‘Dormant’ vs. ‘Closed’

Jim Cook, a former Wespac chair and NWHI lobster fishing permit holder, told Environment Hawai`i that he believed the lobster permit holders hoped the fishery would eventually resume. “Certainly we did,” he said. “I would say that until the final sanctuary designation, we hoped it could be reopened.”

When President Bush issued his proclamation for the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument in June 2006, he maintained the status quo for the lobster fishery by again capping harvests at zero. In addition, the monument required all commercial bottomfish and pelagic fishing in NWHI waters to cease on June 15, 2011. This time, NMFS accepted the lobster harvest cap as final and stopped announcing any intention to continue research to direct future management for that fishery.

Economic Impact

Before Bush created the monument, NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program was in the process of designating the NWHI reserve as a national marine sanctuary. And in its 2004 proposed fishing regulations for the sanctuary (which favored keeping the lobster fishery closed), it concluded, “The economic impact to this [lobster] fishery occurred when the fishery was closed in 2000 by both NOAA Fisheries and through a federal court order. Maintaining a closure of this fishery will not create significant additional economic impact because it is not currently in operation and catch declined by 90 percent while the fishery was open – fluctuating dramatically as it dropped. This variability, and ultimately the decline in catch, led to an overall economic decline in the fishery from its height in the 1980s until it closed in 2000. Recent research indicates a small level of population building may be taking place, but likely not enough to support a substantial fishery.”

Two months before Bush issued the proclamation, Wespac council members debated the issue of compensation to NWHI commercial fishermen. While the council as a whole favored compensation to those who would be affected by a sanctuary designation, some members felt the lobster fishermen would not be economically impacted and should not receive any compensation.

Then-Wespac chairman Sean Martin, however, argued at the council’s April 2006 meeting that despite the indefinite closure, the NWHI lobster fishery was “an existing fishery” that could be reopened under the right conditions.

Hawai`i’s congressional leadership sided with Martin’s point of view. A little more than a year after Bush established the monument, he signed the 2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included an earmark inserted by Daniel Inouye, senior senator for Hawai`i, that directed the Secretary of Commerce to create a “voluntary capacity reduction program” for fishermen holding NWHI commercial fishing permits to catch either lobster or bottomfish. The program would compensate participants for “no more than the economic value of their permits” and also provide for an optional vessel and gear buyout.

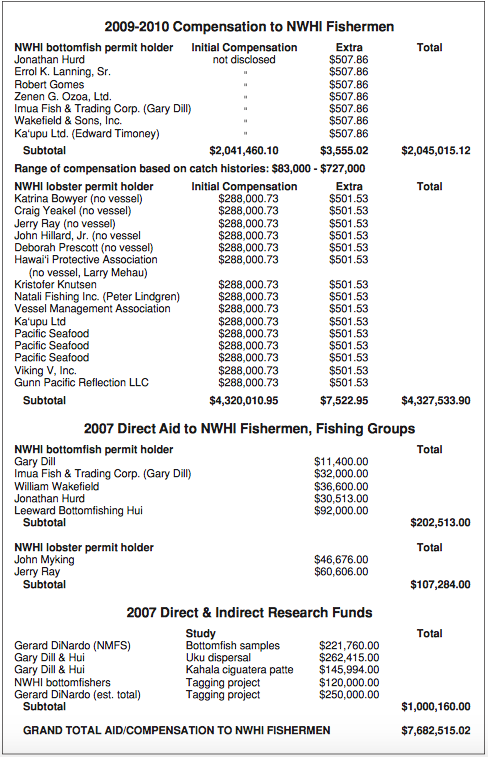

The act ignored the fact that lobster fishing permit holders already had an opportunity in 2005 to seek compensation for their ouster from the NWHI. And two of them – John Myking and Jerry Ray – received a total of $107,284 in fisheries disaster relief as part of a $5 million federal grant to Hawai`i longliners and NWHI bottomfish and lobster fishers affected by federal closures. (The longliners received the bulk of that grant, which served mainly to reimburse them for legal fees. It also provided hundreds of thousands of dollars to NWHI bottomfish fishermen.)

The language limiting compensation to the “economic value” of permits did not completely escape notice and, in fact, raised concern among some NWHI fishermen. Assigning an economic value to either the bottomfish or lobster permits would require some creativity, given that the bottomfish permits were non-transferable, that the lobster fishery effectively shut down in 2000, and that all commercial fishing would end in a few years. Recognizing the possibility that NWHI permit holders could receive little or nothing given a strict reading of the act, Cook, who is also Martin’s business partner, urged NMFS in 2008 to be flexible in its determination of economic value.

And it was. Because the act identified both bottomfish and lobster fishers as eligible for compensation, the agency proceeded as though the monument’s designation actually had an economic impact on the lobster fishers.

When asked whether there were any discussions about how or why a capacity reduction program should apply to a group of fishers who aren’t allowed to catch anything, NMFS fishery policy analyst Toby Wood (who was assigned to oversee the program after it had been established) said that none had occurred as far as he knew. Because the appropriation specifically identifies lobster and bottomfish permittees, “we were caught with having to be equitable to both,” he said.

In the May 2009 issue of MPA News, Wood explained, “While the lobster fishermen have been held to a zero-harvest guideline in the NWHI since 2000, the permits still exist….The potential of re-opening the NWHI lobster fishery has continued to be the hope of many fishermen who still hold their permits.”

In April 2009, NMFS published its proposed rules for the compensation, and, for the most part, both the lobster and bottomfish fishermen argued for more money and/or the most favorable and fair evaluation terms. Wood told Environment Hawai`i that some bottomfishermen wanted more than $1 million for their permits. While the lobster permit holders encouraged NMFS to consider their best catch years in determining the economic value of their permits, Jay Nelson of the Pew Environment Group opposed giving anything to the lobster fishermen, telling MPA News last year, “Almost a decade after the lobster stocks collapsed, and in light of the absence of their recovery, it would be hard to argue that the remaining lobster permit holders deserve compensation as a consequence of the monument designation.”

Creative Accounting

In September 2009, NMFS published its final rules for the compensation program, which were basically identical to the proposed rules. Without an active market for the permits, NMFS determined their economic value by taking the Net Present Value (NPV) of documented net revenues in order to calculate lost investments and future earnings. NMFS established a base value using the three consecutive years in which each fishery actively operated immediately before the monument designation. For the bottomfish fishery, those were 2003-2005; for the lobster fishery, they were 1997-1999.

“These time periods are different for each fishery in recognition of different operational and historical circumstances of each fishery,” NMFS stated in its April 2009 Federal Register notice on the proposed rules.

For the bottomfish fishing permit holders, the NPV of each permit reflects the gross revenues for 2003-2005 for each permit multiplied by approximately 2.5 to reflect the value of future earnings. According to Wood, NMFS relied on 2003 net revenue data from the NWHI bottomfishers; that was the most recent year for which his agency had solid cost-earnings, he said. NMFS then used the net-to-gross revenue ratio in order to derive the NPV using 2003-2005 sales revenues for each individual bottomfish permittee.

For the lobster permit holders, whose permits were transferable, NMFS found that determining the economic value was “problematic,” stating, “The NWHI lobster permit market is small, unmonitored, and has been largely inactive over the past eight years. In the later years of operation, the lobster fishery was undergoing operational changes including the formation of a cooperative to manage fishing capacity and costs, and to share revenue among permit holders. Also, some vessels were experimenting with higher value-added production methods to allow the export of live lobsters to Asian markets. All of these factors make it difficult to determine the economic value of each individual lobster permit.”

According to a 2003 Marine Resource Economics article by the University of Maine’s Ralph Townsend and NMFS’s Samuel Pooley and Raymond Clarke, the existing 15 lobster permits were excessive given the NWHI stock conditions of the 1990s, which have not recovered much since then. In fact, in the last three years of the fishery, most of the permits went unused. In 1997, only nine lobster permittees fished the NWHI. In 1998, 14 of the 15 permit holders (often referred to as the “NWHI lobster hui”) agreed that only four of them would fish that season, while the rest would receive a percentage of their revenue. Five vessels (the four plus one non-hui vessel) fished that year, but that agreement quickly fell apart, and in 1999, six vessels fished the NWHI.

To simplify things – regardless of whether or not a permit-holder had fished, lost money, or even had a vessel anymore – NMFS calculated a net revenue value for the fleet as a whole, applying the same net-to-gross revenue ratio used for the bottomfish permittees to the average gross lobster revenues for 1997-1999.

Swift Action

To administer the capacity reduction program, NMFS hired the Oregon-based Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission (PSMFC). In October, PSMFC finance officer Pam Kahut wrote to the remaining seven bottomfish and 15 lobster permittees informing them of the program and sending each a proposed compensation amount. All permittees had to respond before any funds were disbursed, and once they received compensation, their permits would become invalid. Bottomfish permit holders who rejected compensation would be allowed to fish until June 15, 2011.

The permit holders responded quickly, and by November 23, Kahut had mailed confirmation letters to all of the permittees, notifying them that they could choose to receive their payments in either December 2009 or January 2010.

The 15 lobster permit holders each received a check for $288,000.73, for a total of $4,320,010.95. Because confidential catch data from individual fishermen had been used in the calculations for the bottomfish fishers, NMFS chose not to disclose the amounts each of the seven permittees received. Although eight would have been eligible, one permittee died before receiving compensation. As a group, the bottomfish permit holders received $2,041,460.11, and individually received payments ranging from $83,000 to $727,000.

On January 21, NMFS issued a press release announcing that it had completed the NWHI lobster and bottomfish fishermen compensation program.

“[B]eginning in January 2010, the commercial fisheries for bottomfish and lobsters are permanently closed in the Monument,” it stated.

According to emails from NMFS, overhead costs totaled $324,951, leaving $11,078 unspent. In early February, Kahut distributed this among the aid recipients, sending a second check for a little over $500 to each permittee. Although NMFS’s final rule states that any leftover money would be put toward a vessel and gear buyout, Wood said it wasn’t enough for such a program. NMFS chose to distribute the money to the fishermen instead because, Wood said, “Basically, it was their money.” He added that the true value of the permits was “way over what was allocated.”

In the end, Cook said he thought the amounts the lobster permittees received was adequate and fair. As for those who’ve dismissed the idea of compensating them given the state of the NWHI lobster stocks, Cook said those arguments are, “par for the course for Jay [Nelson] and the sanctuary program.” He also alluded to research that has attributed the stock decline mainly to an unpredicted change in climatic conditions that affected spiny lobster larvae dispersal. Although the concurrent lobster fishing exacerbated the decline, Cook said the fishermen were merely “following the rules before them.”

* * *

The Council Votes on ’Customary Exchange’

At its March meeting in Guam, over the objections of Hawai`i council member Peter Young, the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council recommended that the Naitonal Marine Fisheries Service adopt rules that would allow communities to give fishermen fishing in the Marianas Trench and Pacific Remote Islands Areas Marine National Monuments money – or in Wespac’s words, “cost recovery through monetary reimbursements” – for fishing expenses, so long as that fishing is conducted for “cultural, social, or religious reasons.”

Wespac defined the practice as a “customary exchange,” attempting to distinguish it from commercial fishing (which is prohibited in both monuments) by emphasizing that it is a “non-market exchange of marine resources between fishers and community residents for goods, services and/or social support…”

For Further Reading

Environment Hawai`i has published several articles giving more background on this topic.

Leave a Reply