Waimea, ‘Anaeho‘omalu Aquifers Remain Separate in Updated Water Resources Plan

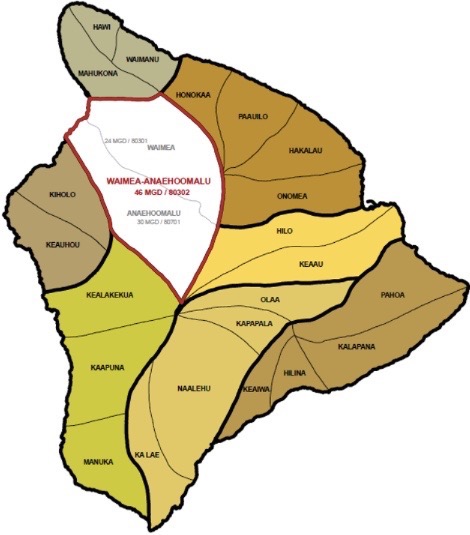

After more than a decade, the Commission on Water Resource Management finally updated its Water Resources Protection Plan (WRPP) earlier this year. As adopted, the plan seems to put the brakes on a proposed 1,200-unit residential development on 1,500 acres in the South Kohala district of West Hawai‘i. The new town, to be called Nakahili, would be built by Maui-based Work Force Developers, LLC, and draw its water from the Waimea aquifer.

Before the WRPP update, that aquifer had a sustainable yield (SY) of 24 million gallons a day. The update, however, reduced the SY to 16, based on recharge estimates from a 2011 report by the U.S. Geological Survey.

As Environment Hawai‘i reported in February, 13.83 mgd, or approximately 86.4 percent of the sustainable yield, is already being used. With a SY of 16 mgd for the Waimea aquifer, “the full build-out of Nakahili may not be realized and alternative plans may be pursued,” the draft environmental assessment for the project states.

At a meeting held in Waimea in June, members of the Water Commission were briefed by staff on isotopic evidence that suggests that the Waimea and adjacent ‘Anaeho‘omalu aquifers are connected. Groundwater program manager Roy Hardy told the commission that his agency and “a group of professionals” — including hydrologists and representatives from the state Department of Health, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Hawai‘i’s Water Resource Research Center, and consultants who work in the area, among others — are proposing to combine the two aquifers into one. “It appears more consistent with hydrogeologic data and it’s a simple management change to address a perceived threat to the Waimea area,” he said, according to minutes of the meeting.

Merging the aquifers would result in a sustainable yield of 46 mgd.

Commissioner Neil Hannahs asked Hardy whether merging the aquifers might mask the need to temper growth or optimize recharge.

“It might,” Hardy replied, but added that was more of a concern for Hawai‘i County’s Leeward Planning Commission.

Commissioner Kamana Beamer noted that only a single isotope study was being offered as justification for the merger and also expressed concern about “treating water like a bank account, and I’m just going to borrow from our neighbor next door, ‘Anaeho‘omalu, without thinking of these larger issues like [groundwater management area] designation, planning, and prioritizing.”

Hardy explained that those were “end of the pipe” issues, which are separate from characterizing the aquifer. He added that water levels in the Waimea aquifer have been steady, suggesting that it is not at risk of overuse.

Beamer suggested that Hardy get input from people who have lived in the area on how the climate has changed. “My great-grandparents were seeing the misty rain come into Waimea almost daily around this time; it has changed where we have periods of drought and some intense periods,” he said.

Hardy said he thought the commission’s low recharge estimates for Waimea reflect some of those changes.

CWRM chair Suzanne Case suggested that rather than merging the aquifers, Hardy might consider just adding a little cushion to the Waimea SY number and monitoring it. “[I]t seems like if you’re close to over-pumping in one area, you don’t want to pump more because it might not be a sustainable number,” she said.

Hardy acknowledged that was a concern, but cited data provided in 2015 by hydrologist Tom Nance that indicates the proposed 16 mgd sustainable yield for Waimea did not take into account about 10 mgd of possible recharge from the Kohala mountains.

Case then asked whether the merger proposal originated with CWRM staff or was a request from the county or developers.

Hardy replied that others had proposed to modify the aquifer boundaries, “but the justification for that is … it’s an opinion. CWRM has combined aquifers in the past.” In 1993, to address similar concerns, the ‘Ewa and Kunia aquifer boundaries on O‘ahu were combined, as were the Waipahu and Waiawa aquifer boundaries, a commission report states.

At its July meeting, the Water Commission was asked to approve the WRPP update, which maintained the 16 mgd SY for Waimea and a 30 mgd SY for ‘Anaeho‘omalu.

However, a two-sentence footnote in the plan indicates that commission staff is “considering amending the boundaries of the Mahukona, Waimea, and ‘Anaeho‘omalu Aquifer System Areas based on observed behavior of existing wells within those areas. Changes in boundary conditions amongst these areas will affect and change recharge analysis and quantities; therefore, the SY estimates in this version of the plan are preliminary until further confirmation.”

While the staff submittal to the commission did not ask for an immediate decision on the boundary merger, it included as background information comment letters on the draft plan from hydrologists and the Hawai‘i County Department of Water Supply (DWS) that supported the boundary merger.

In a March letter, the DWS asked the commission to refrain from reducing the Waimea aquifer’s sustainable yield to 16 until the aquifer boundary changes are ready to be adopted. “DWS believes that adopting new SY numbers without incorporating potential boundary changes at the same time could result in an unnecessarily misleading outlook on resource capacity and that it would be better to include all the pertinent information available to provide the most accurate determinations for sustainable yield,” wrote the department’s manager and chief engineer Keith Okamoto.

Don Thomas of the Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology stated in a May 12 comment on the plan that results of a drilling project in the Humu‘ula Saddle of the island, between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, have led him to believe that the boundary line between the Waimea and ‘Anaeho‘omalu aquifers doesn’t serve its intended purpose. “I … am strongly of the opinion that water flow across currently designated aquifer boundaries is far more common than has been generally recognized: this would include the Kohala/Waimea aquifer boundary as well as the ‘Anaeho‘omalu/Hualalai boundary and many others where aquifer boundaries reflect the intersection of volcanic deposits of younger volcanoes covering their older sister volcanoes,” he wrote.

At the July meeting, Beamer said he thought it would be premature to vote on any aquifer boundary changes given the short briefing at the commission’s previous meeting. Commission staffer Lenore Ohye assured him that any changes to the sustainable yields for either aquifer would be done in a separate action.

The commission unanimously approved the plan, with a few amendments not related to the proposed aquifer merger. A hearing on that proposal, however, was scheduled for October 3 in Waimea. Commission staff set a deadline for public comments of November 3, and planned to bring the matter to the commission for decision making on December 17.

Sparse Reporting

Water Commission staff can tell a lot about the health of aquifers from deep monitoring wells, which allow for the tracking of water and chloride levels. But knowing how much water is actually being pumped from an aquifer helps managers understand what’s going on underground, as well. What’s more, “when actual ground water withdrawals or authorized planned uses may cause the maximum rate of withdrawal to exceed 90 percent of the aquifer’s sustainable yield, CWRM may designate the area as a water management area and regulate water use through the issuance of water use permits,” the WRPP states.

The commission, however, has never had a good grasp of how much water is actually being pumped from wells throughout the state, even though well owners and operators are required to provide pumping data to the Water Commission.

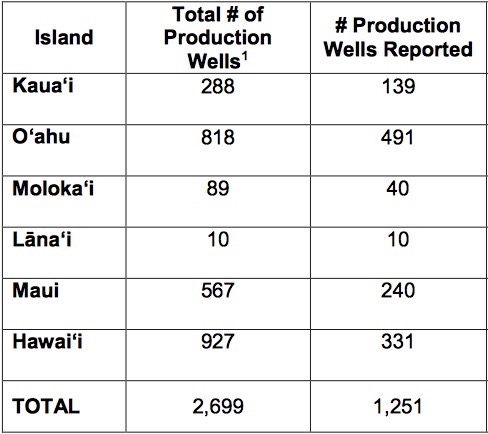

A chart in the plan shows that groundwater use is well below the sustainable yields of each major island, but that conclusion is based mainly on reported pumpage. And according to the plan, only 46.4 percent of well owners or operators comply with the requirement to report their monthly water use. Of the 2,699 production wells statewide, the commission has water use reports for only 1,251 of them.

Still, county water departments are able to provide considerable information on groundwater use. Data on surface water, however, is lacking, the plan states.

Owners and/or operators of stream diversions are also required to report their monthly water use, but often don’t. The only surface water use data in the plan is a 12-month moving average for 2016 for each island, and it clearly does not reflect what’s actually being diverted from streams. Reported surface water use for Moloka‘i, for example, was zero. But according to a petition filed with the commission in July by Earthjustice, on behalf of Moloka‘i No Ka Heke, Moloka‘i Ranch diverts about a half-million gallons of water a day from four streams on the island.

The petition estimates the ranch could have accrued more than $23 million in fines for failing for more than a decade to report its water use.

The WRPP suggests a number of ways the commission can improve reporting, including the use of the Civil Resource Violation System established for the Department of Land and Natural Resources, to which the commission is administratively attached.

Wet Water For DHHL

In its deliberations on whether to approve the WRPP update, Jonathan Scheuer, a consultant for the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL), asked the commission to ensure that the plan explain how the department’s water reservations will be developed, since it is “the keystone document” in the Hawai‘i Water Plan.

Under state law, the DHHL is allowed to reserve water in systems under the Water Commission’s jurisdiction to meet the needs of its beneficiaries. To date, the department has reservations totaling nearly 30 million gallons a day across more than two dozen hydrologic units statewide. The vast majority of those reservations were made in September 2018.

But DHHL officials and representatives, including Scheuer, have complained in recent years that they have improperly faced resistance from government agencies when trying to make use of its reservations. Rather than treating the DHHL like any other municipal customer and providing water through county water systems, some county water departments believe the DHHL should develop its own water.

The updated WRPP presented to the commission did state that existing and future needs of DHHL protected through water reservations, as well as those identified in the State Water Projects Plan (SWPP), “must be incorporated and recognized in the components of the Hawai‘i Water Plan. Additional reservations for DHHL are planned based on the 2017 SWPP future demands.” And the Water Use and Development Plans (WUDP) prepared by each county are also components of the Hawai‘i Water Plan.

Even so, Scheuer wanted the plans to include more direction from the commission. The county water plans need to agree with the WRPP, and “it’s not enough for Water Use and Development Plans to say DHHL has this reservation,” he said, arguing that the plan must also explain how those reservations will be developed.

He said he understood that the commission was treating the WRPP as a living document that could be amended at any time. However, he added, “we don’t have a sense of what the triggers are,” which is worrisome since it took ten years to update the plan.

Commission deputy director Lenore Ohye suggested that it might be more appropriate to include the kind of language Scheuer was asking for in the commission’s framework for updating the Hawai‘i Water Plan, rather than in the WRPP.

However it’s done, Scheuer told the commission, “Counties are subdivisions of state. Just as every other state agency is obligated to help fulfill the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, counties are as well.”

“Getting from paper water to wet water is part of the public trust. It’s about us setting policies to enable that,” commissioner Kamana Beamer added.

“That’s a big statement. Certainly bigger than this meeting,” commission chair Suzanne Case said. Some commissioners also expressed skepticism about the duties being ascribed to them. Still, Case said the Department of Land and Natural Resources, which she also heads, is trying to do what it can to facilitate delivery of water to the DHHL. “I do support that. … How it fits into the legal framework is a bigger discussion,” she said. —Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply