With its proposed Wahiawa Reclaimed Water Irrigation System, the state Agribusiness Development Corporation (ADC) may finally end the City and County of Honolulu’s practice of dumping effluent from the Wahiawa Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) — without a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit — into Lake Wilson and Kaukonahua Stream by diverting the treated wastewater to water-deprived agricultural lands in North-Central O`ahu. If successful, not only will the project finally put to good use high-quality effluent that the city has spent nearly $30 million in plant upgrades to achieve, it may also expand the potential uses of water from Lake Wilson and ensure that thousands of acres of land — which public agencies have committed roughly $100 million to purchase and improve in recent years — have a secure, ample, and unrestricted water source.

“Our whole mission on this is to take R-1 water out of Lake Wilson so we can use it for ag and the lake will become usable water,” said ADC director James Nakatani at a June meeting of the agency’s board of directors.

R-1 is a classification of wastewater that has undergone oxidation, filtration, and disinfection. It is considered the highest quality wastewater and, under the state Department of Health’s (DOH) guidelines for reuse, it can be sprayed on all manner of food crops and even be used as drinking water for livestock (except dairy animals) and poultry.

Although the Wahiawa WWTP currently has the ability to produce R-1 quality water, the DOH has found that the facility does not yet meet the standards for an R-1 facility. “[I]nspections indicate some deficiencies. The one-year certification is acceptable for an R-2 facility,” according to April Mido Matsumura of the DOH’s wastewater branch.

Agricultural use of R-2 water is severely limited. It may only be applied via subsurface drip irrigation to above-ground crops, such as fruit trees, “where the edible portion has minimal contact with the water,” the DOH guidelines state. Because the Wahiawa WWTP’s effluent is still considered R-2 water, water from Lake Wilson, which receives effluent from the facility, is also considered R-2 water.

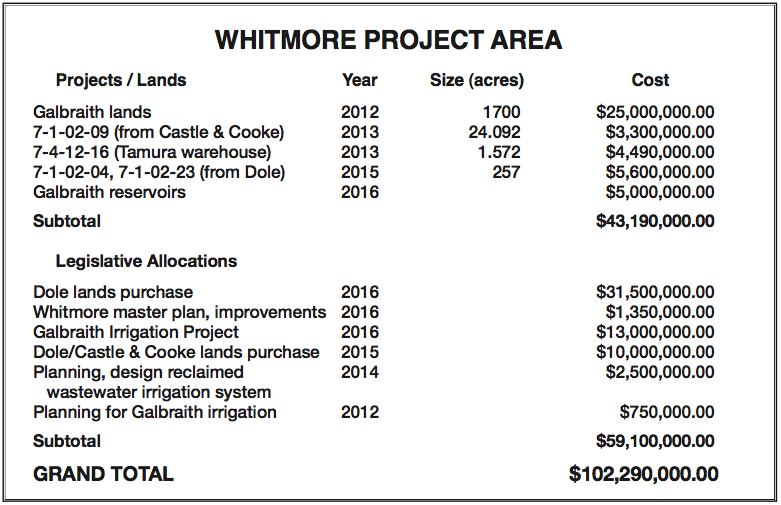

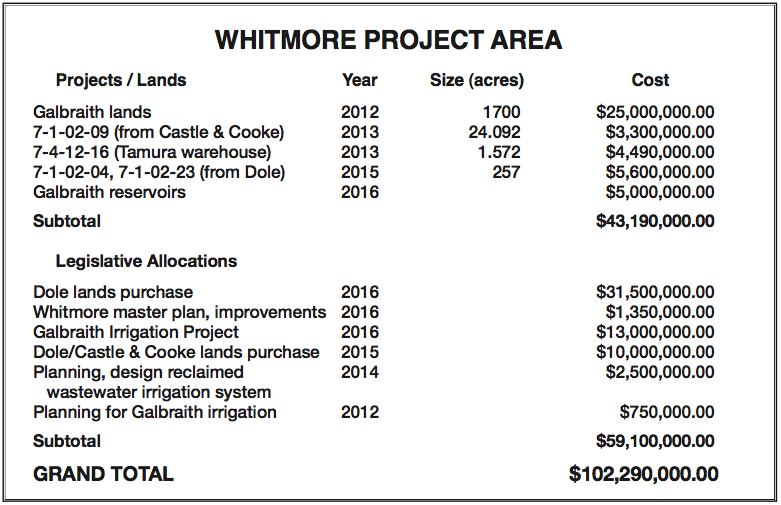

As Environment Hawai`i reported in its July 2015 edition, state Sen. Donovan Dela Cruz’s vision to make the Whitmore area O`ahu’s agricultural hub is quickly solidifying, at least when it comes to acquiring land. Nearly $40 million has already been spent (mostly by the state) acquiring about 2,000 acres there from Dole, Castle & Cooke, and the former Galbraith Estate. In the past two sessions together, the Legislature authorized the issuance of $41.5 million in general obligation bonds to purchase about a thousand more acres owned by Castle & Cooke and Dole.

While some of the lands the state is eyeing have water wells or access to Dole’s irrigation ditch, as of now, the only water source to the fields the state has bought is a single well that can produce at most 2 million gallons of water a day. Nakatani said it isn’t enough to provide water to all of the ADC’s farming tenants all of the time. At most, if crops are rotated and some fields left fallow, the well can serve about 600 acres.

Last year, Kennedy/Jencks Consultants evaluated irrigation scenarios for the area that included various combinations of Lake Wilson water, Wahiawa WWTP effluent, and/or water from Dole’s Wahiawa Irrigation System, which also includes effluent from the wastewater plant. The consultants estimated that bringing an adequate supply of water to the Whitmore lands could cost as much as $11 million, in addition to the $5 million the ADC has already committed to spending on the construction of two reservoirs capable of holding up to 13 million gallons of water.

This past session, the Legislature approved $13 million in general obligation bonds to design and build an irrigation system for the 1,200 acres of former Galbraith lands controlled by the ADC. Picking up where Kennedy/Jencks left off, consultant Brown and Caldwell has been tasked by the ADC to plan, design and build a pipeline to carry reclaimed water from the Wahiawa WWTP to the former Galbraith lands.

As of late August, five potential routes had been mapped out. Some of them passed through Lake Wilson and former Galbraith lands owned by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Another, the least desirable option, ran through Wahiawa town, cut across Kaukonahua Stream, and ended up at one of the reservoirs to be built by the ADC.

“From start to finish, the process will take a couple of years,” said Brown and Caldwell’s Darin Izon.

‘A Straight Answer’

The beauty of the project is that once discharges from the WWTP into Lake Wilson stop, “any water taken from the lake is usable,” said Brown and Caldwell’s Dean Nakano. So in addition to the 1.6-2.5 million gallons of water a day from the WWTP, the ADC may one day have access to many millions more from the lake, which holds more than 9,000 acre feet.

Before any of that can happen, however, the DOH needs to classify the plant’s effluent as R-1 water. In its inspection of the plant last year, the DOH noted that the effluent consistently failed to meet turbidity standards and the plant’s ultraviolet disinfection of the effluent sometimes fell short of R-1 standards. Although the city has improved its disinfection since then and argues that better testing will reveal that the effluent does, indeed, meet R-1 turbidity standards, the issue of storage and backup systems continues to be a major hurdle for the city.

Under Hawai`i Administrative Rules, recycled water systems must have an adequate storage or a backup disposal system to prevent overflows or discharges “when the irrigation system is not in operation or when recycled water quantities exceed the irrigation requirements.”

The Wahiawa WWTP was upgraded to include a storage tank, but that has apparently been insufficient to meet the DOH’s requirements.

In an email to Environment Hawai`i, the DOH’s Matsumura stated, “The county is aware that in order to be considered an R-1 plant, … a back-up disposal system is required. … The county does plan to construct an irrigation system to resolve this.”

What that system will ultimately look like is unclear.

“Hopefully, we can get a straight answer from DOH on the needed storage requirements to get to R-1,” Izon said.

The DOH’s storage requirement is a very difficult thing to meet to get R-1 certification, Nakano added. In addition to a storage system, the agency also requires an emergency backup system to hold water that has not been fully treated. In the past year or so, power outages have forced the city to occasionally discharge untreated or partially treated effluent into Lake Wilson. Under the DOH’s reuse guidelines, the emergency backup storage system must be able to hold at least one average day’s worth of flow, or the average daily design flow of an approved alternate reuse area, whichever is less.

If the DOH’s storage and backup system criteria can be met, it’s likely the DOH will consider this R-1 water, Nakano said.

Jack Pobuk of the city’s Department of Environmental Services would not go into detail about its efforts to meet R-1 requirements, but said the project is under active discussion. It will be at least a year before his agency seeks formal permission from the DOH to use its Wahiawa WWTP effluent for irrigation, given that the ADC must first complete its plans, he said.

As far as efforts to find the best route for the irrigation system, Nakatani said his agency is looking to get an easement across the 500 acres of former Galbraith lands owned by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which also need water. He added that while it might be cheaper today to simply drill wells, the reclaimed water system is a better use of resources in the long run.

Board member Lloyd Haraguchi asked Nakatani whether ADC’s farming tenants would have enough water without the project.

No, Nakatani replied.

Right now, the ADC’s dozen or so farming tenants on the former Galbraith lands occupy some 300 of the agency’s 1,200 acres in the area. License areas range from about six acres to more than 80. At least one small farmer unable to shoulder the rent has recently asked for and received permission to scale back his license area from 20 to ten acres. Although board member Yukio Kitagawa lamented the fact that those ten forfeited acres are now vacant, fellow member Letitia Uyehara commended the farmer’s honesty.

“It remains to be seen how many of these [farmers] can actually ramp up. … Other guys are asking for the moon, 100 acres, and they’re probably going to do 10,” she said.

While some tenants have said they want to expand their areas and there are other applicants for the lands, unless the water issue is dealt with, Nakatani seems hesitant to expand.

“We want to make sure there’s adequate water to farm. The worst thing you could do is put them on the land and there is not adequate water,” Nakatani said.

* * *

Land Purchases

While the ADC and the City and County of Honolulu are toiling away at bringing reclaimed water to the former Galbraith lands, efforts to expand the state’s agricultural holdings in the surrounding areas continue. This past session, the Legislature allocated $31.5 million for the purchase of several parcels owned by Dole, which has put 18,000 acres in North-Central O`ahu up for sale. In April, the ADC board authorized Nakatani to negotiate and purchase two of those parcels, which staffer Ken Nakamura suggested might be good for an orchard or a Christmas tree farm. Only 134 acres in the two parcels are usable; 52 acres are in a gulch.

At the same April meeting, the board gave Nakatani permission to negotiate and purchase about 217 acres owned by Castle & Cooke that are across the street from one of the ADC’s proposed reservoirs. The company is asking $5.35 million. That parcel includes 72 acres of unusable gulch and a 12-acre road easement to the Navy, meaning just over 61 percent of the land can be put to productive use.

In June, the board authorized Nakatani to negotiate the purchase of the fee simple interest in a 91-acre, tree-covered property in Mililani owned by Castle & Cooke.

In 2015, the Legislature appropriated $10 million to the ADC to acquire a handful of properties owned by Castle & Cooke and Dole, including the Mililani parcel. The asking price for that piece is $2.3 million.

Located above Kipapa Gulch, the land could be used to grow pineapple again or an orchard, Nakamura told the board. Although a road leads to the property, it is legally land-locked and the ADC would need to acquire access, he said, adding that while there is access to a nearby water well, there is no electricity.

Still, he said, “we want to preserve the land. It’s one of the most critical components of boosting the economic viability of Hawaii agricultural industry.”

“Of all the inventory that Castle & Cooke has, why this piece?” asked state Department of Agriculture director Scott Enright.

“One, it’s on the market. My thing is, you never turn away what the Legislature gives you,” Nakatani replied. Also, he said, the parcel has potential.

At the ADC’s subsequent meeting in August, the board authorized Nakatani to negotiate the purchase of 895 acres of former pineapple and sugar land in the Whitmore area owned by Dole. Only 761 of the 895 acres are farmable. All of the lands have access to a well and/or Dole’s Wahiawa Irrigation System.

Some of the fields are already being cultivated and require minimal to no preparation, a staff report states. What’s more, the irrigation infrastructure already on the lands could be integrated with the future Galbraith Irrigation System, “thus, increasing the capacity of the entire system which will correlate to increased production on the [former Galbraith lands],” it states.

Dole is asking for $25.7 million for the parcel. Dole’s per-acre asking prices have gone up since the state first started expressing interest in its properties, according to Nakatani.

* * *

‘Import Replacement’

The bill for acquiring land to turn the Whitmore area into a thriving agricultural center is quickly approaching $100 million. And in the past session alone, the Legislature approved tens of millions of dollars more for various irrigation infrastructure and ag technology projects across the state. The target driving much of this largesse is increased food sustainability, which Gov. David Ige underscored with his commitment last month to double local food production by 2030.

The agency tasked in large part with spearheading efforts to turn the state’s agricultural investments into thousands of acres of locally grown food, however, is actually rather skeptical of the idea.

In discussing the crops being grown by its tenants on former Galbraith Estate lands, ADC board member Letitia Uyehara expressed concern that the bulk of them seemed to be planting the same thing — Japanese cucumbers, bananas, tomatoes, okra, asparagus, bitter melon — and wondered about the local market’s ability to absorb all of these crops.

State Department of Agriculture director Scott Enright asked whether the ADC should actively encourage import crop replacement by stipulating in future leases or licenses that the agency is looking for import replacement crops, “so we don’t have Thai basil shipped off to Chicago.”

To say the idea wasn’t well received by the ADC is an understatement. “I see Jimmy twitching,” Enright said, referring to ADC executive director and former DOA director James Nakatani. Still, Enright impressed on the board that legislators and the governor — “people in the square building” — seem to be leaning toward import crop replacement.

As things stand, the ADC’s largest tenants grow crops, seed crops in particular, for export.

“Sixty-six percent of everything we grow in the state is exported,” Enright said. “We’ve always been an exporter, but there is a movement in state government to utilize more land resources for food sustainability.”

Although he said he agreed with the basic idea, ADC board member (and also a former DOA director) Yukio Kitagawa said, “I think we should have individuals who would like to export [and] encourage those that want to grow basil and pineapples …”

Board member Jeff Pearson, director of the state Commission on Water Resource Management, asked Enright whether those government officials seeking greater food sustainability could state a percentage of crops they want kept in the state. “It would take the pressure off us,” he said.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see that,” Enright replied.

Whatever goals government officials set, some ADC board members stressed the need to let the marketplace determine where crops go.

“Farmers are in it to make money,” said Uyehara, marketing director for Armstrong Produce, Ltd. She pointed out that on Hawai`i island, there are thousand of acres of lychee. “They need to export it. They make more money on it. Just sort of let the marketplace dictate what happens. … The state cannot consume everything that is grown. The market is going to fall out and they’ll lose the crop,” she said.

Board member Sandra Kato-Klutke related a similar story about a sheep ranch on Kaua`i that exports its lambs. When she asked them what it would take to keep the lambs on the island, “they say, ‘Sandi, if you can find me someone who will pay what I get from the mainland, I’d be glad to. I need to make money.’”

She also lamented the narrow range of crops at local farmers’ markets. “Kale and okra. Every single booth has kale and okra. I don’t eat kale and don’t eat okra,” she said. To better educate growers about the local market’s needs, she said she planned to have them meet with local chefs who can tell the farmers what they’re looking to buy.

Board member Douglas Schenk noted that often times a grower will lose money on one crop, but on a small part of their product mix, “if they can export, it will carry the whole show.”

“That’s why I was concerned looking at all of these [Galbraith crops], the sameness,” Uyehara said.

Enright wasn’t surprised by the sentiments and said he agreed with what had been said.

“It’s sound logic that doesn’t always prevail,” he said.

“We need to strategize how we utilize these lands so we satisfy their desires as well as the business people growing it,” member Denise Albano said.

The key to any such strategy, Kitagawa suggested, is having willing and able farmers.

“The question I ask myself is, who’s going to grow it? All these here” — referring to the list of new lessees for the Galbraith lands — “is not local guys. [Many are Laotian] … It’s a real issue. Nobody wants to admit that it’s not only talking, you gotta do it.”

— Teresa Dawson

For Further Reading

Environment Hawai`i has published these other articles providing additional background on the subject. All are available on our website, http://www.environment-hawaii.org. Earlier ones may be read free of charge; to read more recent articles, you must be a subscriber or must purchase a two-day archive pass for $10.

- “Bringing Water to Land ADC Acquired Near Whitmore Could Top $11 Million,” July 2015;

- “Water May Be Limiting Factor On Former Galbraith Ag Lands,” December 2013;

- “ADC: Tobacco License, Galbraith’s 1st Lessee, and More,” June 2013;

- “ADC Supports Intent to Buy Whitmore Village Lands,” February 2013;

- “ADC Gives Ho`opili Farmers First Shot at Large Chunk of Former Galbraith Land,” January 2013;

- “Senator Accuses Agribusiness Board of Doing Nothing to Fulfill its Mission,” August 2012;

- “Dam Safety Trumps Effluent Concerns at Central O`ahu’s Wahiawa Reservoir,” August 2009.

Leave a Reply