On November 27, 1987, the Signal Puako Corporation filed a petition with the state Land Use Commission, seeking to place into the Urban land use district just over 1,000 acres in South Kohala between the newly minted village of Waikoloa and the four-year-old Mauna Lani resort on the coast.

Twenty-six years and 363 days later, on November 25, 2014, the Hawai`i Supreme Court issued a ruling in litigation over that petition, finding that the Land Use Commission violated state law and failed to follow its own rules when, in 2011, it reverted the land back to the Agricultural District. On the potentially more damaging charges concerning violation of constitutional rights, the state prevailed.

The case has now been thrown back into the lap of Judge Elizabeth Strance of the 3rd Circuit Court, “for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.” At press time, no hearing had yet been scheduled.

A Convoluted History

The history of the redistricting petition is anything but straightforward.

In 1989, the LUC put the land into the Urban District, approving Signal Puako’s plan to provide “a complete support community for employees of the various resorts” along the Kohala coast. Up to 30 percent of the housing units were to be affordable to families earning up to 120 percent of the county median income, while 30 percent were to be affordable to families earning from 120 to 140 percent of the median.

Almost as soon as the LUC approved the redistricting, Signal sold most of its interest to Nansay Hawai`i.

In 1991, a Nansay subsidiary, Puako Hawai`i Properties, sought to amend the conditions, such that now the development would move from being a support community with onsite affordable housing to being more upscale, with affordable housing – 1,000 units or 60 percent of the total housing units constructed, whichever is higher – being provided either offsite or on-site.

Nansay, which had a number of Hawai`i projects, collapsed when the Japanese bubble burst in the mid 1990s. A California real-estate investment firm, Kennedy-Wilson, purchased the mortgage and, in 1998, foreclosed on Nansay. Kennedy-Wilson, in turn, conveyed the land in 1999 to Bridge Puako, a subsidiary of Bridge Capital, an international investment banking firm now based in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

In 2005, Bridge Puako, which by this time had changed its name to Bridge `Aina Le`a, found the affordable housing conditions onerous and petitioned the LUC for relief. That was granted, on condition that 20 percent of the planned residential units, or no fewer than 385, qualify as “affordable” under county guidelines. Bridge had by now identified a development partner, Cole Capital/Westwood Development Group, and it advised the LUC that it would have no trouble completing the affordable housing requirement by 2008. In a gesture of generosity its members probably came to regret, the LUC gave the Bridge five years – until November 17, 2010.

In 2007, Cole Capital/Westwood was no longer involved. Instead, Bridge announced a new partner, DW `Aina Le`a, LLC. According to an environmental impact statement preparation notice issued in the fall of that year, the project now would include up to five golf courses, a lodge, around 2,400 dwellings (including the required affordable housing), 863 agricultural lots (on the surrounding Agricultural acreage), and a variety of commercial uses. Although the plans outlined in this document diverged in several important ways from the conditions set by the LUC, neither Bridge nor DWAL requested LUC approval of the new plans.

Show Cause

Less than a year following the EIS preparation notice, LUC members began to suspect there was little chance that the affordable housing would be completed by November 2010. In September 2008, the commission voted to issue an Order to Show Cause to be served on Bridge, demanding that it explain to the LUC why the petition land should not be reverted to the Agricultural District. The formal OSC was approved on December 9. Longtime observers of the LUC could not recall another time in the near half century of the agency’s existence when it had taken such a measure.

Deliberations on the OSC occurred over the next few months. In June 2009, the commission voted to approve a request from DWAL that it stay any decision and order on the show-cause order. In August, the commission voted to vacate the order, on condition that by March 31, 2010, at least16 of the affordable units would be completed.

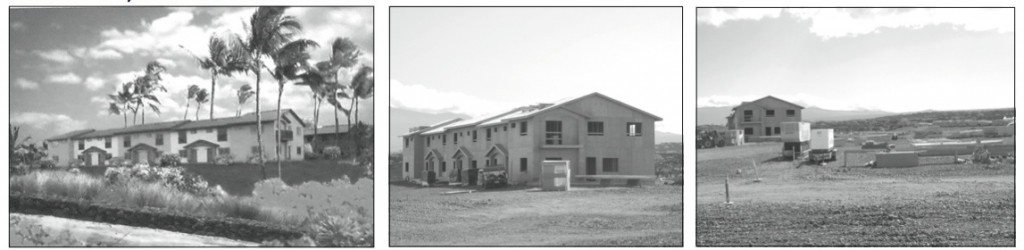

Some six weeks after that deadline passed, the LUC visited the site. They found one eight-unit building – one of 54 planned – mostly complete. One unit had been staged and was being used to market “reservations” to potential buyers. Four more buildings were in various stages of construction.

The model unit had electricity, running water, and functioning toilets – but the sewage flowed into an unpermitted cesspool, the water came from a tank, and the electricity was from generators. Access was over rough gravel roads, and the intersection leading to the property from Queen Ka`ahumanu Highway was still unimproved.

In a progress report provided to the LUC the following month, DW `Aina Le`a said it had “completed” two buildings: “These buildings have completed exteriors and interiors. The electrical and plumbing for the units … is completed and ready to hook up.” The LUC condition, it went on to say, “did not require that DW obtain certificates of occupancy.”

On July 1, 2010, the commission voted to keep the order to show cause pending, with a further hearing scheduled within two months. It also determined that the so-called “condition precedent” for rescission of the order to show cause – the requirement to complete 16 units of affordable housing by March 31 – had not been met.

In late August, DWAL asked the commission to extend the deadline for construction of the affordable housing and amend several other conditions of the project as well. And on November 12, four days before the next scheduled LUC meeting and five days before the absolute deadline for the affordable housing condition had to be met, Bridge asked the LUC to adopt an order that would keep it from acting on the show-cause order at the next scheduled meeting.

As it happened, the LUC did not vote on the order when it next met, but it did at its meeting on January 20, 2011. Then the commission, on a five-to-three vote, reverted the property to the Agricultural District. After three more months of deliberation, on April 25, it adopted the findings of fact, conclusions of law, and decision and order that effected the reversion. The findings laid out in painful detail the litany of broken promises made by Bridge and DWAL representatives since 2005. Among other things, the LUC noted that, “On November 18, 2010, in response to questioning by the commission, co-petitioner DW `Aina Le`a represented that condominium documents had not been submitted, the package wastewater treatment plant had not been delivered and plans not submitted to the state Department of Health for review and approval, no application had been made to the Public Utilities Commission for approval of wastewater or water utilities, no plans for landscaping had been submitted for review and approval by the County, and co-petitioner DW Lea [sic] had not authorized anything to facilitate the construction of the intersection to provide access to the property.”

The Litigation Begins

Almost immediately, both Bridge and DWAL appealed the reversion in Circuit Court. Bridge filed in 1st Circuit and DWAL in 3rd, with both cases consolidated in the 3rd Circuit.

Both Bridge and `Aina Le`a argued that the LUC violated both its governing statutes and its agency rules in that the reversion process did not follow the same procedure as is required of all redistricting petitions; that their constitutional rights to equal protection under the law had been violated; and that their due process rights were violated. Bridge also claimed that the existing county zoning, which permitted the anticipated urban development, amounted to “zoning estoppel” and blocked LUC efforts to revert the land; that the affordable housing condition was unconstitutional; and that the LUC’s action was not supported by the record. DWAL, for its part, similarly argued that the LUC had no statutory authority to enforce the affordable housing condition; that “equitable estoppel” kept the LUC from reverting the property since DW possessed vested property rights; and that the reversion was an unconstitutional taking.

In June 2012, Judge Strance issued a final ruling that basically found in favor of Bridge and `Aina Le`a on all counts. Although the LUC had the authority to redistrict land, she found, counties alone had the responsibility to enforce land use conditions.

Strance also agreed with Bridge and DWAL that the LUC should have followed the rigorous procedures required of all petitioners for boundary amendments and that the reversion vote should have required the same minimum number of affirmative votes – six – as is required for approval of such petitions.

Strance concluded that the long time that the LUC took between the initial order to show cause and the final vote on the order violated LUC rules, which set forth time frames for action. “[I]nstead of following these statues and rules, the LUC implemented a rolling and continuing OSC procedure that not only extended far beyond the 365-day period required [by rule], but also ignored the required procedures, and created new procedures that were not already established,” she wrote.

The due-process and constitutional rights of Bridge and DWAL were violated, Strance found, and the LUC order was “arbitrary and unreasonable, having no substantial relation to the public health, safety, morals, or general welfare.” She agreed with them that their equal protection rights had been violated, with the LUC treating Bridge and DWAL “differently, and less favorably, than other petitioners in cases involving facts and circumstances substantially similar.”

She stopped short of addressing the “zoning estoppel” or vested rights claims by DWAL and Bridge, writing: “The court finds it unnecessary to address this issue because the procedures utilized by the LUC fell short of the necessary procedure and violated various constitutional and statutory provisions. Furthermore, the court has not been able to adequately evaluate those claims based on the evidence and record presented to the court.”

Appeal

The Land Use Commission sought to have the appeal skip the Intermediate Court of Appeals and be heard before the state Supreme Court, a request the justices granted.

The justices agreed with Strance that the LUC did not follow the correct process for reversion in this case, since Bridge and DWAL had “substantially commenced use of the property.” However, they added, “To the extent DW and Bridge argue that the LUC must comply with the general requirements [for redistricting] anytime it seeks to revert property, they are mistaken.”

“The express language of HRS § 205-4(g) and its legislative history establish that the LUC may revert property without following those [redistricting] procedures, provided that the petitioner has not substantially commenced use of the property in accordance with its representations. In such a situation, the original reclassification is simply voided.”

In the `Aina Le`a case, “the circuit court correctly concluded that the LUC erred in reverting the property to agricultural use without complying with the requirements of HRS § 205-4 because, by the time the LUC reverted the property, DW and Bridge had substantially commenced use of the land in accordance with their representations,” the Supreme Court ruled.

The LUC also took a hit for not defining what it meant by having the 16 units “completed” by the March 2010 deadline. The justices noted that in August 2009, DWAL president, Robert Wessels, had informed the LUC that the townhouses would be completed before they would be connected to sewer, water, or electricity. “The LUC failed to state with ‘ascertainable certainty’ that in addition to completing the physical townhouse structures, certificates of occupancy were also required” by the March 31 deadline, the high court wrote. “Thus, to the extent the LUC kept the OSC pending because ‘[S]ixteen affordable units have been constructed, but no certificates of occupancy have been obtained,’ it erred in doing so.”

Finally, the justices agreed with Strance that the LUC erred by not resolving the OSC within 365 days: “The circuit court concluded that the OSC had to be resolved by December 9, 2009, i.e., 365 days after the initial OSC was issued… The LUC’s findings of fact and conclusions of law were not filed until April 25, 2011. Although the LUC had rescinded the OSC on September 28, 2009, that rescission was conditioned upon the completion of sixteen affordable housing units by March 31, 2010. On July 26, 2010, the LUC entered an order finding that the condition precedent was not satisfied, and that the OSC remained pending. Thus, the OSC was not resolved until April 25, 2011, well beyond the 365 days allowed” by statute.

And that is where the concurrence with Strance ends.

Rebuffs

When DWAL and Bridge attorneys were arguing that their clients’ constitutional rights to due process and equal protection were violated, they relied heavily on other LUC dockets that, they said, demonstrated the extent to which the LUC had singled out `Aina Le`a for harsher treatment.

Over the objections of the state’s attorneys, Judge Strance had allowed Bridge and DWAL to put into the record dockets from six other redistricting petitions – a decision the LUC appealed. “Specifically, the LUC argues that the circuit court erred in allowing 9,917 pages of documents from the dockets of six other cases before the LUC to be included in the record. To the extent these specific documents were not before the LUC, the LUC is correct that the circuit court erred in denying its motion to strike,” the high court found.

Although both Bridge and LUC had cited these cases in arguments to the LUC, at no time did they “present documents from those other cases to the LUC to consider…. Also, they did not move to supplement the record on appeal once the case was in the circuit court and did not request that the circuit court take judicial notice of the dockets.”

Strance’s rulings on the question of constitutional rights violations were struck down as well.

The justices noted that customarily they would not make a ruling on a constitutional issue if a question before the court could be resolved by referring to statute. But in this case, they wrote, “Bridge has a suit pending against the LUC and its commissioners in federal court, raising many of the same issues presented in the instant appeal. The federal district court stayed that case pending resolution of this appeal… The LUC filed an appeal and Bridge a cross-appeal from the [federal] district court’s order… The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit heard oral argument on the cross-appeals on June 10, 2014, and thereafter issued an order withdrawing submission of the appeal, pending our decision in this case. In the interest of judicial economy, we therefore also consider the constitutional claims decided by the circuit court.”

The circuit court was within its rights to consider the claims, the Supreme Court found – contrary to the objection made by state attorneys. But it erred when it concluded that there was any violation of constitutional rights.

Strance determined that the LUC had denied Bridge and DWAL their “rights to a meaningful opportunity to be heard” in LUC proceedings. But the Supreme Court determined that “both Bridge and DW had notice and meaningful opportunity to be heard before the LUC reverted the property. With respect to notice, as early as September 2008, Bridge was aware that the LUC was considering issuing an OSC. The LUC issued the written OSC on December 9, 2008. This was two months before DW had obtained any interest in the property. Both Bridge and DW therefore plainly had notice that the LUC might revert the property.”

“With respect to a meaningful opportunity to be heard,” the Supreme Court ruling goes on to say, “Bridge presented testimony … during hearings on January 9, 2009, and April 30, 2009… [A]fter the LUC voted to revert the property, it did not issue a written order effecting the reversion. In fact, the LUC stayed entry of its decision and order and allowed DW to present evidence during a hearing on June 5, 2009. DW also presented additional testimony during a hearing on August 27, 2009. After the March 31, 2010 deadline for the completion of the sixteen units had passed, DW was again heard by the LUC during a hearing on July 1, 2010. The LUC held subsequent hearings on November 18, 2010, January 20, 2011, March 10, 2011, April 8, 2011, April 21, 2011, and May 13, 2011. Bridge and DW were each represented by counsel during all of these subsequent hearings.”

‘Good Reason to be Wary’

In her ruling, Strance stated that the LUC’s final order “was by its terms arbitrary and unreasonable, having no substantial relation to the public health, safety, morals, or general welfare.” Although she was quoting language from an earlier state Supreme Court opinion, the justices found, “the facts of this case do not support such a conclusion.”

At this point, near the end of the 78-page ruling, the justices provide a short recap of the history of the LUC docket, noting that by the time the LUC issued its show-cause order in December 2008, “the land had changed hands numerous times and the LUC had amended the original reclassification order on multiple occasions. Moreover, … by the end of 2008, the landowners had done little to develop the property in accordance with representations made to the LUC. Given this history, the LUC was understandably wary of representations being made by Bridge and DW that they would be able to satisfy the 1991 order’s conditions, as amended in 2005. Nevertheless, Bridge and DW repeatedly assured the LUC that they would be able to complete the affordable housing units by November 2010. As it turned out, however, Bridge and DW did not comply with numerous other representations made to the LUC. Thus, although Bridge and DW may disagree with the process that ultimately resulted in the reversion, the LUC’s conduct was not ‘arbitrary and unreasonable,’ given the long history of unfulfilled promises made in connection with the development of this property. In these circumstances, the circuit court erred in concluding the LUC violated Bridge’s and DW’s substantive due process rights.”

The justices also throw out the claim that the LUC violated DW’s and Bridge’s constitutional right to equal protection under the law. “DW argues that it was treated differently than others who were similarly situated,” they write. “Neither DW nor Bridge, however, have demonstrated that they were treated differently than other similarly situated developers because the documents from the LUC cases involving the other developers were not properly included in the record on appeal.”

Even if they had been able to demonstrate different treatment, the justices go on to say, “their equal protection argument still fails because they did not establish that the LUC was without a rational basis… Given the long history of this property and the LUC’s dealings with the landowners over the course of many years, we cannot say it was irrational for the LUC to exercise its broad discretion by imposing a completion deadline. Again, the LUC had good reason to be wary of any assurances being offered by Bridge and DW, given the history of the project.”

— Patricia Tummons

For Further Reading

Environment Hawai`i has published numerous articles on the `Aina Le`a case over the last few years. Here is an abridged list:

- “Judge Halts Work at `Aina Le`a and Orders Supplemental EIS,” March 2013;

- “A Frustrated LUC Orders Reversion to Agriculture of `Aina Le`a Land,” February 2011;

- “More Promises from Developer as `Aina Le`a Fails to Meet Deadline,” December 2010;

- “`Aina Le`a Seeks Two-Year Extension of Deadline for Affordable Housing,” October 2010;

- “Office of Planning: `Aina Le`a Project Has Not Met, Cannot Meet LUC Deadlines;” June 2010;

- “Under New Management, `Aina Le`a Is Given Yet Another Chance by LUC,” October 2009;

- “After Years of Delay, LUC Revokes Entitlements for Bridge `Aina Le`a,” June 2009;

- “Bridge `Aina Le`a Gets Drubbing from the Land Use Commission,” March 2009;

- “2 Decades and Counting: Golf ‘Villages’ at Puako Are Still a Work in Progress,” March 2008.

All articles are available on our website, www.environment-hawaii.org. Access is free to current subscribers. Others may purchase a two-day access pass.

Volume 25, Number 7 January 2015