportunities for energy and water conservation,” the plan states, adding that the city will “lead by example and first establish these policies for its own facilities before collaborating with industry partners on a community-wide benchmarking effort.”

In addition to benchmarking, the plan calls for the retrofitting of city buildings, facilities, and operations through 2023 using energy savings performance contracts (ESPCs). An ESPC, the plan explains, is a public-private partnership with an energy service company (ESCO). “The ESPC provides the upfront investment for energy efficiency retrofits and assumes the technical and performance risks associated with the building improvements. An ESCO can help the city find, design, and implement energy conservation and renewable energy opportunities at city facilities that will be paid back through savings in energy bills,” it states.

It notes that the city has already used ESPCs for an islandwide LED retrofit of 53,500 streetlights, the installation of solar photovoltaics at the Kailua Wastewater Treatment Plant, and an energy efficiency program for the Board of Water Supply.

“Initial estimates suggest that the city could achieve up to a 50 percent reduction in electricity consumption for facilities covered by these ESPCs,” the plan states.

Between 2022 and 2025, the plan recommends that the city pursue energy efficiency for city-owned housing. The city owns and operates, or is finalizing acquisition of, 2,508 affordable rental units, the plan stated.

“The aim of these properties is to help meet affordable housing needs. Electricity costs can be a burden on tenants, where a 10 percent savings for the average resident would result in an annual savings of $180 per year. The city should be sure to design these investments in building energy efficiency retrofits such that the energy cost savings accrue directly to tenants,” it states.

“The city should first facilitate investment through partnership with Hawai‘i Energy, but will likely also have to finance some of the up-front costs,” it states. (Hawaiʻi Energy is the service established by the Public Utilities Commission to encourage energy efficiency. It is financed through a charge on electricity bills.)

The office is accepting public comments on the plan through the end of this month. Comments may be submitted to https://resilientoahu.org/climate-action-plan.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply