On March 10, contrary to a request from the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC) for immediate action on its petitions to amend the interim instream flow standards (IIFS) of about two dozen East Maui streams, Commission on Water Resource Management chair Suzanne Case ordered the reopening of the contested case hearing stemming from those petitions.

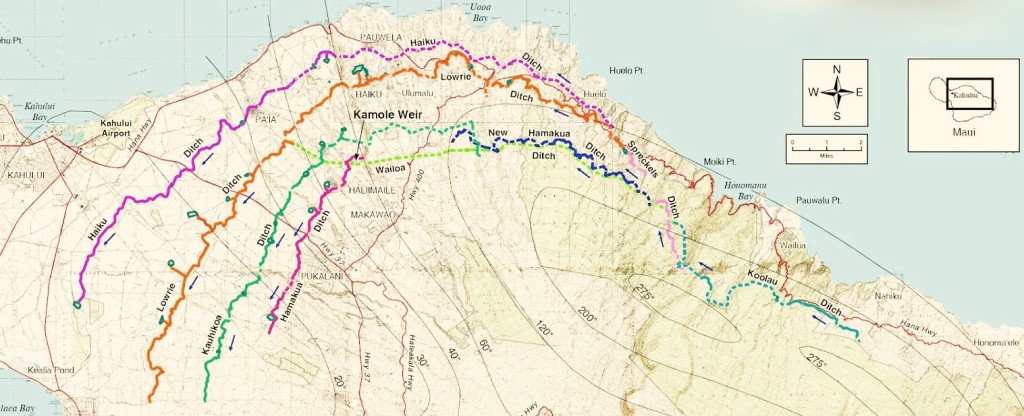

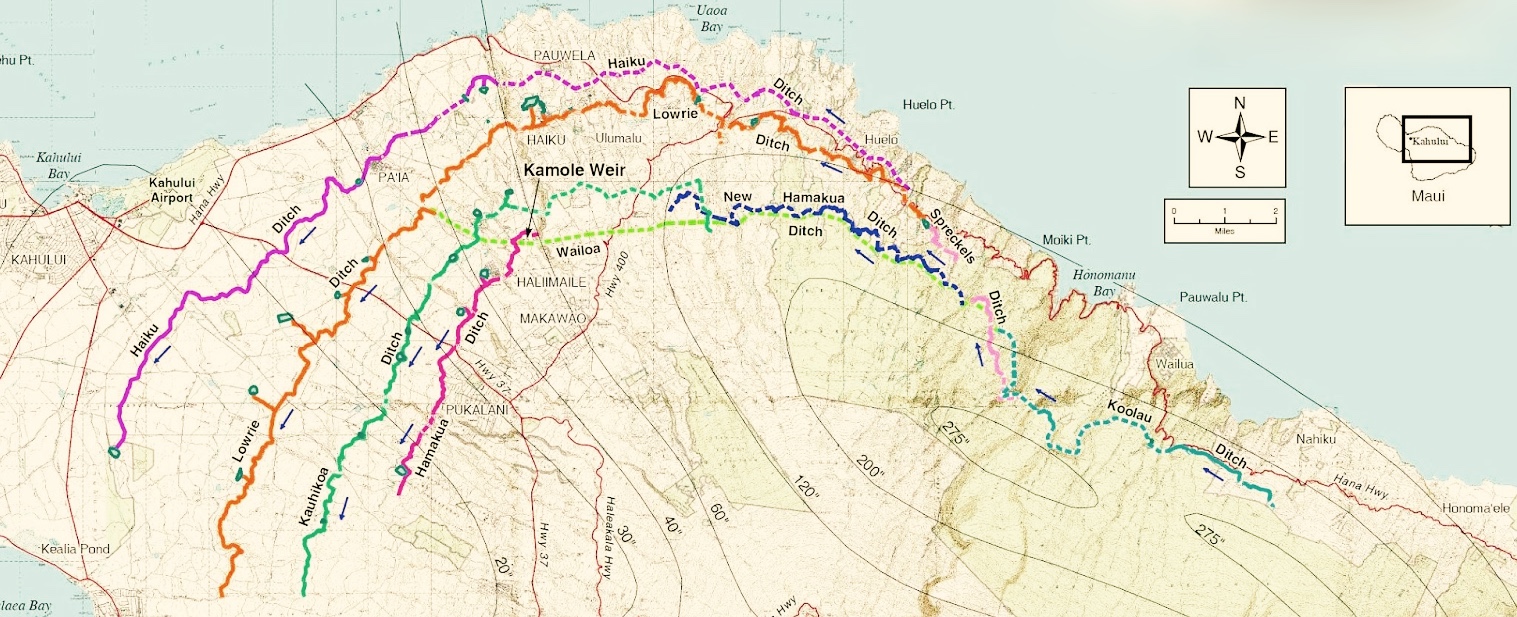

Hearing officer Lawrence Miike had concluded the hearing last April and issued his proposed findings of fact, conclusions of law, and decision and order on January 15. His report came out a little more than a week after Alexander & Baldwin, Inc., announced that its subsidiary, Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar, Co. — the main user of the more 100 million gallons a day (mgd) of stream water diverted from East to Central Maui — would be harvesting its final sugarcane crop this year and that the lands would be used instead for diversified agriculture.

Miike proposed that the Water Commission restore between18 mgd and18.6 mgd to some of the streams to meet the needs of East Maui ecosystems and residents with appurtenant and riparian rights.He found that about 182 mgd of the plantation’s demand – 140 mgd for sugarcane, 6.7 mgd for industrial uses of HC&S, and 35 mgd in irrigation system losses – was reasonable. However, he also found that the draw on East Maui streams could be reduced if A&B supplemented its water demand with 83.3 mgd from its brackish wells. That would result in about 105 mgd from East Maui streams still needed to irrigate the company’s 36,000 acres of cane fields in Central Maui.

Although Miike’s recommendations were based on now-outdated assumptions about HC&S’s water needs, NHLC attorneys Summer Sylva and Camille Kalama requested in their February 29 exceptions that the Water Commission decide the case “expeditiously on the current record.”

They noted that their clients, taro farmers and cultural practitioners from East Maui, filed their petitions more than 15 years ago and that the delay in rendering a decision on them “has harmed aquatic life as well as petitioners’ ability to engage in their traditional and customary practices.” They added that a decision in a parallel case before the Board of Land and Natural Resources on a long-term lease request by A&B to continue the stream diversion has likewise been delayed pending resolution of the IIFS amendments.

“The Commission will have the opportunity to address the changed circumstances at a later date, as will all interested parties. Delaying a decision on the current record to address changed circumstances, however, only prolongs the harm to the resource and the prejudice suffered by petitioners,” they wrote.

Case, however, seemed to want the Water Commission to base its decision on a more current record. As attorney Issac Hall argued in his exceptions to Miike’s report, HC&S, A&B, and its subsidiary, the East Maui Irrigation Company, may not “lawfully reserve, assign or transfer any of the water arising on state lands or any of the allocations of water deemed reasonable and beneficial in this report to other parties whose particular uses and needs have not been fully analyzed in the report.”

Although Case left it up to Miike to decide what additional evidence should be submitted, she stated that it should ultimately lead to a rebalancing of instream versus non-instream uses and a reassessment of the proposed IIFS amendments.

The reopening of the contested case pushes a Water Commission decision on the matter closer to the end of the year, when HC&S will be completing its final harvest, NHLC attorney Kalama said at a March 21 state Senate Committee on Water, Land and Agriculture hearing on a bill (HB2501) relating to the authority under which A&B may continue diverting the streams pending the issuance of a long-term lease.

“We are looking at a several-months-long process at best,” she said of the reopened contested case. No new hearing dates or filing deadlines had been announced by press time.

The longer it takes for the Water Commission to make a final decision on the IIFS, the longer it will take Alexander & Baldwin to complete the environmental impact statement (EIS) necessary for the long-term water lease it requested from the Land Board in 2001. Without an EIS, the Land Board cannot put such a lease up for public auction. NHLC attorneys have suggested at public hearings that its clients might consider bidding on the lease, as well, to ensure the streams are restored.

Balancing Act

With the reopening of the contested case hearing, Miike is now free to base his recommendations on the fact that HC&S will need significantly less water for its final sugarcane crop this year, which, according to statements by A&B, will only cover about 16,000-17,000 acres. Miike has already stated in his recommendations that HC&S’s brackish wells could safely supply enough water to irrigate an area that large.

As of a few weeks ago, the company was unable to give state legislators many details about what diversified crops will be grown after the sugar plantation is closed.

“We don’t have a firm road map,” A&B president and CEO Chris Benjamin told the Senate committee last month. “We envision biofuel crops as a big part, irrigated pastures, food crops, and new crops such as industrial hemp,” he said, estimating that the company’s long-term water needs will be 135-155 mgd.

In its exceptions to Miike’s recommendations, HC&S stated that the only scenario that would require the same amounts of water as sugarcane would be the farming of tropical grasses or cane for biofuel across all 36,000 acres.

Benjamin testified to the committee that HC&S’s brackish water wells may be too salty to serve as an alternative water supply, especially for a crop such as hemp. (At present, the company does use about 70 mgd from those wells, he said.)

“We realize diversified ag will be a challenge. We want to give it the best chance we can,” he said.

With regard to short-term water needs, Benjamin said that HC&S’s final sugar crop will require 95 mgd and that the company will need 45 mgd after its harvest to irrigate cover and trial crops.

How Miike will factor HC&S’s and A&B’s current and future water needs into his revised IIFS recommendations remains to be seen. In their exceptions to his recommendations, attorneys for the Maui Tomorrow Foundation (MTF), Na Moku Aupuni o Ko`olau Hui, Lurlyn Scott, and Sanford Kekahuna argued that he has already taken a backwards approach to setting the IIFS and has given HC&S’s needs far too much weight.

Attorney Hall, representing MTF, pointed out that the Hawai`i Supreme Court, most recently in its 2014 decision on the Kaua`i Springs case, has ruled that a “fundamental principle of the public trust doctrine precludes assertion of prior uses or vested rights to use water to the detriment of public trust purposes.”

“The required starting point is, therefore, 27 undiverted, free-flowing streams,” Hall argued.

Kalama and Sylva of the NHLC further asserted that Miike’s proposed decision “erroneously assumes that previously diverted streams are a foregone conclusion. That assumption informed the hearing officer’s effort to accommodate HC&S’s water needs as an offstream, out-of-watershed user and to term it ‘balancing.’ ”

And Miike’s final recommendations were far from balanced, they claimed. In his report, he proposes restoring up to 18.6 mgd to 23 of the 27 petitioned streams. That amount, Sylva and Kalama stated, would: 1) leave streams with as little as five percent and at most 64 percent of flows necessary to support minimum stream habitat requirements; and 2) satisfy only 43 to 50 percent of their clients’ water needs for taro, despite the fact that they have no alternative water source.

In contrast, they continued, the proposed amended IIFS would make 96 to 149 mgd available to satisfy what Miike found to be HC&S’s 105.6 mgd reasonable and beneficial use of diverted water. Thus, the IIFS would meet 91 to 141 percent of the company’s water need, they wrote. They also noted that HC&S does have an alternative water source, its brackish groundwater wells, that would ensure that 100 percent of company’s water needs are met.

Habitat Needs

In addition to arguing that state law requires that minimum flows must be returned to all streams, the NHLC identifies specific amounts of water — based on the state Division of Aquatic Resource’s (DAR) calculations — that should be restored to Puahokamoa, Haipuaena, Palauhulu, and Waikamoi streams.

DAR staff testified during the contested case hearing that to provide adequate habitat for stream fauna, the streams need a minimum flow equivalent to 64 percent of the natural base flow. (That level is often referred to as the H90 level, which is the minimum flow necessary to support 90 percent of the natural habitat in a given stream.)

Using that standard, the NHLC argues in its exceptions that those four streams need at least 9.5 mgd more than what Miike proposed:

- Puahokamoa: Miike recommended leaving the IIFS at the status quo level of 0.26 mgd, 3.49 mgd less than the H90 level of 4.33 mgd.

- Haipuaena: Miike also recommended leaving the IIFS at the status quo level of 0.06 mgd, less than a third of the 2.13 mgd required to meet H90 level.

- Palauhulu: Miike recommended decreasing the IIFS to 3.56 mgd, which, the NHLC argued, would leave only 1.56 available for the instream habitat after taro irrigation needs were met, “which is far short of the estimated 4.55 mgd required to satisfy the minimum 64 percent median base flow.”

- Waikamoi: Although Miike recommended increasing the IIFS, it was 0.9 mgd below H90 the level.

In MTF’s exceptions, Hall focused not on the water amounts needed to meet instream needs, but on how A&B’s diversion system hampers the ability of stream organisms to traverse the stream course and diminishes the wildlife, fishery, scenic, aesthetic, recreational, and other uses of the streams, many of which are diverted multiple times.

Seven of the 27 streams are each diverted between four and five times, he wrote, adding that such diversions leave segments of streams dry.

“The existence of these dry segments (that only exist because of the diversions) has emboldened some to claim that the streams are not gaining and are, instead, intermittent,” he wrote, noting that Water Commission staff refer to them as “artificially intermittent.”

“Public trust principles require that the causes of this artificial intermittency — the diversions — be modified to restore the streams to their original gaining nature. Accepting their artificially intermittent status caused wholly by ‘prior uses’ constituted by the existing diversions has placed in jeopardy or eliminated uses explicitly mandated for protection as public trust purposes,” he wrote.

“For streams diverted more than once, the upwards and downwards migration of protected species is not possible,” he added. Hall argued that the diversions must be modified to include a “trough style” bypass to allow for migration and that sluice gates, which he said currently do not open wide enough to provide for minimum stream flows, should be enlarged.

Addressing the diversions’ impact on scenic, aesthetic, and recreational uses, Hall wrote that one of the greatest losses resulting from the diversion of Honomanu Stream was the dewatering of the “once magnificent” waterfalls found near the 500-meter elevation. He noted that the Sierra Club has led hikes to the area for nearly 20 years and “it has become increasingly difficult to find any water visible in these waterfalls, since it is all taken by the EMI diversions.”

“These falls, on public land, are now dry except during heavy rain events when access to the area is not safe,” he continued. “This means that the public is denied the opportunity to enjoy the beauty of a public trust resource located on public land.”

Human Needs

The NHLC and Hall both slammed the proposed amended IIFS for failing to adequately meet the needs of East Maui residents who have constitutionally protected rights to stream water.

First, the NHLC argued, Miike improperly borrowed the taro water budget used in a similar case in West Maui, known as the Na Wai Eha case. In that instance, the Water Commission determined taro needs 130,000 to 150,000 gallons per acre per day.

Testimony from expert witness Paul Reppun, an O`ahu-based taro farmer, suggested that a more reasonable amount was 100,000 to 300,000 gallons per acre per day, which represented the maximum amount of water needed to keep taro cool at the most critical part of its growth cycle.

Miike, the NHLC stated, chose instead to base the amended IIFS on “an unworkable average that provides the taro crop with only half the water it needs to survive for an extended period of time. … That calculation is not only ‘backwards’ but clearly erroneous.”

In addition to recommending an increased water budget for taro, the NHLC argued that Miike had improperly failed to include nearly 32 acres of lands in Ke`anae and Wailua that have appurtenant rights to grow taro. When taken into account, those lands would require 2.9 to 8.8 mgd of water, based on Reppun’s recommended water budget.

MTF’s Hall also claimed that Miike ignored valid water claims by residents of the Hanehoi watershed. With regard to farmers Ernest Schupp, Solomon Lee, and Neola Caveny who together possess lots with appurtenant and/or riparian rights totaling 6.2 acres, Miike erroneously stated their acreage as 2.3 total acres, Hall argued.

Hall went on to say that Miike also failed to factor into his IIFS the domestic water needs of Hanehoi residents. The licenses, and also the subsequent revocable permits, under which A&B diverts East Maui streams included clauses protecting the water rights of native tenants for domestic use, Hall stated.

“There is no evidentiary support for the report’s refusal to allocate the additional water needed for domestic purposes by the Huelo community,” which includes as many as 100 people, he wrote.

The fact that all water not required by the IIFS to remain in the stream would be diverted by EMI’s ditches and not kept in the streams or shared with riparian and appurtenant users “is inconsistent with the public trust doctrine,” he added.

Finally, Hall stressed the need for measures to be put in place to ensure that the amended IIFS are complied with. He cited the fact that neither Schupp nor Caveny received the stream water allocations the Water Commission decided years ago they should get.

“Without these measures, or measures like them, it is likely that the amended IIFS will be illusory once again, no matter how often and how much downstream users complain about the continued violation of their protected rights,” Hall wrote before asking that the commission provide immediate interim relief for Schupp and Caveny by granting them the flows Miike recommended for Hanehoi and Puolua streams.

“The deprivation has been for such a long time that this immediate relief is warranted, even though … those claiming allocations of water within the Hanehoi watershed were and are entitled to much more water,” he wrote.

— Teresa Dawson

Volume 26, Number 10 April 2016

Leave a Reply