“We’re not happy,” Lisa Spain told the room after casting the deciding vote to approve an amended Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) that would allow the state’s largest wind farm to kill 160 more endangered bats than the 60 it was originally allowed to.

The 4-1-1 vote, held at the state Endangered Species Recovery Committee’s meeting on July 25, was a necessary step in finalizing an amended plan and incidental take license/permit for Kawailoa Wind, LLC, which owns a 69-megawatt wind farm on O‘ahu’s North Shore. The facility, which started generating power in November 2012, has been operating in breach of its license for more than a year, having directly or indirectly killed as many as 69 bats as of December 2017. As of March 31, there was a high likelihood (80 percent) that the facility had killed as many as 87 bats, according to a report by the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW).

(Had four favorable votes not been obtained for the amended HCP, the plan would not have received the support of a majority of the seven-person Endangered Species Recovery Committee and would not have been recommended for eventual approval by the state Board of Land and Natural Resources. In that event, under Section 95D-121 of Hawai‘i Revised Statutes, the plan would not be subject to Land Board approval and would instead have to receive a two-thirds majority vote of both houses of the Legislature.)

In addition to any pressure committee members might have felt to support a project that helps the state meet its goal of producing 100 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2045, they also had to face another hard fact: In December 2016, while it did not take an official vote, the committee had expressed its general support of a proposal to consider Kawailoa’s financial assistance in the state’s purchase of lands at Helemano as mitigation for the take of an additional 55 bats.

With some fanfare, the Department of Land and Natural Resources acquired the 2,900 acres from Dole late last year for about $15 million, with $2.75 million of that coming from Kawailoa Wind.

The sale closed one month after Michelle Bogardus of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and DOFAW administrator Dave Smith sent letters to Kawailoa Wind concurring with the company’s approach toward offsetting the take of 55 bats.

Until the July meeting, the ESRC chairman had been Scott Fretz, DOFAW Maui branch manager. Fretz had been highly critical of a draft plan that Kawailoa had proposed last September and which the company had later revised in response to concerns voiced by him and other committee members.

But in the days leading up to the July meeting, Fretz was removed as chair by DLNR director Suzanne Case. Replacing him was DOFAW administrator Smith.

When it came time to vote, Smith repeatedly pressed members for a motion that none of them seemed eager to make in light of the continued uncertainty over how many bats live on the island and whether mitigation measures will actually produce enough bats to help offset the hundreds that may be killed by current and future wind farms.

Rocky Start

Kawailoa’s September draft HCP proposed allowing the take of an additional 205 bats — not 55 — through 2032, when its take license expires. The plan would have added three new tiers to the facility’s three-tier mitigation strategy. The proposed Tier 4 action would be the Helemano acquisition as mitigation for the take of 55 bats. Tier 5 action, which would be triggered once take reached 75 percent of the total authorized take limit for Tiers 1-4 (86 bats), would be some kind of habitat protection (i.e., easement or acquisition) and/or habitat restoration/land management. The action for Tier 6, which would be triggered if and when 123 bats were killed, would be the same as for Tier 5.

The plan also included a “reversion trigger” that would allow Kawailoa to roll back some of its take minimization measures (i.e. feathering turbine blades, using acoustic deterrents) if annual take stayed below 60 percent of the annual average take allowed for in the plan.

At the committee’s meeting last October, members questioned the extent to which the facility should receive mitigation credit for the Helemano lands. In addition to receiving credit for the take of 55 bats by helping purchase the lands, Kawailoa proposed that any future financial contributions it makes to DOFAW to manage the area be considered mitigation for the take of up to 150 more bats. As alternatives, the plan proposed funding of habitat management in native forest in Waimea or some other area acceptable to DOFAW and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Committee member Michelle Bogardus, representing the FWS, said her agency supported the land purchase as mitigation for the take of 55 bats. However, member Kawika Winter, as well as Mililani Browning of Kamehameha Schools, questioned the approach. They noted that some of the lands purchased were already protected by their Conservation District status and that DOFAW would be the agency managing the lands for bats, not Kawailoa.

Spain expressed concern that treating the Helemano acquisition and management as two separate mitigation measures seemed like double-counting.

Fretz later added in written comments that the assumption that the Helemano acquisition would offset the take of any bats, let alone 55, was uncertain, as was the assumption that the proposed habitat improvements or protections proposed for Tiers 5 and 6 would produce 150 bats.

“The conservation biology and recovery needs of HHB [Hawaiian hoary bats] are poorly known. The factors and threats that limit populations are not known, it is not known whether suitable habitat is a limiting factor, and there are no published studies or data on HHB that have demonstrated that restoration of habitat resulted in an increase in HHB populations,” he wrote.

He also complained that the plan did not require the use of deterrents, even though technologies were available that had “a reasonable likelihood of success in reducing take and yielding essential information needed to improve the effectiveness of available methods.”

Fretz recommended a total take of less than 265 bats and that the proposed reversion trigger be deleted.

In response to the ESRC’s comments, Kawailoa submitted a revised draft plan in June, which reduced the proposed total take from 265 bats to 220, removed the reversion trigger, clarified its adaptive management strategy and added sections on the bat population, cumulative impacts, and monitoring.

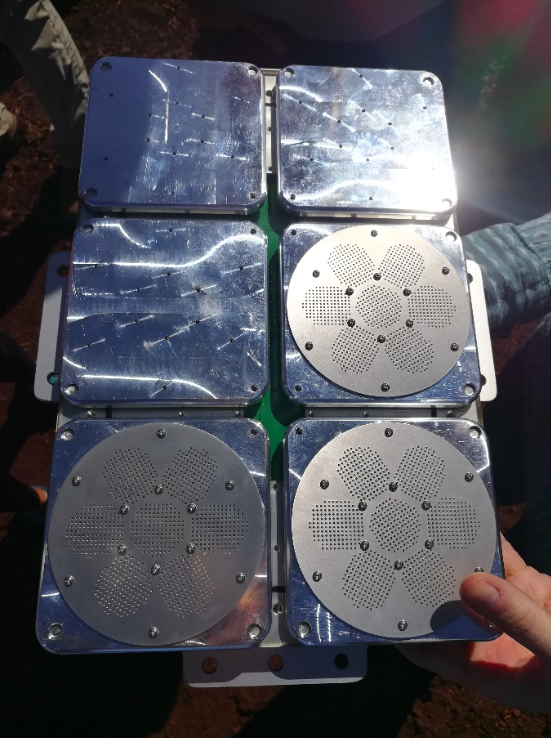

The company also installed acoustic deterrents on each of its 30 turbines.

Brita Woeck, Kawailoa’s environmental compliance manager, informed the committee at its July meeting that the facility is now the first in the nation to install acoustic deterrents commercially. Each turbine has been fitted with several speakers that emit a sound that interferes with the bats’ ability to navigate. The sound extends only as far as the length of each blade, theoretically allowing bats to still forage below and above the hazardous zone.

The installation was completed on June 7. Woeck reported that no bat fatalities had been discovered since then, but could not yet say how the bats were reacting to the deterrents.

“We’re really hopeful this is a trend we’re going to start seeing,” she said.

Kawailoa expects the deterrents to reduce bat fatalities by 25 percent, hence the reduction in the requested take.

“We want to be realistic. We don’t want to come with a fake number. We feel this is the most realistic number,” she said.

The final plan did not identify specific mitigation projects for Tiers 5 and 6, but did propose riparian restoration in parcels managed by the Ko‘olau Mountain Watershed Partnership.

“To mitigate for 85 bats in Tier 5, Kawailoa Wind would target a 1,725-acre area to fund management activities, a 406- acre area would be targeted for Tier 6,” the plan stated. Those numbers are based on using a minimum of 20.3 acres to offset one Hawaiian hoary bat. The 20.3 acres reflects the median core use area of about two dozen bats on Hawai‘i island tagged in a 2015 foraging and range study by U.S. Geological Survey bat expert Frank Bonaccorso.

Woeck acknowledged that Kawailoa needs to start implementing a new mitigation measure soon because it has already reached its trigger for Tier 5.

20 vs. 40

While all of the commission members seemed to acknowledge the fact that no one knows how many acres of enhanced or protected habitat it takes to produce a bat — or even if mitigation should be tied to a particular acreage — some of them expressed concerns over Kawailoa’s use of 20.3 acres/bat rather than the 40 acres/bat recommended in the committee’s 2015 bat guidance document, which was based on the same Bonaccorso data. (The 40 acre number was arrived at by simply rounding down and doubling the 20.3-acre median core use area.)

The guidance document actually points out that Bonaccorso himself “noted that the mean core use area was approximately 65 acres and suggested that agencies should use this value” — rather than the median — “as the acreage for bat mitigation.”

