The Kaua‘i Island Utility Cooperative (KIUC) is inching closer to securing a long-term lease for stream diversions that feed two hydroelectric plants on the island’s east side. This month, the utility is expected to release a draft environmental assessment (EA) for the lease.

Theoretically, the utility could be in a position to bid on a lease by year’s end, if it manages to get a final EA accepted without being challenged and if the Board of Land and Natural Resources approves a watershed management plan beforehand.

Standing in the way of that outcome are opponents with a long list of gripes.

Some object to the fact that a small part of the diverted water is sold by Grove Farm to the county Department of Water Supply after passing through the company’s Waiahi surface water treatment plant.

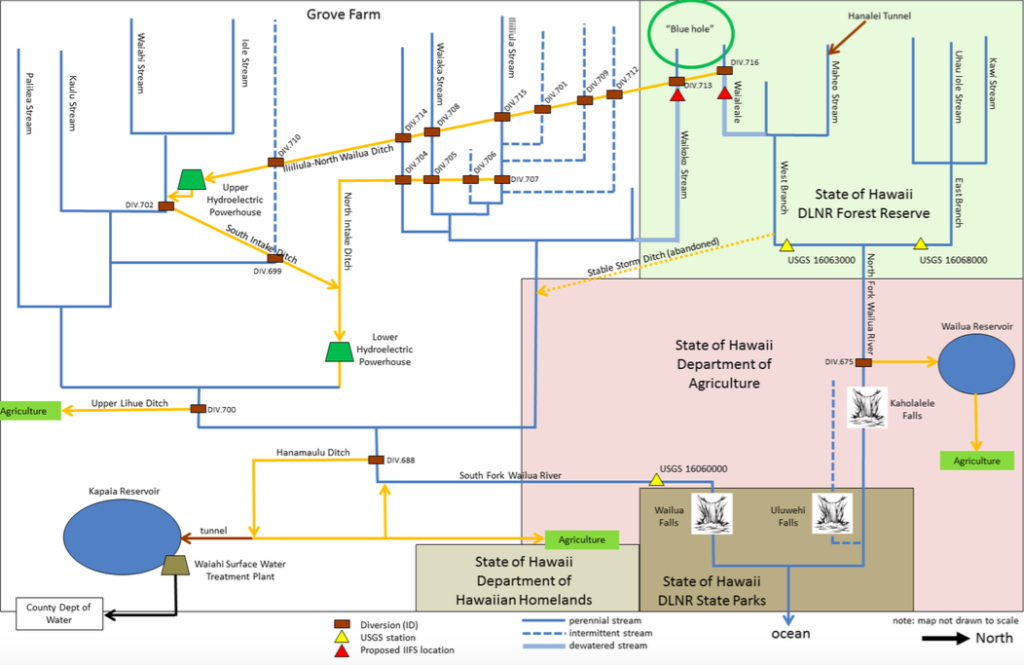

They also argue that the utility’s diversions of Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale streams, which are located on state land, require a full environmental impact statement, not just an EA. Some have demanded that the utility’s permit be revoked, claiming, among other things, that Waikoko Stream has not been restored as required by the existing permit and is dry in one stretch. Others have simply asked the Land Board to impose stricter conditions on the utility’s revocable permit.

At the Land Board’s April 26 meeting, KIUC communications manager Beth Tokioka reported on the outcome of facilitated discussions earlier this year with stakeholders, including those critics, in an effort to address their concerns. In short, mediator Robbie Alm recommended that they enter a formal dispute resolution process that addresses all of the stream diversions that feed the old sugar plantation irrigation system, not just the two on state land.

But KIUC has little time for more talk. The utility’s permit expires in December and it’s unclear whether the board can renew it, since the permit was authorized by a 2016 legislative act that sunsets this year.

Given the discussion at the board’s April meeting, it seems unlikely that KIUC will be bidding on a lease come January 1.

Actual Needs

According to Tokioka, the Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale diversions provide 50 to 65 percent of the water that powers the plants.

Water from about a dozen perennial and intermittent streams on Grove Farm lands join with water diverted from Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale to feed both plants. Tokioka said the utility historically took 14.2 million gallons a day (mgd) from the two streams on state land.

In accordance with its permit approved last December, the utility has been taking a combined 9.6 mgd from the streams, “unless flow is above median flows,” she said.

She said the upper hydro plant needs 25 mgd and the lower one needs 42 mgd for maximum power production of 1.5 megawatts.

Because the Land Board decided last December to limit the amount of water KIUC can take from the streams so that mauka-to-makai flows can be maintained, the plants are likely operating well under full capacity. Given that, Earthjustice attorney Leina‘ala Ley testified in support of a formal resolution process — not necessarily a contested case hearing — to glean more detail about the utility’s need to divert those two streams.

“Where is the water going and what is KIUC doing with it? … There might be further opportunity to consider whether additional permit conditions should be put on KIUC,” she told the board.

In written testimony, she and colleague Isaac Moriwake had proposed several conditions on KIUC’s permit for the diversions. Among other things, they included requiring the installation of water gauges on streams feeding the ditch to help enforce minimumflow requirements, adjusting diversion structures so that they capture high flows, rather than low flows, and requiring KIUC to demonstrate its “actual, reasonable-beneficial need for diversion of water from Wai‘ale‘ale and Waikoko streams in light of alternative water and electricity sources.”

At the board meeting, member Yuen expressed confusion over what the Earthjustice attorneys meant by KIUC’s “actual needs.”

“For full power, they need 25 mgd [for the upper hydro]. Take 1 mgd out, they lose 4-5 percent of their power. What more information do you want to have? I mean, there is a trade-off: power production and the amount of water returned to the streams,” Yuen said.

For one thing, Ley said, alternative water sources needed to be considered. As Kaua‘i resident Bridget Hammerquist testified later, about 26 mgd flows in Waiahi stream alone. Waiahi runs through Grove Farm land and also feeds into the ditch system.

Ley also questioned whether it was necessary for the plants to run at maximum capacity at all times and mentioned the times they’ve been off line. “It’s clear they don’t operate at maximum capacity. It’s not necessary,” she said.

“I suppose nothing is necessary. If the plant broke down, you would probably not have rolling blackouts on the island of Kaua‘i,” Yuen replied. “The issue is, what point is the right tradeoff? People can disagree about that, but I’m just not sure what more information is really necessary,” he continued.

Ley said she wanted to know how often water is taken from the two streams to meet actual power needs.

To Ley’s apparent concern that the streams weren’t being left with adequate flows, Yuen reminded her that KIUC’s revocable permit required 4 mgd to be returned to the streams to provide continuous mauka-to-makai flow. (The KIUC’s Tokioka testified earlier that it has been meeting the permit’s flow requirements.)

“I think there’s a very clear answer as to how much power is generated by having these diversions. Just on an engineering basis, they can give you a very clear answer,” Yuen said. KIUC had testified in December that if the board approved the permit conditions as recommended — which it did — the hydros would produce 22.4 percent less power.

Ley countered that while KIUC has stated its flow requirements for maximum power generation, it wasn’t clear whether the utility is using all of the power generated by the hydros all the time or whether power — and water — is being wasted.

If Ley wanted that kind of detail, Yuen said the utility has figures on the kilowatt-hours generated. “I would think they would run the plant 24-7 if it didn’t break once in a while,” he added.

“I’m really baffled,” he continued. “Earthjustice, if you look at your website, has this, ‘We are in favor of clean energy, we litigate in favor of clean energy.’ I understand, a lot of places people don’t like dams because … [they’re] bad for salmon. I think we pretty much established the last time here the biological benefits of restoring these streams are probably not what we would get in some other places due to the smallmouth bass situation,” Yuen said. According to biologist James Parham, the introduced fish — and not poor stream flow— have suppressed native goby populations in the streams.

“I’m trying to get Earthjustice’s position as an environmental law firm in reducing the amount of renewable energy produced by this plant,” he said.

“I wouldn’t say our interest is in reducing the amount of electricity,” Ley replied. However, she said her firm believes there are missing pieces in KIUC’s justification for taking water from the two streams on state land.

Board member Stanley Roehrig asked Ley’s thoughts on whether the board should simply cancel KIUC’s permit, since concerns had been raised earlier about the diversions’ effect on native Hawaiian traditional and customary practices.

“That’s not what we’ve asked for at this time, but that’s an option the board has,” she replied.

The Water of Kane

Ley’s testimony focused, as did the utility’s draft EA, mainly on KIUC’s use of the water siphoned by stream diversions on state land.

Like Alm, Roehrig took a broader view.

“I have some difficulty understanding how you can be talking about an environmental assessment when you’re diverting a lot of water to Grove Farm, [which is] selling some of that water to the county,” Roehrig told Tokioka.

Tokioka said the EA simply supports KIUC’s lease application for water for its hydros. “We don’t consume any of that water in the plants,” she said.

She explained that KIUC has been conducting environmental studies since 2008 and has been collaborating with Department of Land and Natural Resources staff to make sure the EA will be sufficient. “We’re not doing it in a vacuum,” she said.

To Roehrig’s concern about the sale of water to Grove Farm, Maunakea Trask, a former attorney for Kaua‘i county, argued that there is nothing inherently wrong with diverting stream water for drinking or to generate electricity.

“Everyone’s rights and interests are not mutually exclusive. And neither does any one side — there are no sides — any one party, or individual get to claim the Hawaiian. No one is all business,” he said before pointing out that some of the company’s critics likely drink Waiahi water, since Kaua‘i is such a small island.

“Grove Farm wants to get away from this dichotomy that diversions are automatically non-Hawaiian. There’s nothing inherently pilau (rotten) or hewa (wrong) about water diversions. Hawaiians, out of all of Polynesia, were the best engineers because of ditch diversions. You look at all of Kalalau, that’s all ditch diversions,” he said.

He added that many people tout the fact that ‘Iolani Palace had electricity four years before the White House. “But how did King David Kalakaua light 325 incandescent lights by 1887? How did he light up Honolulu by 1888?” Trask asked.

“Hydros. Nu‘uanu Stream. All that was done by 1888. What is the state cutoff for establishing traditional and customary practices under the Hawai‘i Constitution? Under State v. Zimring, November 25, 1892,” he said.

And Another Thing…

Because opponents of KIUC’s diversions have consistently complained about Grove Farm’s use of the water, company vice president Shawn Shimabukuro felt the need to respond at the Land Board meeting. He first addressed what he said was misinformation that’s been spread about the quality of the drinking water produced by the Waiahi plant.

In both written and oral testimony to the Legislature earlier this year, Hammerquist suggested that the plant’s potable water was somehow toxic because its discharge contained high levels of bauxite, which contains aluminum.

Bauxite occurs naturally in Kaua‘i soils and Shimabukuro assured the Land Board that the Waiahi plant has a state-of-the-art filtration system that eliminates any traces of elements such as aluminum and bacteria. He added that the plant is regulated by the state Department of Health and county Department of Water Supply (DWS).

“Secondly, you’ve always heard Grove Farm is receiving in excess of $2 million a year [for Waiahi water]. This statement is made to portray Grove Farm as being a greedy, big bad corporation. However, just focusing on these revenues that we receive does not provide the compete story. We spent $11 million to build the facility and upgrades,” he said, adding that there is also considerable cost to maintaining the land and reservoirs.

The county water department reimburses Grove Farm about $1.6 million a year for the water, but that covers just the treatment plant’s operating cost and doesn’t include any charge for the electricity needed to run it, he said.

Under an agreement between the DWS and Grove Farm, the company may receive a return on its investment in the plant, but that’s not happened in last 15 years, he continued.

“Really, we’re subsidizing the water. … This is a very critical facility. It provides water to 20 percent of Kaua‘i’s residents. It provides water to the industrial and commercial sectors,” he said.

‘Molecules’

Because of the company’s relationship with KIUC, board member Roehrig wanted Grove Farm to somehow become an official participant in the Land Board’s water allocation process.

Grove Farm was involved in the facilitated discussions held earlier this year, but now that they’ve ended, it’s unclear how the company will continue its involvement, even in the event further discussions are deemed necessary.

“[A]s far as I’m concerned, you’re getting a pass, coming here to say whatever you want, but we can’t look into your operations from this side. It’s all a one-way street,” Roehrig told Trask. “You folks have to come before the Land Board with your petition and we’ll work it out because we get all kinds of testimony against your folks’ conduct. I’m not passing judgment here today on who’s right or wrong. If you want to get it worked out, you can’t just be a visitor,” he added.

Board member Yuen had a completely different take.

“Frankly, I’m baffled by why the Waiahi surface drinking water system keeps coming up in our discussion of the … diversions of Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale streams,” he said. If the water from those streams stayed out of Grove Farm’s ditch system, there would still be plenty of water in Waiahi stream to at least supply the 2 to 3 mgd needed for the water treatment plant.

Trask added that even the state Commission on Water Resource Management doesn’t think Grove Farm uses enough of the water diverted from the two streams to justify its participation in a contested case hearing over proposed interim instream flow standards.

“According to CWRM staff, it is not a direct feed. It was on a molecular level. They acknowledge there were certain water molecules that may have been shared,” Trask said.

“Well, exactly. The molecules of water that get diverted mix with the molecules of water that were there already, and there’s no way to separate,” Yuen said.

Despite Yuen’s and Trask’s exchange, Roehrig stood firm in his belief that Grove Farm needed to get officially involved in KIUC’s water lease process.

Trask countered that the watershed was never designated by the Water Commission as a water management area, which would require all water users to obtain a use permit from the agency.

Even so, Roehrig said a lease from the state to take the water would allow the company to better plan its future.

To this, Trask argued that Grove Farm has constitutionally protected and common law rights as a riparian landowner, “and there is no information to say we are misusing the water.”

“The reason why we’re here today is to share our information. We only get attacked. These are the only venues we have to give the other perspective,” Trask said. He added, “In all due respect, leases from the state are not safe, they are not secure, and they ride the sea of politics just like everything else.”

The diversion’s critics were split.

Ley sided with Trask and Yuen, pointing out that only about 11 mgd is diverted from Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale streams and there is at least 42 mgd flowing through the system before it reaches KIUC’s lower hydro. “If Grove Farm’s interest is 2 mgd, I don’t see how it would tie in to the 11 mgd from these diversions, which is a small, small fraction of what’s flowing through the Waiahi river,” she said.

Hammerquist, however, called it a grave difficulty that downstream users of the diverted water, such as Grove Farm, are “insisting on the maintenance and continuation of those two state land stream diversions, but they’re not on the RP, they’re not someone the Land Board has jurisdiction over. … I don’t believe it’s appropriate for others not on the RP to come in and justify what this RP user gets to take.”

The Path Forward

Trask started his testimony to the board by expressing his dissatisfaction with how the facilitated discussions went earlier this year. While it was the diversion’s critics who had asked for them, when it came time to meet, Hammerquist’s group, Kia‘i Wai o Wai‘ale‘ale, asked that Alm keep discussions with the water diverters and users of diverted water and the other parties separate.

“Then we were in our respective echo chambers. We wanted to get back together. We got stuff to share,” Trask said.

He said the only way to solve the impasse is through the traditional Hawaiian practice of ho‘oponopono. “You come in first with the mind to resolve this. You don’t want to come in wanting to fight more. No sense. You talk … total truth, absolute truth … and then you work though it,” he said.

A contested case is a bad vehicle to resolve this dispute because it takes too long and is way too expensive, he said, adding, “If we can all identify what our interests are, openly and honestly, then maybe we can reverse engineer where we’re going to.”

Consultant Jonathan Scheuer, who paticipated in facilitated meetings on behalf of the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, held the opposite view on how to proceed.

“You have to get this process into a contested case or some other type of proceeding to clarify what people’s rights are, what the rules are, the facts are. … Trying to have a facilitated conversation in the midst of a squishy administrative process doesn’t really help,” he said.

Such a structured process would do better at clarifying the mechanisms through which the DHHL can physically get the water it’s entitled to delivered to its homestead lands, he suggested.

As things are, a bunch of state water gets into the control of a private entity, and, unless it is told to, it doesn’t have to provide water to the DHHL lands, Scheuer complained.

Yuen pointed out that without the diversions of KIUC, waters from Waikoko and Wai‘ale‘ale would remain in the north fork of the Wailua river — and further away from the DHHL’s lands. Scheuer replied that the department was also interested in taking its 30 percent share of any revenue derived from the transmission of state waters.

In any case, he added that the DHHL has not taken a position opposed to the diversion.

Roehrig ended up endorsing a formal dispute resolution process, even though he began by opposing it. Early in the meeting, he said conflict resolution is “a lot slower than you can resolve it by sitting in a room, because when you have a structured format, you have rules of procedure, rules of discovery.”

Once he had revised his view, Roehrig argued that a contested case be held before the Land Board, despite the fact that one that addresses interim instream flow standards is already ongoing before the Water Commission.

“CWRM is good for the instream flows, not for how much are you going to pay for your lease, where does the water go … how much are you going to pay the state for repair and maintenance of waterways,” he said.

When or whether the board — or the stakeholders — will decide how to proceed remains to be seen.

— Teresa Dawson

For Further Reading

• “Board Talk: Water Permits, Detector Dogs,” January 2019;

• “Group Sues Kaua‘i County, Grove Farm Over Water Line Tied to Blue Hole Diversion,” June 2018;

• “Board Talk” (East Kaua‘i Diversion), September 2005;

• “Letters,” April 2005; and

• “Hawaiians, Conservationists Challenge Diversions of Streams in East Kaua‘i,” January 2005.

Leave a Reply