Public Hearings to be Held

On Fee Hikes at Small Harbors

When it comes to the state’s small boat harbors, “It’s kind of a chicken and egg or cart and horse thing. We can’t repair these things without funding [and] these places need to be fixed up,” explained Finn McCall of the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Boating and Recreation (DOBOR) at the Board of Land and Natural Resources’ December 7 meeting.

DOBOR has proposed a host of administrative rule changes that will raise harbor fees high enough to cover repair and maintenance costs, and bring mooring fees up to fair market rates as required by the state Legislature.

The agency first brought its rule package to the board in October, seeking approval to take the changes out to public hearings. Division administrator Ed Underwood explained that the state Legislature had amended the boating statute to require all fees for mooring in harbors be set in accordance with an appraised market value.

But when DOBOR proposed to do exactly that, it did not go over well.

“We’ve been getting calls of how ridiculous it might be, a 300 percent or 500 percent [increase],” said Maui Land Board member Jimmy Gomes.

Stanley Roehrig, a board member from Hawaii island, added that he knew someone with a berth whose fee would go from $74.16/month to $180/month under DOBOR’s proposed rules. “He’s in his early 70s. A 245 percent increase. He’s probably going to take his boat out of the water. … I know a fair amount of these gentlemen. A lot of them are senior citizens … tinkering on their boat. These are makule (elderly) guys and you’re going to raise their rate 300 to 500 percent. You guys are pupule (crazy),” he told Underwood.

Kauai board member Tommy Oi was less sympathetic. “You gotta realize, when you have a boat in a slip, it’s a privilege. Like an airplane at an airport. It’s not something that you’re supposed to have. You have it because you want to have it. … Even the boaters forget that. If you don’t want [to pay] move out and let someone else get in there,” he said.

Roehrig said that was a hard message to send to senior citizens.

Underwood explained that the fee hikes in general are intended to get the division to the point to where it at least breaks even. “By 2019, we are $875,000 in the negative,” he said, adding that DOBOR could spend the additional money from the new fees to tackle its $300 million worth of deferred maintenance. Some of DOBORs fees haven’t been touched since 1994, he noted later.

At that October meeting, the board held off a vote on sending the rule package to public hearings, instead asking DOBOR for more details on its expenses, revenues, and repair costs. When the matter returned to the board in December, Roehrig questioned the logic behind charging more money for dilapidated or vandalized facilities. “You want to raise the rates for electricity. No more electricity,” he said of one harbor that had its power system vandalized.

Similar to what McCall told the board, Land Board chair Suzanne Case said the board members were pointing out the department’s dilemma. “We have fees that haven’t been raised in a long time … It is a chicken and egg thing,” she said.

Whether or not board members think the fee increases are fair or justified, they may not have much, if any, discretion to fiddle with DOBOR’s recommended mooring fees, since they were based on the appraisal, member Chris Yuen argued.

“The law says we set the fees based on the appraisal. If the appraisal is $11 a foot a month, that’s what the fee is supposed to be,” he said.

While Roehrig didn’t disagree, he took issue with how the appraisal was done. He cited the appraisal, which stated that it “employed the hypothetical condition that the facilities are usable for their intended purpose although our site visit revealed catwalks under repair or construction, condemned or unusable.”

During public testimony, boat owner Randy Cates argued that if DOBOR raised its fees as proposed, it would eliminate a lot of commercial fishermen and affect local seafood production, especially on the outer islands.

“You’ll get yachts that sit [and are] used a few times a year, rather than the fishermen that catch fish that goes into the restaurants,” he said. (One of DOBOR’s more controversial proposals is to base mooring fees on slip length, rather than vessel length, which some have argued puts small boat owners at a disadvantage.)

Cates added that about 95 percent of Heeia Kea small boat harbor is used by commercial tour boats, which can carry 1,200 passengers per day. He said commercial operators charge $140 for a four-hour tour, on the low end. If DOBOR decided to charge them $3-5 a person to land at the harbor, that would generate $1.2 million, he said.

Currently, DOBOR gets only 38 cents per person. “What the boating division is receiving from this large impact of tourism is out of balance. …They overwhelm the harbor. We can’t get a parking space,” he said.

When asked by Yuen how he arrived at the 38 cent figure, Cates said he took the daily amount of allowable passengers, 800, assumed operations during six days a week and “just divided it. Quick math.”

Cates also complained that the commercial operators charge their customers a transportation fee from the hotel to the harbor and a smaller fee from the Kaneohe Bay sandbar to the harbor. DOBOR only gets the small fee. “It’s unfair. Boating division knows it’s not fair,” he said.

Case said she was aware of the practice and added, “we are looking into it.”

Board member Sam Gon moved to approve the request to take the rules to public hearings, which he said was one of the best ways to explore the points that had been raised.

Referring to critical news stories in recent years alleging severe under-charging of lessees and permittees by the department, Oi added, “now it’s time to put up or shut up.”

While the way the money would be spent was not part of the rule package, board member Keone Downing said he had a problem with the fact that boating fees from individual harbors go into a general DOBOR fund and not back into that harbor. If there’s a way to start looking at ensuring that funds generated by a harbor goes to improving that harbor, “then excess can go to others … then I can stand behind raising fees,” he said.

Board members Gomes and Roehrig said they thought the proposed increases were simply too high. “You have commercial fishermen that’s going to be by the wayside,” Gomes said.

“I would defer this until we can tailor [fees] to the various facilities around the state and focus on protecting our local fishermen,” Roehrig added.

Yuen, however, again referred back to the legislative directive. “Sometimes the Legislature tells us what to do and we have to do it. I think the Legislature told us appraise what these slips are worth and charge the people what the appraisal says. … I think we can phase it in over a reasonable time period [but] we’re not supposed to decide that, nah, we think this is a little too much for the people to bear. If it’s too much, we’re not going to fill the harbors,” he said.

In the end, the board approved Gon’s motion, although Roehrig and Gomes opposed it.

Four Areas Opened

To ‘Deep 7’ Fishing

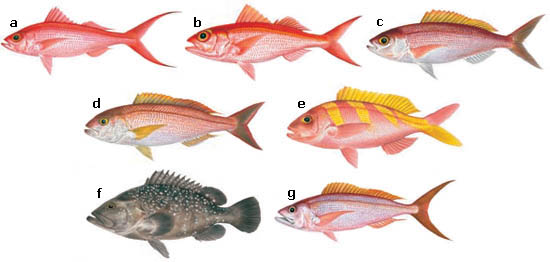

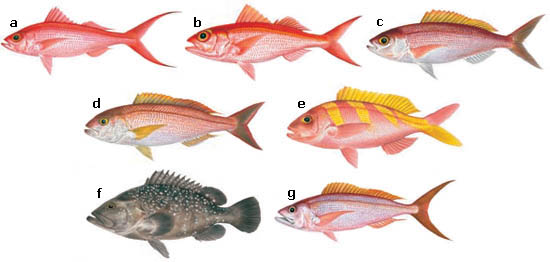

The Board of Land and Natural Resources voted on January 11 to open up to bottomfish fishing four of its 12 bottomfish restricted fishing areas (BRFAs). A 2018 stock assessment of the seven main targeted bottomfish species by the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center found that the stocks were neither overfished nor subject to overfishing.

That was not the case a decade ago, when stock assessments suggested that some species of bottomfish were highly imperiled. In response, the Land Board voted to establish 19 BRFAs around the Main Hawaiian Islands.

In addition to the state’s actions, the National Marine Fisheries Service later began setting annual catch limits (ACL) based on recommendations from the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council (Wespac). The council has set the current limit at 492,000 pounds – up from 306,000 – at a point where scientists predict there is a 42 percent chance that, if the limit is reached, the stocks would be subject to overfishing.

The council and bottomfish fishers have argued for years that the state should abolish all of its BRFAs because they believe NMFS’s ACL provides sufficient protection of the stock.

In light of the new stock assessment, the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) recommended that the board open four of the 12 remaining BRFAs — those off Poipu, Kauai; Penguin Banks south of Molokai; Hana, Maui; and Leleiwi, Hawaii Island.

So why four and not all?

Some people are uncomfortable with the ACL being set at a 42 percent risk of overfishing, DAR’s Ryan Okano told the board. Also, the division lacks data on non-commercial take, which some estimate is as high as commercial take, he said.

“To the extent the concept is that it [the BRFA system] has been contributing to the recovery, you want to be careful about it and you want to monitor it,” added Land Board chair and DLNR director Suzanne Case.

Retired DAR biologist Alton Miyasaka, however, testified in favor of opening all of the BRFAs. All the science indicates the bottomfish stock is doing well and the BRFAs are merely a holdover from a time before joint federal and state regulation, he said, adding, “That time has passed. … The BRFAs themselves have outlived their usefulness.”

Several members of the public, many of them commercial bottomfish fishers, echoed Miyasaka’s sentiments.

Fisherman Roy Morioka suggested that it was highly unlikely that the commercial catch this year would come anywhere near the ACL, since the fishery was well into the 2018-2019 season (which started in September) and had only caught around 15 percent of its 492,000-pound limit. “We’re not gonna get even close. The governing factor primarily is weather,” he said.

He added that by keeping the BRFAs, the state was killing the bottomfish fishery, because they force vessels to travel farther out to sea to catch fish. A small-boat guy would never be able to travel 20 to 30 miles to reach some of the good fishing banks, he explained.

With regard to concerns that a 42 percent risk of overfishing might be too high, Wespac’s Marlowe Sabater pointed out that the process by which the ACL is determined includes buffers and accounts for scientific and management uncertainty.

Even so, Case pointed to a 2014 paper on University of Hawaii scientist Jeff Drazen’s evaluation of the effectiveness of BRFAs, which “repeatedly suggests BRFAs have positive effects. This is why I’m uncomfortable with the recommendation to open up all of them,” she said.

Sabater said that Drazen’s work had been reviewed by Wespac’s Scientific and Statistical Committee, which concluded that there wasn’t enough baseline data in that study to justify a conclusion that BRFAs have positive effects.

“So there’s uncertainty either way,” Case said.

“I’m saying the uncertainty … has all been accounted for,” Sabater replied.

Land Board member Chris Yuen suggested that the question of the effectiveness of BRFAs could be answered by beginning a study now of the remaining ones.

Sabater agreed that was possible. DAR planned to increase the resolution of its monitoring grids, which would provide higher resolution data to set up a baseline, he said.

Yuen made a motion to approve DAR’s recommendation to open only four. However, he added, “I’m not wedded to keeping the others. This issue should be re-examined at some point.” He recommended that DAR report back in three years, which is when an updated stock assessment is expected to be issued. At that time, the board would consider any recommendation DAR had regarding the other BRFAs.

The board unanimously approved the motion.

Kaneohe Yacht Club

Keeps Permit, For Now

The Kaneohe Yacht Club (KYC) in Windward Oahu has been operating for nearly a century, and in that time, its members have had the exclusive use of the piers it has built on state submerged land. That may soon change, depending on the type of long-term disposition the Board of Land and Natural Resources ultimately approves for the club’s improvements.

At the board’s January 11 meeting, the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Land Division proposed canceling the club’s month-to-month revocable permit for recreational boat pier purposes, which had been annually renewed since 1977 with the same rental amount of $177.89 a month until 2016. That year, the Land Board raised the rent by 1.5 percent to $183.23 a month.

In 2016, a revocable permit task force identified the club’s permit as one that should be converted to a long-term disposition, such as a lease or easement. Easements for encroachments on state submerged lands are typically non-exclusive, meaning that the public is allowed onto any private improvements within the covered area.

While yacht club representatives expressed concern about this condition, the Land Division recommended that the Land Board convert the club’s permit to such an easement anyway. “If KYC chose not to convert the RP into a long-term disposition, staff would have to recommend the board terminate RP 5407 and demand KYC remove all improvements on state lands,” a staff report stated.

The report also noted that the area covered by the permit, 8,014 square feet, is, inexplicably, nowhere near the total area being used, and the club appears to have also made a number of unauthorized improvements, including two finger piers, a boat ramp, a floating pier, and a walking plank. Based on a November 2018 inspection, the division estimates that the various authorized and unauthorized improvements cover about 21,000 square feet.

The division recommended the issuance of a 55-year easement. The division would require a one-time payment, the amount of which would be determined by an appraisal of fair market value.

Until the easement was finalized, the permit would continue at an increased rent of $1,000 a month or 10 percent of gross revenues from the land, whichever is greater, starting March 1.

Board member Keone Downing suggested that the division require more than just one payment for the easement, since the club’s slip fees will probably change over time.

Land Division administrator Russell Tsuji said that for leases, rent adjustments are normally done after 10 years.

Board member Tommy Oi asked why the permit was never turned over to the DLNR’s Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation (DOBOR).

“Because it’s not a public harbor. … It’s submerged lands,” replied board chair and DLNR director Suzanne Case.

“‘Cause we get everything nobody wants,” Tsuji added, which drew a lot of laughs.

Years ago, the department legitimized a slew of private, illegal piers scattered across Kaneohe Bay through a limited amnesty program. The yacht club, however, failed to take advantage of it before the program ended, land agent Barry Cheung told the board.

Board member Stanley Roehrig took issue with the division’s apparent willingness to forgo the rent lost due to failures over the years to make sure the permit reflected the actual area being used. The pier had been extended repeatedly, but “you folks never collected any money from that. They were charging people, they were collecting money,” he told Tsuji.

Tsuji replied that his division wasn’t involved in any expansion of the area used, but the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands was. Conservation District Use Permits were issued for some of the work.

“Nobody collected the money for using the water area for all these years. How could it slip through the cracks? Nobody caught it until now,” Roehrig complained.

“They raised the rent in 2016,” Case noted.

“Excuse me, 2016 … 29 years we never collect money. So what are we gonna do? We just waive it?”

Case pointed out that the division never charged the club and said the thing to do was simply charge fair market going forward.

“Arguably, the yacht club could say we waived [the rent],” Tsuji said.

Board member Chris Yuen estimated that the division probably didn’t lose out on that much rent, maybe $10 a month.

“A more basic question: What are we calling the easement area? Is it just the piers and catwalks or does it include the area that’s shaded by the boats?” Yuen asked.

Cheung replied that leases or easements for a dock or pier are usually confined to the footprint.

“You raise a good question. We don’t have anything in the entire state of Hawaii like this and maybe it should be under DOBOR,” Tsuji said.

Yuen did not comment on that, but said that the state does charge boats to moor.

“If these boats, if they were moored in the ocean in a harbor, the state would charge them a fee. It wouldn’t be the value of the block that got dropped into the ocean,” he said, adding that he wasn’t sure basing the rent on the pier’s footprint was a valid approach.

Board member Downing also pointed out that the club doesn’t just control what happens on the piers, but also uses the water between the piers where the boats maneuver. “Maybe they let the public come in. I’d like to talk to the yacht club. … We gotta be careful what we ask the appraiser to appraise,” he said.

Case said she thought the board should defer the matter, given all the questions board members raised, and KYC commodore Frederic Berg agreed.

“We probably should step back,” he said.

While some board members were looking to treat the club’s facilities like those at a public boat harbor, he said, “I look at it as just another pier in Kaneohe Bay, like the private piers. … Much like a homeowner who has a pier in front of their house, we have a pier in front of the club. … We don’t make a profit. We set the rates to recover the costs. … Some of us live on the bay. The yacht club is our access.”

Board member Oi asked whether the club would be agreeable to transferring jurisdiction from the Land Division to DOBOR.

“I have no idea of what the impacts would be,” Berg replied.

Referring back to what Land Division proposed, Downing asked, “Can the public walk on there and go fishing?”

Berg said he wasn’t sure whether the revocable permit allows that, but any boat that needs help or assistance they would have safe harbor, even if they were non-members.

Downing repeated, “Can the public go onto the pier and fish?”

Tsuji reminded Berg and the board that the easement being proposed was for non-exclusive use.

“Are you clear that’s what’s being proposed?” Case asked Berg.

“Yes,” he replied.

The board then voted to increase the permit rent and require the submission of a statement of gross monthly revenues. It deferred action on the easement.

— Teresa Dawson

Leave a Reply