A recent study by a team of researchers with H.T. Harvey & Associates of about a dozen Maui bats suggests that the guidance document is in dire need of revision. The team found that the bats’ core use area — where it spends 50 percent of its time (also known as the 50% kernel) — could be as small as seven acres to as many as 16,000. The average 50% kernel size was nearly 3,000 acres, they found.

At the Hawai‘i Conservation Conference in July, principal investigator Dave Johnston stressed in his presentation on this research that the species should be managed on an island-by-island basis, since the animals are doing different things on different islands.

In light of the Maui study, some committee members were particularly concerned about Kawailoa’s decision to stick with 20.3 acres per bat for mitigation.

“Just like the last time we met, I still disagree with that,” committee member Loyal Mehrhoff said. He said he wasn’t so concerned with that rate being applied to the Tier 4 mitigation, since the Helemano lands would more than accommodate mitigation for 55 bats at 40 acres per bat. He worried about Tiers 5 and 6, however.

Woeck called the 40 acres/bat standard arbitrary and said there was no scientific justification for it. She also explained that habitat restoration benefits will extend beyond the acres managed.

In rebuttal, committee member and USGS biologist Jim Jacobi pointed out that with regard to using the median core use area identified in Bonaccorso’s study, the USGS has “commented several times that is not the appropriate use of that information for calculating that.”

Jacobi then questioned whether a lack of forest cover was actually a limiting factor for bats. “By having more forest, does it give you more bats?” he asked. Bats have been tracked foraging over pasture lands and along gulches and roads.

Woeck said habitat complexity and improving foraging habitat is more important.

The existing information on core use area is challenging given the wide variation among individual bats, Bogardus said. “It’s not an easy data set to make big broad assumptions about habitat. My read is acreage is not the thing we should necessarily use to determine the adequacy of mitigation. … I don’t have a quick and easy metric of what that looks like, which is challenging for all of us. I can’t say 40 acres equals a bat or 20 acres equals a bat … or 100,” she said.

Her agency, at least, has determined that 20 acres is the baseline. From there, facilities have to justify how the mitigation package as a whole will be successful, she said.

Later in the meeting, Mehrhoff made a final pitch against the 20.3-acre standard.

“One of the leading bat biologists says you should be looking at 60 acres-plus. I don’t see anything that leads me to cut that expert’s opinion down to 20 acres,” he said.

Net Benefit

In addition to disagreeing with the method being used to determine suitable mitigation areas, Mehrhoff, at least, thought Kawailoa’s estimate that there were at least 2,000 bats on O‘ahu — and could, therefore, support the cumulative level of take by wind farms on the island — was way off base.

Kawailoa’s HCP suggests that even if all of the wind farms on O‘ahu killed a total of 15 bats/year, that would impact less than one percent of the population. Using two separate approaches, the plan estimates that O‘ahu may support between 2,000 and 9,200 bats and that the population is stable to slightly increasing.

Method 1: The plan assumed that 30 percent of the island — 115,000 acres — is occupied by bats. Based on Bonaccorso’s core use area data from Hawai‘i island, the plan estimated bat density. “O‘ahu could conservatively support 2,000 (115,000 acres/58 acres) to 7,200 (115,000 acres/16 acres) individuals,” the plan states.

Method 2: Studies show that bats occupy more than 50 percent of the is- land. Excluding developed lands to be conservative, Kawailoa determined that bats occupied 147,500 acres (half of all undeveloped lands). Applying the same range of densities, the company came up with a minimum population ranging from 2,500 bats (147,500 acres/58 acres) to 9,200 bats (147,500 acres/16 acres) on O‘ahu, the plan states.

The plan also states that bats have a high reproductive capacity (twinning is common), that more than 90 percent of females are expected to breed in any given year, and that they have high juvenile survivorship.

Even so, Mehrhoff said at the July meeting, “I don’t think there’s 2,000 bats on the island, personally, when I look at the data. … I don’t think you’ve got much more than 1,000.” Mehrhoff is a former field supervisor of the FWS’s Pacific Islands Office.

Noting that acoustic data shows there has been no decline in bat activity, Woeck said there is no indication the island’s population is declining.

To which Jacobi pointed out that bat detectors are now more sensitive than they used to be, hinting that the level of bat activity may actually have decreased even as detections remain steady. He also asked what Kawailoa’s estimate was of the probability that the population is not declining.

Woeck said a study will determine that.

Given that there’s no evidence the population is stable or declining, to say definitively that it’s not declining is “a very strong statement,” Jacobi said.

“This is our best attempt to respond to your request,” Woeck said.

In any case, mitigation is intended to increase carrying capacity on the island, she said.

Under state law, HCPs must be designed to result in “an overall net gain in the recovery of Hawai’i’s threatened and endangered species.” Committee member Winter complained that there are so many unknowns in the proposed Tier 5 mitigation that it was impossible to determine whether it would provide a cumulative net benefit.

To this, Woeck replied that the law does not require Kawailoa to produce a specific number of bats, but merely requires the plan to result in a net environmental benefit. “The fact that we’re a renewable energy project needs to be taken into account. … It’s not about creating one bat. We don’t know how to do that,” she said.

Deputy attorney general Linda Chow clarified that the law requires HCPs to provide a net environmental benefit, as well as an overall net gain of threatened and endangered species.

“To put it simply, endangered species should be better off with this in place,” Winter said, adding that the committee should have some confidence that the plan actually does that before approving it.

Smith countered that the committee also needed to consider “intangibles,” such as the benefits renewable energy brings.

Mehrhoff agreed, but questioned how that is supposed to be done. “This is uncertainty central,” he said.

Regarding net benefits, he said he believed Kawailoa’s estimates of adult mortality were low, and in his analyses, the island’s bat population could not support a take of 220-300 individuals by the various wind farms (total authorized take for the farms on the island would be 307, if the Kawailoa plan is approved). If the population is stable, the population will decline without compensatory measures with that level of take, he said. Even if the population is slightly increasing at a rate of one percent per year, the level of take can only increase if compensatory actions work, and “we have no indication of that,” he said.

Take needs to be down in the realm of 10 bats a year, Mehrhoff said. The average total take of O‘ahu wind farms is anticipated to be 15 per year. “That’s why I’m uncomfortable with Tiers 5 and 6,” he added.

Smith, however, sided with Kawailoa. “We’re actually implementing more deterrents. Our expectation is our take rate is going to go down. … We don’t have evidence the population is declining,” he said.

Mehrhoff replied that there’s a big difference between saying there’s no evidence of decline and saying the project is okay.

An exasperated Woeck asked the committee how they could find some middle ground. “We’re looking at the same information. … How do we get to acknowledging the uncertainty … No one is right and no one is wrong?” she asked.

“That’s what everyone is going to have to decide,” Mehrhoff replied.

Jacobi added that more wind farms have been proposed for the island, which “brings another challenge in terms of how to proceed.”

Anyone?

After even more discussion on bats as well as seabirds (see sidebar), Smith asked the committee if it wanted to entertain a motion.

The committee responded with a long silence. Smith then called for a short break. In the minutes before the committee reconvened, Tetra Tech, Kawailoa’s consultant, and Kawailoa staff conferred on possible changes they could make to help close the deal.

When the meeting resumed, Woeck said Kawailoa was willing to 1) commit to a specific management action for Tier 5, 2) clarify language in the plan’s section on petrels to reflect the opinions of bird experts who believe the birds — perhaps genetically distinct from those on Kaua‘i — are breeding somewhere on the island, and 3) prepare a brief addendum to Tier 5 that specifies success criteria.

After Winter got some clarification on how Kawailoa arrived at its bat population estimate, Smith asked again for a motion and was again met with silence. The committee members sat looking at each other for a while. After several beats, Spain moved to approve the plan with the three amendments Woeck proposed. Bogardus seconded the motion.

Mehrhoff let it be known he wouldn’t be voting in favor. “The take is too high,” he said.

“I’m also uncomfortable with the take level in the higher tiers,” Jacobi added.

While he said he thought Kawailoa’s proposed changes were reasonable, he still didn’t buy the plan’s population estimate. “There are no foundations for those [numbers]. A number of acres gives you a bat? Doesn’t make any sense to me,” he said.

Even so, he voted with Bogardus and Smith in support of the motion, so long as it was understood that there would be a clear effort to involve the committee in adaptive management planning and actions.

Spain did not join them, at first.

“I’m stewing,” she said before finally voting to support her motion.

Mehrhoff voted against the motion; member Winter abstained.

Afterward, Spain explained her reticence. “I think all of us are extremely challenged by the number of bats [to be taken]. … We’re very much hopeful the deterrents will be successful,” she said.

She then urged the committee to update its bat guidance document. “It says 40 acres and we’re being drawn into 20 acres. We need something feasible for us to be pointing back to,” she said.

Bogardus then thanked Kawailoa’s representatives at the meeting for being responsive to the committee’s concerns.

The plan now goes to the Board of Land and Natural Resources, which will ultimately decide to approve it or not.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply