It wasn’t long ago that transitioning to hybrid gas-electric vehicles was seen as a better way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on O‘ahu than going purely electric.

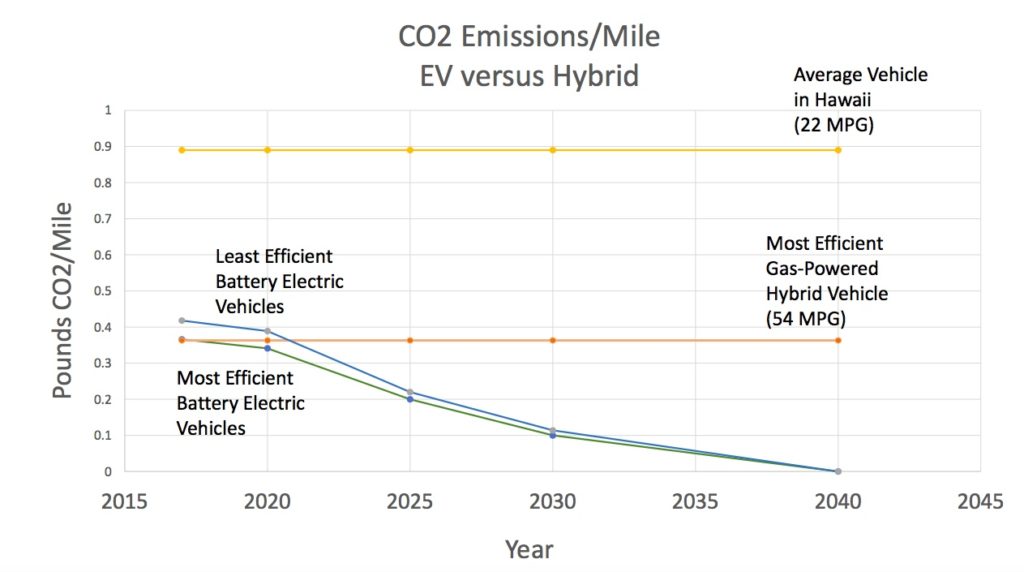

Unlike the neighbor islands that generate more of their electricity from renewable sources, O‘ahu is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels, including coal, for its electricity. “Until O’ahu substantially transitions towards greater penetration of renewable sources for electricity, it may be too early to tout EVs [electrical vehicles] on O‘ahu as a GHG emissions reduction strategy. … O‘ahu’s electricity generation mix must become similar in carbon intensity to that of Kaua‘i and Maui to make high performing EVs at least comparable to high performing HEVs [hybrid electric vehicles] in GHG emissions,” states an executive summary of the University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization’s 2016 Electric Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Assessment for Hawai‘i. UHERO prepared the assessment for the Hawai‘i Natural Energy Institute (HNEI).

How quickly things have changed.

In a presentation last month to the state Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission, HNEI’s Electrification of Transportation project leader Katherine McKenzie reported that as of 2018, an EV on O‘ahu already had a miles per gallon equivalent (MPGe) of about 50, which is roughly that of a hybrid such as a Toyota Prius. She projected that the MPGe for O‘ahu EVs would only increase, albeit slightly, in the next couple of years.

McKenzie’s findings mirror those presented at the same meeting by Blue Planet Foundation’s clean transportation director Lauren Reichelt. Both presentations provided the backdrop to the commission’s discussion of how and to what extent the state should transition its fleet of thousands of vehicles from gas to electric.

Despite their findings, however, some state officials were clearly wary about making any significant changes to their fleets and expressed concerns over the reliability of EVs and inadequate charging infrastructure.

Hierarchy

In 1997, the state Legislature established a state policy to encourage the use of EVs. And a decade ago, it passed a law requiring all state and county agencies, when purchasing new light-duty vehicles, to “seek vehicles with reduced dependence on petroleum-based fuels that meet the needs of the agency.” It also established a hierarchy of those types of vehicles, with the most-preferred being electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles.

Since then, however, state and county fleets remain largely gas-powered. The state alone has 1,333 light-duty vehicles, according to an inventory by commission staff.

At the commission’s meeting, Brian Saito, head of the Department of Accounting and General Services’ Automotive Management Division, attributed his reticence to EV adoption to the poor performance of a slew of Nissan Leafs he purchased for his department in 2011. The batteries never delivered the range they were supposed to, dropping from a starting range of 100 miles down to 50, he said. “People refused to drive it, so we started going with Priuses,” he said.

However, he added that 2019 is the first year he believes the mileage delivered by EVs should be good. He’s acquired one new Nissan Leaf so far, but is waiting to see how it performs before ordering more. “I don’t want to do a whole slew of them and it doesn’t work out again,” he said. (It should be noted that as part of its warranty, Nissan would have replaced the poorly performing batteries of those old models, free of charge.)

Saito said managers of fleets for other agencies are probably not even thinking about buying electric vehicles and that it’s important to educate them about what EV’s can do. The lack of charging infrastructure might frighten them, he said.

Department of Health administrator and commission member Bruce Anderson was certainly one of those worried about that. His department has 118 light-duty vehicles, according to the inventory. Anderson said some of his staff are in their cars all day long and make 15 to 20 stops a day, doing a variety of activities. Nurses, for example, drive 150 miles a day, he said. He argued that the driving patterns of DOH workers would push “the limits of what an EV can accomplish.”

“Reliability is huge for a lot of our staff,” he said.

Reichelt suggested that Anderson should have a consultant take an inventory of what’s actually driven by his staff. She pointed out that some of the new EVs have a range of 240 miles on a fully charged battery. “You can drive around the island twice,” she said.

Still, Anderson worried about the lack of charging infrastructure in places such as Puna on Hawai‘i island and the rural island of Moloka‘i.

According to the Hawai‘i State Energy Office, Moloka‘i has no public charging ports, and Hawai‘i island has 43. Even so, there are 35 and 508 registered EVs on those islands, respectively.

Department of Land and Natural Resources director Suzanne Case, who said she owns a 2013 Nissan Leaf, said that the charging infrastructure doesn’t have to be perfect. She pointed out that EVs can be charged using a regular outlet. “You don’t have to have Level 2 or 3 [standard 240-volt and fast-charging EV ports, respectively] in your garage for this to work,” she said.

Reichelt added that people will be uncomfortable driving EVs at first, but once they change, they’ll like it. In her presentation, she noted that by about 2024, the upfront cost of an electric car will equal that of a gas-powered car.

The Department of Transportation’s Highways Division, at least, has embraced the notion of transitioning to EVs and is working with the state Energy Office on a study assessing charging infrastructure needs for its current fleet of more than 60 light-duty vehicles, as well as needs of medium and/or light duty EV trucks that may be purchased in the future.

Charging Infrastructure

While, as Case said, charging infrastructure doesn’t have to be perfect to ensure that government employees driving EVs won’t run out of power while working, commission members acknowledged that more needs to be done to at least maintain the infrastructure that exists.

In 2009, the Legislature passed a law requiring parking facilities with at least 100 spaces to designate one percent of them for EVs by the end of 2011, and also required them to provide an EV charging unit. That percentage would increase, to a maximum of 10 percent, as the number of registered EVs in the state increased.

While the law established penalties for people who parked non-electric vehicles in designated EV parking stalls, it did not set penalties for developers of parking facilities who failed to install chargers as required, nor did it designate an enforcement agency. Since charging units can cost a few thousand to tens of thousands of dollars or more to install, many parking facilities have ignored their obligations.

“On Maui, we’re having collapsing infrastructure,” said one meeting participant, who called for greater accountability among those required to provide chargers to make sure they actually function. She said the various charging stations on the island are operated by a variety of different companies, which sometimes makes them difficult to use. She recommended that there be a statewide vendor “so there isn’t a public perception that charging is difficult.”

For the 9,360 registered EVs in the state, there are 495 public charging ports, fewer than 10 percent of which are fast chargers. To improve the EV charging infrastructure statewide, the Legislature this year passed a law that establishes a rebate program for parties willing to install new chargers or upgrade old ones. The state Public Utilities Commission, which will administer the program itself or through a third-party contractor, will provide $4,500 for the installation of two or more new Level 2 ports, $35,000 for a new fast charging system, $3,000 for the upgrade of two or more Level 2 ports, and $28,000 for the upgrade of a fast charger. Total annual rebates would be capped at $500,000.

The Legislature also passed a bill requiring all agencies to identify and evaluate vehicle fleet energy efficiency programs “that the agency may implement using vehicle fleet performance contracts.”

Even so, state Rep. Nicole Lowen, who chairs the House Energy and Environmental Protection Committee, said that there needs to be more discussion of how to make sure charging stations are working and the infrastructure benefits the electrical grid. Speaking to the commission’s overall discussion on EVs, Case said, “This is all about us groping our way forward. This is what I call participating in the mess. … This discussion of is going on at the governor’s office level.”

In the end, the commission unanimously called for a lead entity to identify and undertake activities that will help state and county agencies to transition their fleets to “clean, renewable fuels,” including coordinating any necessary implementation, serving as a technical resource and reaching out to fleet managers, and regularly updating the commission.

—Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply