Last November, Wailuku Water Company (WWC) president Avery Chumbley told the Commission on Water Resource Management that his company doesn’t have enough money to make the kinds of improvements needed to better control the water flowing through the irrigation system he operates.

“We’re at a financial point I’m not sure how much longer I can continue to be able to do this. Had I had more cash reserves, maybe I would have done more system losses work,” he said during final arguments in a contested case hearing over the use of water diverted from Waihe‘e and Wailuku rivers and Waiehu and Waikapu streams, collectively known as Na Wai Eha. (The commission has not yet issued a decision in that case.)

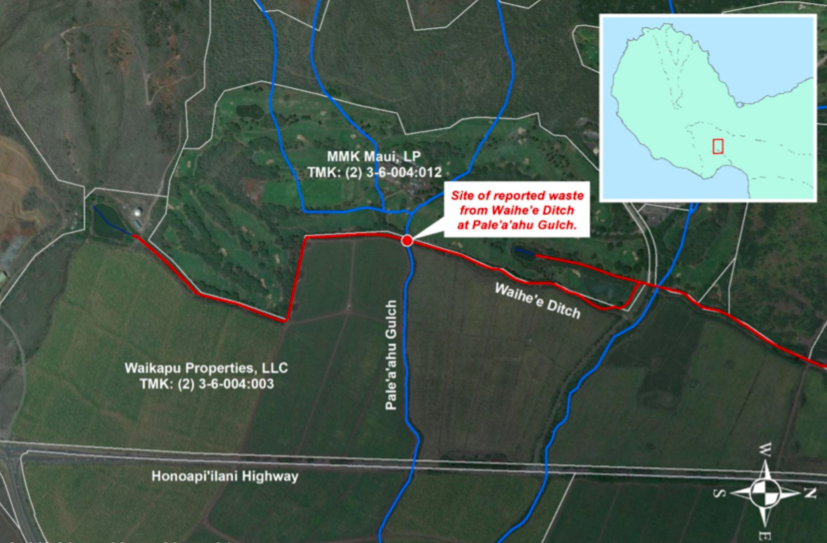

Instead, he said, he has had to release water diverted from those streams that his customers don’t use into Pale‘a‘ahu Gulch, which empties into the Kealia National Wildlife Refuge.

While Chumbley called it a release, commission staff and the community group Hui o Na Wai Eha are calling it waste, which is prohibited under the state Water Code.

At the commission’s February 18 meeting, based on evidence collected by the Hui, staff recommended fining the company $24,500 for 16 days of wasting water in a designated water management area between late September and early January.

Hui members flew to Honolulu to testify on the matter, but Chumbley requested a contested case hearing before they could do so. “There is a lot I would like to say. Wailuku Water Company disagrees with all of the conclusions in the staff submittal,” Chumbley said in making his request.

Once a contested case hearing is requested, the commission is barred from receiving evidence or testimony at a public meeting, unless the commission decides at that same meeting to deny the request. In Chumbley’s case, since his company is the target of an enforcement action, it’s unlikely the commission would find he is not entitled to a contested case hearing.

Citizen Complaint

Before Chumbley made his request, commissioners heard from Dean Uyeno, head of the commission’s stream protection and management branch, on how the agency arrived at its fine recommendation.

After receiving a tip in late September that water was flowing in the normally dry gulch, Hui members began taking note of how often water flowed through it and even dispatched a drone to determine the source.

The group found that water was spilling from an outlet in WWC’s Waihe‘e Ditch that fed directly into the gulch.

In an October citizen complaint to the commission, the Hui wrote that it was disturbed by WWC’s water dumping, “especially during one of the hottest and driest summers on record.”

“In fact, the Na Wai Eha Contested Case that started in 2003-2004 derived from a similar waste complaint in which the Hui filed against WWC who was doing similar illegal dumping of water into Pohakea Gulch, which is the fourth dry gulch in Waikapu just south of Pale‘a‘ahu Gulch. This is truly appalling and a blatant misuse of our public trust resource, let alone the fact that this dumping is occurring during an open contested case hearing, extreme drought conditions and while there are discrepancies aroundIIFSs [interim instream flow standards] in multiple streams across Na Wai Eha,” the complaint stated.

With regard to the flow standard, on September 27, the Hui and Skippy Hau of the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources took flow and temperature measurements of Wailuku River. They found 4.7 million gallons a day (mgd) was flowing and the water temperature was a high 79.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

“This measurement signifies that the 5 mgd at the mouth of the Wailuku River, which is the IIFS, is not being met,” the Hui wrote, adding that the high water temperature does not promote healthy native aquatic species habitat and is detrimental to kalo production.

With the possibility that WWC had been dumping water on and off for “weeks on end, months and possibly on and off for years,” the Hui argued that the only fair remedy would be to issue fines for all of the days the Hui had documented water being released into the gulch.

Commission deputy director Kaleo Manuel forwarded the complaint to WWC and asked the company to formally respond and immediately cease any water dumping.

In its November 15 response, WWC explained that the dumping was due to a number of factors: One of its water customers, MMK Maui, shut down a reservoir for a month to reline it, resulting in reduced water deliveries beginning on September 24. Another large customer, Mahi Pono, reduced its use from 5 mgd to 3 mgd starting around November 1. From October 28 to 31, WWC took additional water in support of the fish ladder instal- lation project on the Wailuku River. The company also stated that its previous efforts to reduce waste — by shutting down some of its reservoirs — also reduced its ability to store, rather than dump, excess water.

To avoid future waste, WWC promised to check in more often with its customers on their actual water needs, instead of relying on their historical use.

Commission staff visited the Pale‘a‘ahu Gulch on November 19. It was dry. But less than two months later, on January 10, Hui president Hokuao Pellegrino informed the commission that water was again being dumped into the gulch, “more than we have ever seen, in fact.” The Hui again submitted photos and video.

Staff concluded in its report to the commission that the Hui’s photo and video evidence suggest that the amount of water WWC released into Pale‘a‘ahu Gulch

considerably negated the company’s efforts over the past decade to reduce system losses “on a single-day basis.” Altogether, WWC claims to have reduced system losses by about 1.3 mgd through repairs, improvements, and the closure of certain reservoirs and diversions.

The report notes that the 16 occurrences of water flowing into the gulch between September 29, 2019 and January 9 of this year did not include the period in October during which the commission had asked WWC to divert water for the fish ladder installation.

Discussion

The commission has the ability to impose fines of up to $5,000 per day per violation. In WWC’s case, staff recommended the minimum daily fine — $250 — for wasting water, as well as an additional $250 per day for committing a violation in a designated Water Management Area. It tacked on another $1,000 a day because multiple violations had occurred after WWC had been told to either minimize waste or stop dumping water. It also recommended a fine of $500 for administrative costs.

While the commission’s penalty policy allows fines to be reduced because of mitigating factors, staff did not recommend any reductions.

At the commission’s meeting, Uyeno said that WWC, to its credit, has taken a number of steps to leave water in the streams. However, he added that the streams are located in a water management area, and the company had been ordered in a contested case hearing to reduce waste. While it may be difficult to prevent waste during high-flow periods, Uyeno pointed out that the waste was occurring in low-flow conditions.

Commissioner Paul Meyer asked what reasonable measures WWC should have taken to allow for greater control over diversions and releases.

“Certainly a monitoring system is needed,” Uyeno replied, adding that old monitoring systems used by WWC and previous system managers are now inoperable. According to the staff’s report to the commission, a damaged intake along the Waihe‘e ditch sometimes results in WWC diverting more water from the Waihe‘e River than needed.

Commissioner Mike Buck asked Uyeno if he had a more specific estimate of how much water had been wasted. “Did you have a number or just some ballpark?” Buck asked.

Uyeno said that just by looking at the photographic evidence, a considerable amount of water flowed through the gulch. “How long it occurred, I can’t say. Perhaps the Hui could provide some information on that,” Uyeno said.

Commissioner Kamana Beamer said he thought 16 separate occurrences was pretty egregious. He and other commissioners asked Uyeno what could be done to prevent WWC’s water dumping.

“It’s always going to be difficult. Number one, better monitoring would certainly help us do that,” he replied, adding that his agency would need daily, if not hourly, reporting. “That can be a burden on different irrigation systems, but is something we need to move forward with. If we had that we could possibly build in system alerts,” he said.

He continued that so many ditch systems run through unpopulated areas or forests that the commission needs people on the ground, like the Hui.

Beamer asked whether having a commission staff person on Maui would help.

Uyeno said it might improve the commission’s response time.

Commissioner Neil Hannahs asked whether people who are allocated water have an obligation to inform the system operator in a timely manner of changes in their water needs.

Uyeno pointed out that the Water Commission had not yet issued any water use permits to any of the parties in the contested case involving WWC’s system. There are contracts between water users and WWC, he added.

Commissioner Meyer asked if WWC would have had more control or flexibility in diverting water if it had fixed the damaged or inoperable control gates on its ditches.

“At minimum, Wailuku Water Company would be able to reduce the overall intake into Waihe‘e ditch,” Uyeno said.

“Did you ask them why they didn’t fix it?” Meyer asked.

“No,” Uyeno replied.

Commission chair Suzanne Case said the commission would later determine whether or not to hold the contested case on Maui.

In a Facebook post the day after the commission’s meeting, the Hui stated that it was prepared to refute all of the reasons WWC gave for its water dumping. “What Avery Chumbley of Wailuku Water Co. doesn’t realize (obviously) as he scrambles to find any and all ways to deny his wrong doing via stall tactics, is that the Na Wai ‘Eha Community has every single stream, diversion, gulch, ditch, and reservoir thoroughly mapped and watched over for any and all missteps on his part. The days of plantation, corporate water theft and their slick legal advisers are slowly fading away and a new generation of kia‘i wai and aloha ‘aina is rising and laying a new foundation for cultural, natural and environmental management and stewardship.”

—Teresa Dawson

For more background, see, “Parties Offer Final Arguments In Na Wai Eha Contested Case,” from our December 2019 issue.

Leave a Reply